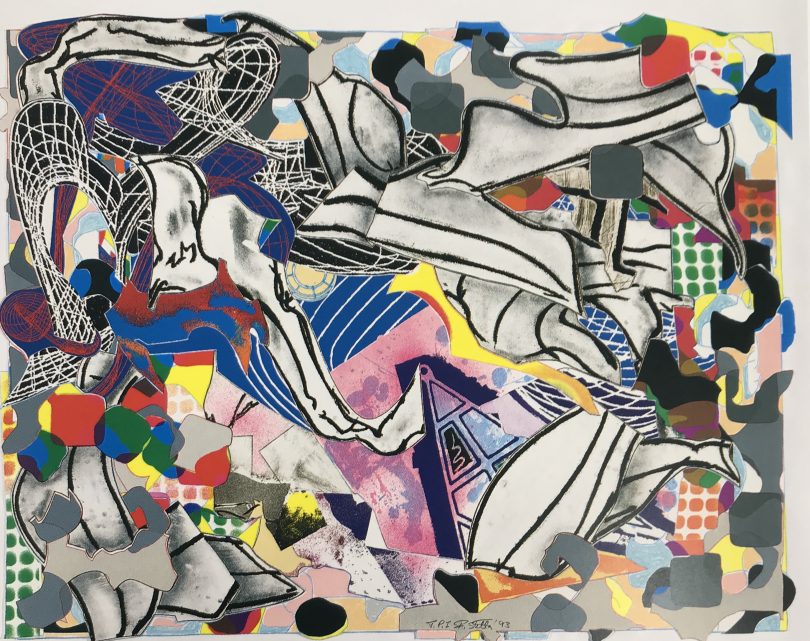

Frank Stella’s Ambergris from Moby Dick series forms a major part of the Lichtenstein to Warhol exhibition. Image: Supplied.

They’re a wild riot of colour, energy and form, and they’re part of an innovation revolution in art making. But the artworks in From Liechtenstein to Warhol, which opens this week at the National Gallery in Canberra, also tell a story about the Gallery’s inspired first director, James Mollison.

Forming a national collection in the 1970s, Mollison grasped the value of cutting-edge art that sat outside heavy gilt frames. “James Mollison understood American art and he didn’t go for the hierarchy that some directors valued,” says Jane Kinsman, head of international art and curator of the exhibition.

Exhibition curator Jane Kinsman at the launch of Lichtenstein to Warhol and the NGA in front of Jasper Johns’ Color Numeral series 1969. Photo: G Jacobs

The collection of prints began in 1973 when legendary Australian art historian Robert Hughes recommended that the NGA should acquire the Kenneth Tyler collection from the seminal printmaker, who’d sought collaborations with the highest-profile artists of the day.

Tyler was a technological innovator, who brought American industrial know-how to a European art form that had previously been artisanal and small scale. Curatorial assistant David Greenhalgh quotes the conversations that Tyler had with French printers who were still distilling herbs and using urine in the time-hallowed fashion of the past.

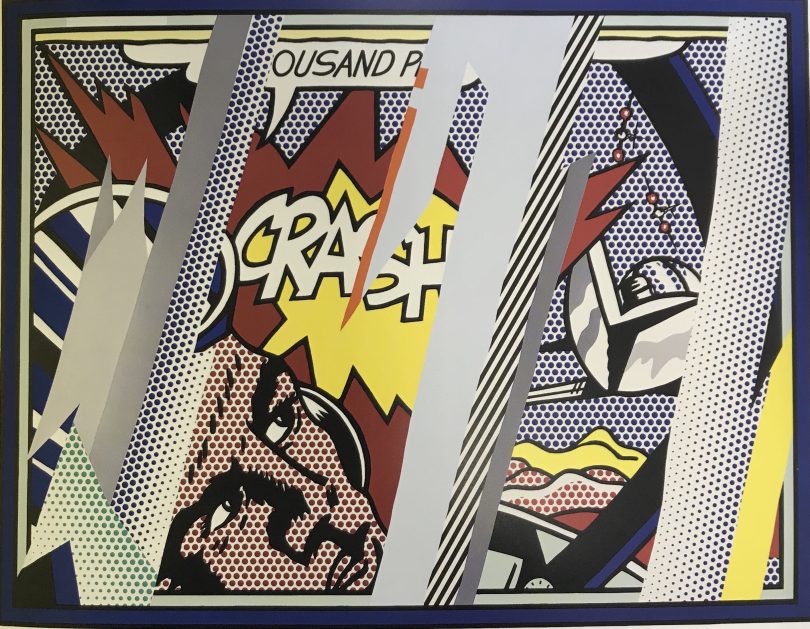

Roy Lichtenstein’s Reflections on Crash, acquired by the NGA from printmaker Ken Tyler. Image: Supplied.

