Forestry Corporation ecologists had their work cut out for them last week as they trekked through the dense Bondo State Forest east of Tumut in search of tiny Northern Corroboree Frogs. Photo: Forestry Corporation of NSW.

Anyone traipsing through Bondo State Forest – which lies to the east of Tumut – would be forgiven if, above the cacophony of nature last week, they heard fellow wanderers of the human kind calling frogs.

This somewhat curious practice was actually science in action and involved Forestry Corporation ecologists spending the week walking through the forest calling “hey frog”.

It is regarded as the most effective survey technique for detecting the critically endangered, tiny and brightly striped yellow (or lime-green) Northern Corroboree Frog.

Amazingly, yelling ”hey frog” elicits a response from the frogs, which call out in response.

Without this technique, the frogs would remain hidden in the wetlands, according to Rohan Bilney, a senior field ecologist with Forestry Corporation.

The survey program in the Bondo State Forest is part of a broader population-monitoring effort across the species’ range, whereby Forestry Corporation ecologists are collaborating with the NSW Department of Planning and Environment’s Save Our Species scheme.

“In late summer, the male corroboree frogs will call out in response to us bellowing “hey frog” in a deep voice — they are usually sitting in their nest, defending their territory,” Dr Bilney said.

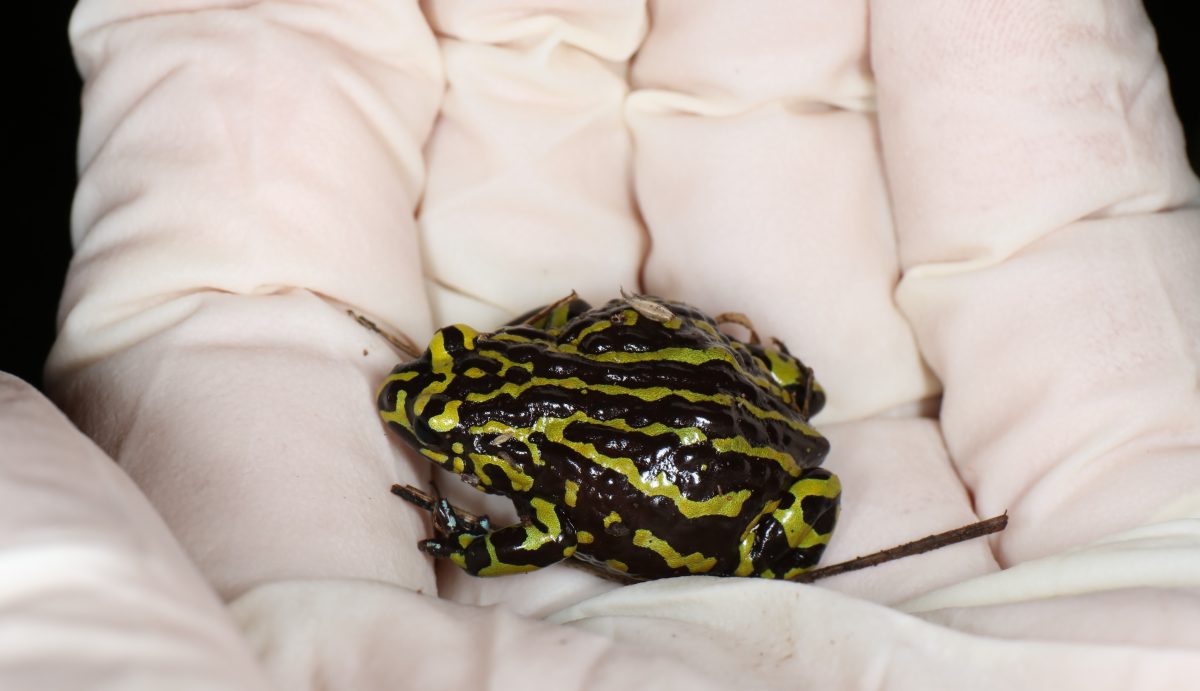

The critically endangered Northern Corroboree Frog reaches an adult size of 2.5 to 3 cm. Photo: Forestry Corporation.

“So the survey method involves our ecology team essentially wandering through the swamps and bogs in the forest calling ‘hey frog’ to see how many we get calling back.”

The monitoring program has now been running for more than 30 years, in essence, to understand the health of the local Northern Corroboree Frog.

“Throughout the previous decades, we have had strong populations here in the Bondo State Forest, however, there has been a widespread decline across all populations, largely due to the disease chytrid fungus,” Dr Bilney said.

The fungus attacks the parts of a frog’s skin that have keratin in them and since frogs use their skin for respiration, this makes it difficult for them to breathe.

The fungus also damages the nervous system, affecting the frog’s behaviour.

“This year, we are very interested to see how the population is faring, following drought, wildfires, the subsequent wetter weather since the wildfires and the ever-present threat of the chytrid fungus,” Dr Bilney said.

“If numbers continue to decline, we may need to start looking at drastic options like captive breeding to ensure the species is able to persist.”

Forestry Corporation ecologists run several species-specific monitoring programs such as this to understand the health of threatened species on the state forest estate.