Warm summer nights, beach dreaming, magical skinny-dips in sparkling coastal lakes…and with every kick and splash, the dark water around us lights up like magic.

Many of us describe it as “phosphorescence”, but it is something more exciting than a mere glow – it is bioluminescence, evidence of tiny marine creatures and their remarkable way of shining a light on their predators.

Tonight, my man Pete and I are counting our lucky stars (figuratively – there are millions visible) as we leave the kids with Pete’s parents and head out in our little Investigator trailer sailer to spend the night by ourselves on Mallacoota Inlet.

Motoring through the narrow passage from Mallacoota Wharf to the main lake, red port markers blink to our left, green to our right, and up ahead the bright white beacon marking the channel entrance.

As we move away from the town, a waxing sliver moon sets behind the warm lights that glow from living-rooms and verandahs to the west.

The lake darkens, and as we set our sails and switch off the motor we are somehow sailing by the light of Venus and the Milky Way.

Even the tiniest light source suddenly seems alive, powerful, attractive.

The sky and the storms out on the far horizon are also alive. So alive that as we gaze at them as our keel runs aground on soft lake mud and we’re suddenly without steering. So alive that it happens again about ten minutes later. So alive that it takes us a good while to notice the bright green streams of water stretching out behind the rudder and fanning out like wings from the bow of the boat.

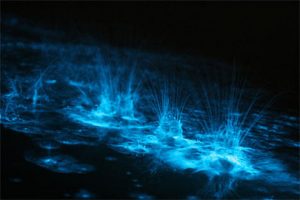

Bioluminescence at the Gippsland Lakes. By Phil Hart

Pete and I tied our boat up to a jetty in ‘The Narrows’. I dropped a rock in the water. Light spattered like sparks – at first on the surface, but then settling into a gentle twinkling that revealed a sparkle all through the water.

Stars twinkled above, and the lake was its own galaxy of billions of lights, off and on, tiny.

Then we saw the hive of fish activity along the shoreline. Flickering of tails, each movement trailing a shower of light. Splats and runnels of luminescence. All movements, the paths of all living lake life, traced in shining light.

Tiny plankton known as dinoflagellates, the food of many whales, emit light – not phosphorescence but rather bioluminescence – in a clever play, a kind of lure.

But why draw attention to yourself, little plankton? Why be a target?

It seems that it’s about a chain of events. Tiny plankton are hunted by predators such as crustaceans, and crustaceans are hunted by larger creatures such as big fish.

When crustaceans move to attack plankton, the plankton light up – “over here, over here!” – larger predators are attracted by the commotion and make a good feast of the crustaceans, effectively taking care of the plankton’s predators.

Dinoflagellates feed on algae and other plankton, and their populations can grow when there are high nutrient levels in coastal waters.

Bioluminescence is not limited to tiny organisms; in fact, there are bioluminescent species of sharks. And bioluminescence can hide some species instead of attracting attention (as described in the wonderful kids’ science book The Squid, the Vibrio & The Moon).

According to Ferris Jabr of Hakai Magazine, bioluminescent crustaceans called ostracods were dried for storage by Japanese navy personnel during the Second World War, then made into a paste and used as a covert light source for reading maps.

But here at Mallacoota, it’s the tiny plankton who are shining a light on their predators.

Pretty darn cool, sadly too cool for a midnight swim. Maybe another time.

All the same, Mallacoota Inlet is a stunning place to wake up.