Henri Matisse, Nature mortre aux oranges, 1912. Images: Supplied.

There’s always more to art than the painting on the wall. And if you bring together genius, towering ego and social tumult, the results will be both volatile and spectacular.

The story of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, their friendship and their intense rivalry, is at the heart of the National Gallery of Australia’s summer exhibition, open now.

https://www.facebook.com/riotactnews/videos/801799360241573/

Matisse was at the height of his powers as the great innovator of colour and line when a young Picasso appeared in a blaze on the creative horizon, full of energy that curator Jane Kinsman calls “unstoppable and untameable”. Together, as NGA director Nick Mitzevitch says, their influence shaped much of the 20th century’s art.

Still life [Nature mort], 1924, Pablo Picasso.

“The relationship was very complex. Matisse was really unhappy that he was about to take the mantle of the most radical fabulous artist of the Fauves and then Picasso produces this revolutionary work that Matisse scornfully called ‘the little cubes’.

“But then they started looking at each other’s work very carefully and that’s been the most interesting part of the journey for me, using works that have never been seen together before.”

Curator Jane Kinsman and Musee Picasso director, Laurent le Bon. Photo: Supplied.

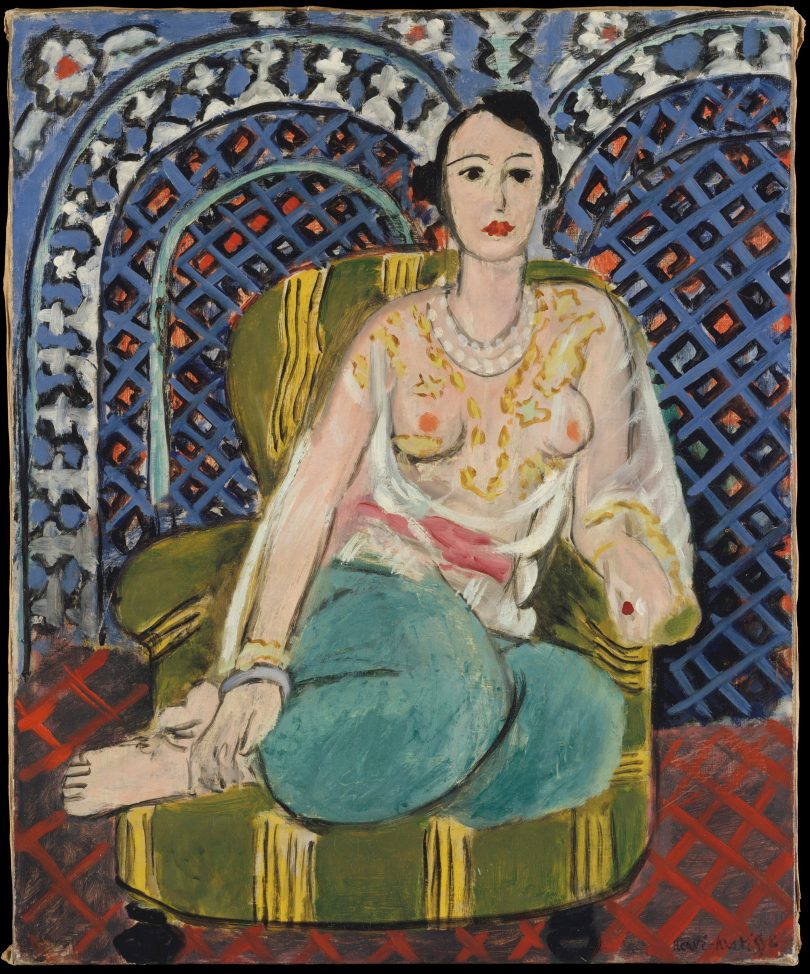

One of those pairings is between Matisse’s odalisques, represented by two works on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and Picasso’s large Nude on a Red Chair 1929, from the Musee Picasso, Paris.

The Matisse works are fresh, lush and sexy. The patterns and colours are vibrant, informed by Matisse’s longstanding love of Islamic textiles and the Western obsession with the mysterious, exotic and erotic East. The vivid image would have been startlingly informal for viewers in 1926 but is essentially, as Kinsman says, “comfortable to the eye”.

The Picasso is more like a slap in the face. It’s huge and filled with visceral energy, jagged emotion and raw, shouting colour. The subject is Olga Kohklova, a Russian dancer who was Picasso’s first wife.

Pablo Picasso, La lecture, 1932.

“It’s vile, quite cruel,” says Kinsman. “We have another etching of Olga and she looks like a screaming hyena. Picasso’s odalisque is a steal from Matisse, an image of his wife, and it’s not nice at all.”

Picasso readily described himself as a thief, a magpie who would steal from any source. But he also said that nobody looked at Matisse’s art like he did, and that “if I were not making the paintings I make, I would paint like Matisse”.

The competitive urges turned to admiration, and eventually to an intimate friendship.

When Matisse, the older by more than a decade, died, Picasso responded with a complex blend of angst and creativity. Likely challenged by his own mortality, he at first cruelly ignored the family of his old colleague, then responded with a series of lively, richly patterned and coloured works. The Studio, from 1955, is clearly inspired by Matisse’s love of rich colour and pattern making.

Kinsman’s gift in this exhibition has been to weave those intense personal stories together through sculptures, drawings, costumes and paintings. The hugely dramatic Ballet Russe costumes are here from the NGA’s own collection, as is Picasso’s Vollard Suite.

Henri Matisse, Seated odalisque, 1926.

The Musee Picasso is a major lender and from there, we see works from both artists including the lush and lively Matisse Still Life with Oranges and the major Picasso works, including Reading from 1932. Three of these masterworks have never before been seen in the Southern Hemisphere.

There are 200 works in the exhibition, sourced by Kinsman over three years from 22 public and private collections around the world as well as the NGA’s own collection. It’s her last major show as the head of international art; she will become the Gallery’s first emeritus curator.

NGA director Nick Mitzevitch paid tribute to Kinsman, noting that she had built on the visionary foundations established by James Mollison by adding significantly to the NGA’s holdings of both Matisse and Picasso.

As Laurent le Bon, director of the Musee Picasso said to loud cheers at the opening, “Vive Canberra, Vive Picasso, Vive Matisse!”

Matisse & Picasso is at the National Gallery until 13 April 2020.

Original Article published by Genevieve Jacobs on The RiotACT.