Mark Feeney with a Mountain Pygmy Possum. Image by Mel Schroder

Mark Feeney has a job that any self-respecting snowsportsy scientist would die for. He is the Environment Officer at the Perisher Ski Resort in South East NSW.

Mark helps connect the Resort with the National Parks and Wildlife, as well as overseeing kids’ environmental programs, and scouting for a wonderfully cute and highly endangered species.

I met Mark at the Sundeck Hotel in Perisher.

The Perisher community is small and supportive, all about good mates and lots of fun times.

Some odd traditions emerge, the Sundeck Hotel serves the best cheap lunch on the slopes with their daily kransky barbecue (including the infamous jalapeno-laden Snow Dog), but of an evening you’re able to buy an entire rack of test tubes, each holding a different kind of schnapps.

I’m always on the lookout for kitschy scienceness!

Either way, Mark’s got a good gig. So how did he get to be there?

Mark’s interest in science was first sparked in geography class, learning about how humans and ecosystems interact.

After finishing high school he worked as an outdoor education instructor in Southeast Queensland, camping most nights of the week with co-workers whose high moral codes and environmental awareness inspired him to study environmental science at uni.

A life-changing moment came when he worked in the Pilbara, Western Australia, with indigenous rangers.

“It was a short stint but it gave me a glimpse of the traditional knowledge the Martu people have and utilise in terms of land and ecosystem management,” he says.

“Prior to then I had minimal exposure to traditional land management techniques, and it made me realise how lacking my own knowledge is…it is certainly something that has stuck with me.”

So with such a strong appreciation for environmental codes, what’s it like working at a resort like Perisher?

“I acknowledge that landscape, country and ecosystems have a right to exist purely for their own existence, there does not need to be a benefit or purpose to people,” Mark explains.

“Having said that, I will be the first to enjoy these natural areas where a balance can be made between visitation or recreation and conservation.

“In my experience, when people can relate positive experiences to something I think they are more likely to advocate for it,” he says.

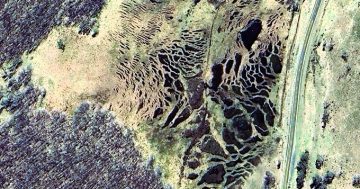

Sunrise over Perisher Resort. Image by Kate Burke

A positive experience for Mark came in the form of the beautiful, tiny, endangered marsupial known as the Mountain Pygmy Possum.

Since 1986, the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) has conducted annual surveys of Mountain Pygmy Possum populations across Kosciuszko National Park, including at one location inside the resort boundary at Blue Cow.

A glance at the Perisher trail map shows a gully on Mt Blue Cow as “area CLOSED for Mountain Pygmy Possum protection.”

These possums are the only animals in Australia that hibernate every winter.

They need to keep their body temperature regulated during their long sleep, and they use the snow for insulation.

Possums tend to move between boulder habitats, so they are vulnerable to interactions with people and feral animals. Climate change presents the greatest threat, with the snowline already retreating due to rising temperatures.

Their situation is desperate.

Thought to be extinct until the 1960s, the NSW population was estimated to be between 500 and 700 in the year 2000. By 2005 the population was thought to have fallen by a further 20% with a significant decline after the 2003 bushfires. By 2005 the population was thought to have fallen by a further 20%.

The Blue Cow subpopulation is particularly vulnerable, in 2008 only 6 possums were found at this location (although it’s thought twice that number may have been present). The situation has improved, with 45 possums trapped and tagged for identification in 2015, the highest number since 1997.

Having a dedicated advocate like Mark Feeney is helpful, he’s not just going through the motions.

“The Parks and Wildlife staff and volunteers involved in the surveys are passionate and have a wealth of knowledge,” he says.

“Being a part of the survey work is a real privilege, and doing this in a work capacity is something I day dreamed about as an undergraduate.”

Mountain Pygmy Possum. Image by Mel Schroder

I asked Mark how science has changed the way he relates to landscape and country.

“I (have) became far more aware on a personal level, of the impacts that my lifestyle choices are having on landscape and country.

“At the end of the day, until I am making good choices in all aspects of my life, it is unreasonable for me to have high expectations of others,” he believes.

“Often I find I have a greater sense of connection to natural landscapes and country then I do with built landscapes and large groups of people.

“I feel more content having a meal under the stars and going to sleep in a sleeping bag then I do having a meal at a pub or restaurant,” Mark says.

“If a few weeks goes by without having been camping I find I can get a bit stressed out.”

The balance between a big businesses like Perisher Resort and the delicate, local ecosystems that surround it is a precarious one.

Having an Environmental Officer who appreciates this country and its most vulnerable inhabitants can only be a step in the right direction.

Pic 1: Mark Feeney with a Mountain Pygmy Possum. Image by Mel Schroder

Pic 2: Sunrise over Perisher Resort. Image by Kate Burke

Pic 3: Mountain Pygmy Possum. Image by Mel Schroder