“The American printmakers wanted to know what those chemicals actually were,” he says. “Ken Tyler is a technologist who reverse-engineers the process of making art. It’s artist-led but when he finds an area of experimentation, he asks who could I apply this to? Who could push their buttons as an artist, really stretch themselves?”

Those complex technological challenges were magnified because Tyler was working with some of the greatest (and sometimes most temperamental) postwar artists. Often they’d never made prints before and there was a fair degree of tension as Tyler pushed them to take creative risks.

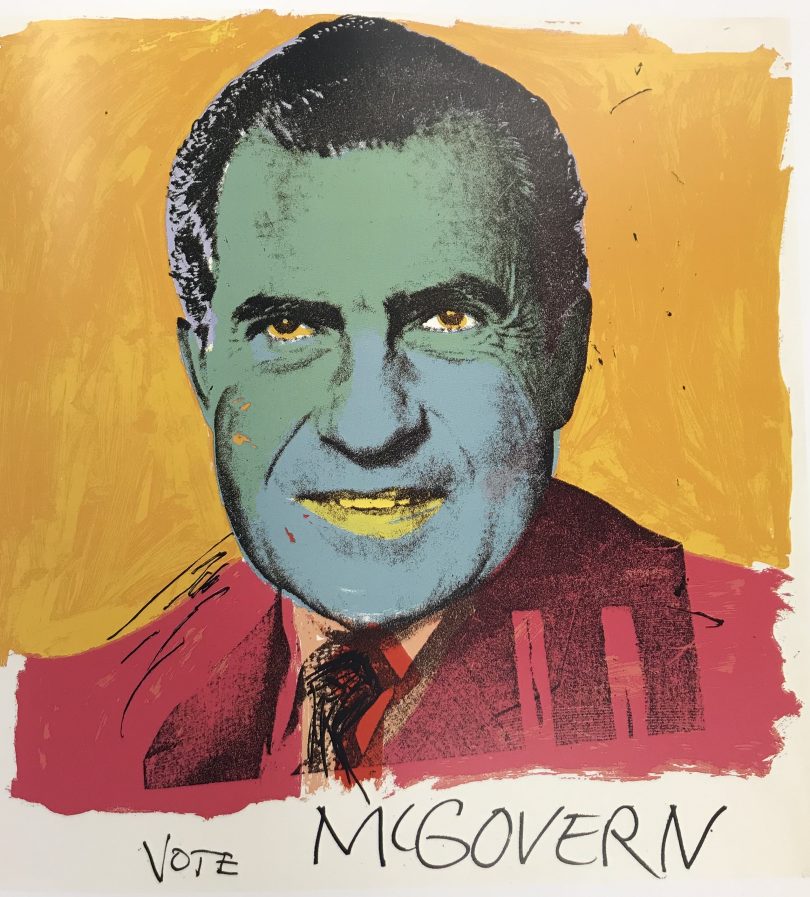

Andy Warhol’s print of Richard Nixon, Vote McGovern 1972 subverts the traditional election poster in content and form. Image: Supplied.

“Tyler worked with the artists at a scale that had not been achieved before in printmaking,” Greenhalgh says. “To do that you need paper that’s of the right size, so you need to learn how to create your own paper at a larger scale than has ever been produced before.

“You need to achieve the colour ranges that someone like Helen Frankenthaler uses which are stunning. But as an abstract expressionist, she’s used to working with paint, using soak stain techniques. How do you translate something so ephemeral and gestural into a woodblock to make prints?”

Frankenthaler is among several women artists in this show including Joan Mitchell, Anni Albers and Nancy Graves. They find a rightful place alongside better-known names including Andy Warhol, Robert Motherwell, Roy Lichtenstein and David Hockney.

The other significant thread in this story is the close relationship established by Jane Kinsman with Ken Tyler. After the initial 1973 acquisition, she met Tyler in 1985 and returned to the US where she purchased Roy Lichtenstein’s Reflections on Crash for the NGA. In 2002, the Tyler collection grew substantially when major works were gifted and acquired.

Kinsman thinks this collection exemplifies both the vision and insight of the NGA. She makes the point that the Tyler collection includes not just finished work but also the preparatory stages so that we can understand the underlying creative process for the artworks. Its breadth, as well as its depth, illustrates collaboration, technical achievement and artistic vision at a time of huge creative ferment.

That also makes the NGA’s Tyler collection an intrinsic part of postwar international art history. In 2012, Ken Tyler was awarded an honorary Order of Australia medal, one of just two Americans to have received the medal at that time. The award recognised his extraordinary generosity to this country, shared with all of us in this modest but important exhibition.

Lichtenstein to Warhol: The Kenneth Tyler Collection is on display at the National Gallery of Australia until March 9, 2020.

Original Article published by Genevieve Jacobs on The RiotACT.