The War Memorial redevelopment site. Photo: Honest History.

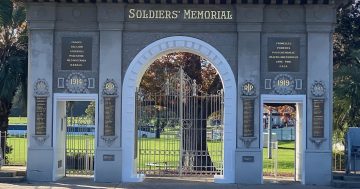

The Australian War Memorial marked its 80th anniversary yesterday as it embarks on the most significant change to the national institution in its history.

The $500 million redevelopment proposal has provoked controversy and bitter argument about the purpose and role of the Memorial.

For many, the key question is whether the Memorial is primarily a place of commemoration and reflection or is expanding into being a museum, something beyond its original charter.

The redevelopment, which will provide more space to tell the stories of more contemporary conflicts and missions such as Iraq and Afghanistan, was driven by former memorial director and Liberal minister Dr Brendan Nelson. He found his contact with recent veterans such a moving experience that he felt their service was not recognised sufficiently.

Dr Nelson’s heartfelt beliefs cannot be doubted, but whether these should have been imposed on a Memorial with an award-winning building barely 20 years old is questionable.

Anzac Hall is now gone as part of the early works demolition and clearance program that somehow was approved separately from the actual construction program or main works that are still to be signed off.

And despite objections from a range of prominent Australians, including former Memorial directors, Dr Nelson will get his bigger Memorial.

But it won’t be a victory without casualties.

The Australian Institute of Architects will lament the loss of a great building and the precedent it sets for disposable architecture.

There will be concerns about how little protection the national capital’s heritage really has when the political will is there to ride roughshod over it.

But probably the most significant collateral damage could be to what may be called the soul of the Memorial, including its growing financial relationship with arms manufacturers.

Former Memorial Director Brendan Nelson was deeply moved by the veteran experience. Photo: File.

This redevelopment will only entrench the now prevailing view that the arms dealers deserve a seat at the table, blurring the lines between government, military and industry in what was meant to be a civilian enterprise to remember the service of citizen soldiers in the defence of the nation.

The expansion, and with it the addition of more war machines as exhibits, will also tip the balance towards the Memorial becoming a military museum and, whether redevelopment advocates like it or not, encouraging a glorification of the nation’s exploits at arms.

The Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts also pose problems for how they are portrayed. Some will argue insufficient time has elapsed to tell these stories with detachment, particularly Iraq, which is haunted by accusations of being an illegal invasion that reaped a whirlwind that is still devastating that part of the world.

Will visitors to the new Memorial come away with an understanding of the tragic waste of war as well as the sacrifices made in our name, or will they be dazzled by the artefacts of war and beguiled by the heroics of our troops?

It is said that the first casualty of war is truth, and in this debate about the future of the Memorial the cloak of Anzac has been all too easily cast over it to question people’s respect for the fallen and loyalty to their country.

Those such as federal Education Minister Allan Tudge seem to think that commemoration and an honest appraisal of history are mutually exclusive when it comes to Anzac.

His attacks on the draft national curriculum for allegedly promoting a “negative view of our history” that could affect our youth’s willingness to defend Australia exemplifies the dangers of fostering an Anzac ideology.

“Anzac Day should not be a contested idea. It is the most sacred day in the Australian calendar,” he said.

But without such examination, Anzac simply becomes a cult of ancestor worship that diminishes the sacrifices of war and condemns us to forget its lessons.

If the new Memorial is not to be a monument to militarism, then its galleries must be faithful to the truth, not let the artefacts overshadow the humanity and re-commit to commemoration.

Lest we forget.

Original Article published by Ian Bushnell on The RiotACT.