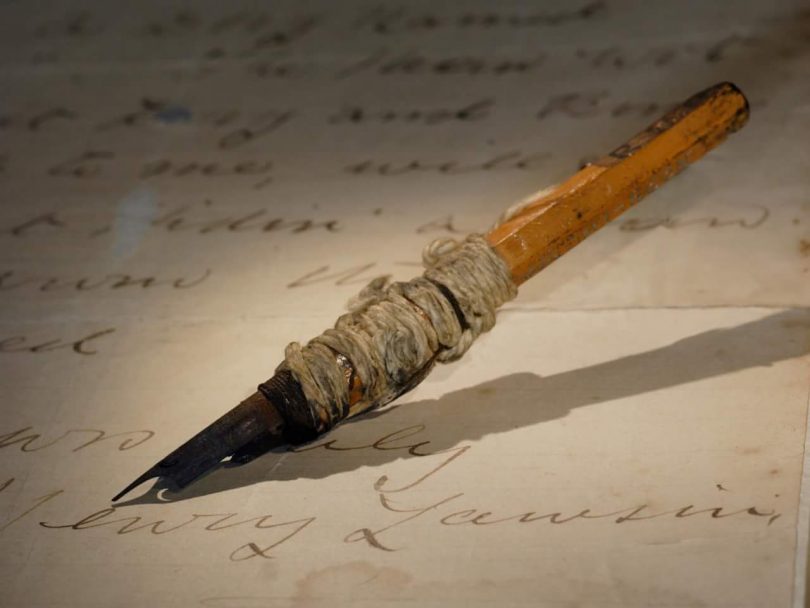

The owner of this pen knew how to tell a yarn – and legend has it, he was not one to suffer fools. His name was Henry Lawson. The pen, a steel nib wrapped in string on a pencil stub is one of the nation’s treasures. Photo: National Library of Australia.

In my line, you get to talk to some of the best people and write stories about them.

The ones who ask why you want to speak to them, they’ve done nothing special they say – except possibly achieve world peace – they’re the best ones. The ones who insist they tell you their story, especially when you haven’t asked them to, not so much.

I’ve done nothing to write home about, says the woman who lived through a childhood of bullying to become one of the leading lights in the Indigenous community, including being nominated for Australian of the Year.

She now says she is grateful to be working in her dream job – with the nation’s best collection of Indigenous material. I’ll cherish the note she sent me, in her Ngunnawal language, Yara djan yimaba (goodbye and thank you).

Then there was the guy who pledged to walk as far as he could to raise money to help servicemen and women living with mental illness. Someone close to him was battling the disease, he just wanted to help. Turns out, in the course of our chat for the story, he told me he too was suffering from the black dog, and went into detail about how it affected his life and that of his family.

His family had links back to the Stolen Generation, with family members being split up and taken to opposite sides of the country for no other reason than they were Indigenous. He didn’t blame anyone, he just lived with the consequences. Rather than crawl into a hole, he went “out there” and shared his story, raising a truckload of money that went straight to the people who needed it. Yet he got into some strife because he’d aired family stuff publicly. All he wanted to do was help.

Then there are the ones who don’t like what you write, even though it did come out of their mouth and your notebook can prove it. Turns out what people say to journalists, is, shock and horror, not always completely truthful, so when they see it in print, online or broadcast, they deny saying what you have recorded them saying. That’s OK, it seems to happen so often these days that it’s no longer even a thing.

We all have stories. Some must be told because they might just help the storyteller and those he/she cares for. Others should just be relegated to bad novels and even worse films.

I remember trying to get a word or two out of a bloke who was the brother of a well-known rock star. The reason I was told to do the interview was because he was, wait for it, the brother of a rock star and we were after some behind-the-scenes dirt. Well maybe not dirt exactly, just some juicy bits.

He agreed to the interview, but then told me he didn’t want to talk about his brother, the rock star. He just wanted to talk about his own career, except he didn’t actually have one. Sigh. The interview was short, not so sweet.

But the worst is when you meet someone you have been in awe of since you’ve known what that word means. Writers, actors, people you’ve looked up to forever – because most children are quite short.

There have been a few shockers, no names no pack drill. I won’t tell you his name, unless of course you offer me vast amounts of money and most of Tasmania, but he is a well-known, very tall actor who was often pictured coming out of the sea not wearing a lot of clothes.

He plays great quintessentially Aussie characters – you know the sort, dry wit, impossibly handsome without knowing it, always says something funny and you laugh even if it’s not. The sort of bloke even your mum would like.

Well, when I interviewed him a lifetime or two ago, he was a shocker. Late, rude, patronising and kept looking over his shoulder at either the mirror or to see if someone more interesting had come in.

Now, that’s what you call shock/horror.

Original Article published by Sally Hopman on Riotact.