Aunty Loretta Parsley unwraps a fence post split by Jimmy Governor, her great-grandfather. Photo: Supplied.

Jimmy Governor’s story has been told many times over the past 125 years, but never the way his great-granddaughter tells it.

The best-known account of Jimmy’s life and crimes is Thomas Keneally’s novel The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith. It was studied by a generation of Australian students and adapted into a film directed by Fred Schepisi.

Now Jimmy’s story has been told by his descendants and put in the context of the political and legal backdrop in the lead-up to Federation.

Walbunja knowledge holder and traditional custodian Aunty Loretta Parsley started researching the story of her great-grandfather almost 40 years ago, around the time of the bicentenary.

Years later, the Batemans Bay resident’s research led to a stage play by Clare Britton and the award-winning podcast The Last Outlaws by Katherine Biber, distinguished professor of law at UTS. Ms Biber’s subsequent book The Last Outlaws: The crimes of Jimmy and Joe Governor and the birth of modern Australia was published in July. It is dedicated to Aunty Loretta.

Wiradjuri/Wonnarua man Jimmy Governor married white woman Ethel Page in 1898.

In 1900 Jimmy was working for homesteaders, the Mawbey family. He cut trees to make fence posts for the property, helped by his brother Joe. Jimmy’s wife was taunted by the homesteaders for marrying an Aboriginal man and having a mixed-race child, Sidney.

John Mawbey rejected some of Jimmy and Joe’s posts and refused to pay their wages. With his wife being taunted, and unable to feed his family, Jimmy murdered some members of the family in July 1900.

“Jimmy went on the rampage and the police organised a posse,” Aunty Loretta said. “This was in the lead-up to the Federation when they were trying to establish the colonies and people were arguing in parliament about who should do the legislation.”

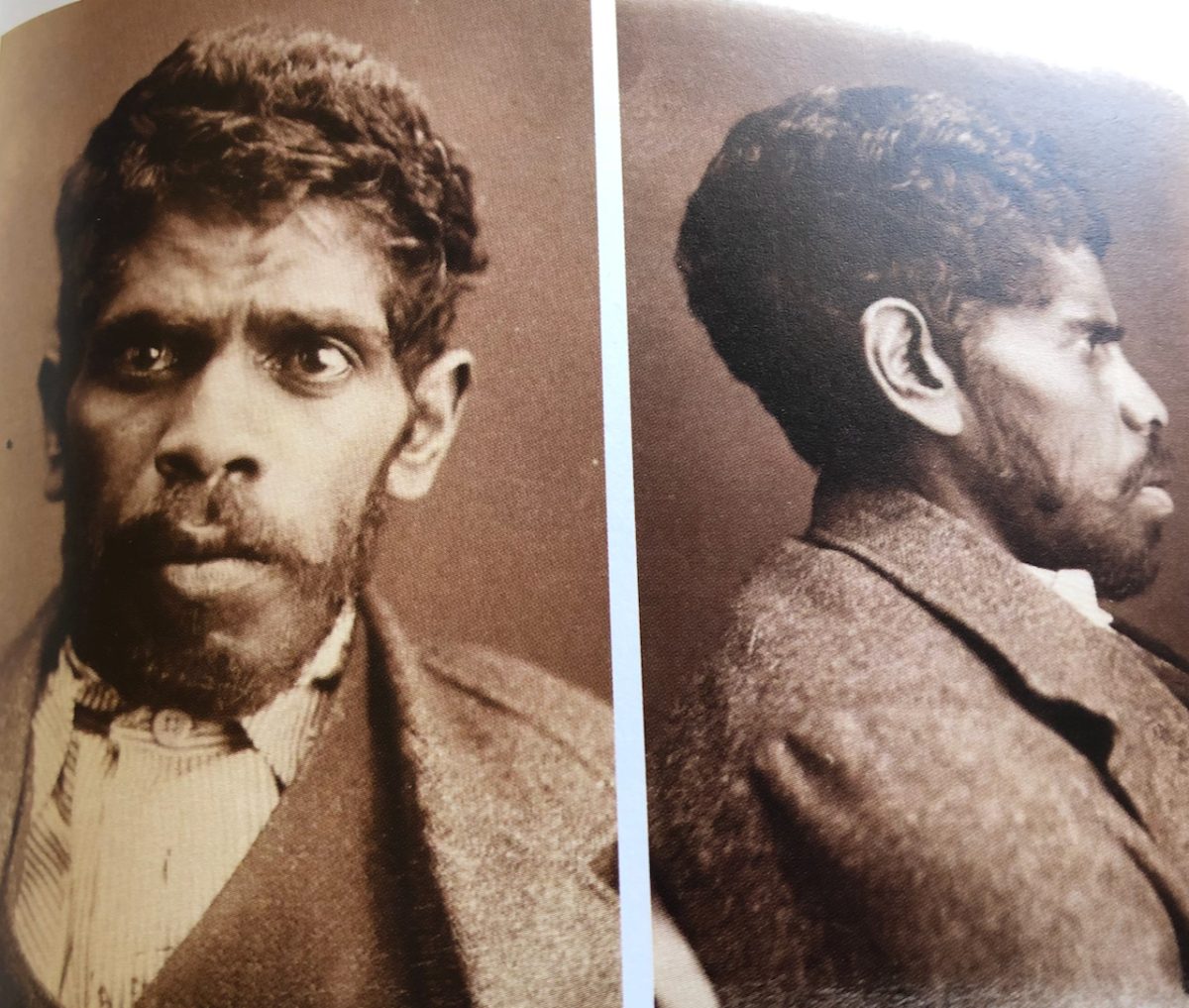

Jimmy Governor, photographed for his prison admission record. Photo: Supplied.

The authorities outlawed the two brothers. They eluded their captors for a long time using their bush skills.

Jimmy sent his wife and child to her family to protect them. Sidney’s surname was changed, and he was sent to live with another family for protection given Jimmy’s outlaw status.

After his capture, Ethel visited Jimmy in Darlinghurst Gaol. Because of their different races, the story gained notoriety in history.

Jimmy was tried and hung in January 1901. Ethel went to stay with her mother in Wollongong. Three months after Jimmy had been hung, Ethel gave birth to Thelma, Aunty Loretta’s grandmother.

Aunty Loretta’s father Cyril was 15 when he learnt that Jimmy Governor was his grandfather.

Wanting to know more about Jimmy’s story, Aunty Loretta and her husband took her parents to Gulgong where Jimmy had worked as a black tracker.

They put adverts in the newspaper appealing to people who knew of Jimmy. People replied saying that they knew him as a good person.

Being inquisitive, Aunty Loretta went on a journey of seeking out information, recording it and reflecting on why things had happened and was Jimmy a good person.

Jimmy’s story was gaining wider interest and was the subject of theses at universities.

Aunty Loretta Parsley (right) shows her painting of Jimmy Governor’s life, journey and family with podcast producer Kaitlyn Sawrey. Photo: Supplied.

Ms Britton, an artist/academic with a production company, approached Aunty Loretta.

“With Mum and Dad, we stopped at places significant to Jimmy and the production company presented it in Sydney’s Carriageway Theatre as a stage play, Posts in the Paddock,” Aunty Loretta said.

Next Ms Biber’s team wanted to do a podcast which won several awards. Ms Biber then wanted to write the book, but in context and with the family.

Having been on that journey so many years, Aunty Loretta said family history influenced relationships. Inevitably, there would be conflicts and cross-cultural interactions.

“For example, in the western world, the father is the head, so that would be Jimmy. In our world though the matriarch would be Ethel Page, but she is white,” Aunty Loretta said. “I have married a non-Koori man so in the western world he is the head, but I am Aboriginal and so I am the matriarch.”

She is navigating living in the white man’s world while holding onto her culture and beliefs.

Aunty Loretta has concluded that Jimmy was a good person who did a bad thing.

The book’s timing is right because “it is now truth-telling time in our history”.

“It is also about the political agenda and people climbing the ladder of power. You had Jimmy and Joe on the run, police hunting them down like savages, and politicians calling the shots.”