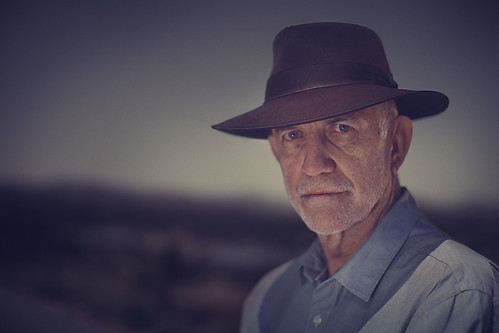

Tathra’s Graham Walker spent 21 years in the Australian Regular Army included active service in Indonesia and Vietnam. Photo: Australia Day Council.

A few years ago, Vietnam veteran and historian Dr Greg Lockhart came across the graves of the crew of a Bomber Command Stirling aircraft which crashed on the Island of Ile d’Yeu off the French Atlantic coast on October 16 1942.

The crew included four New Zealanders, two Britons and a Canadian.

For some years the families knew only that the crew was Missing-in-Action. And for three aged siblings of the pilot, Canadian John Ekelund, the first effective confirmation of their brother’s death came from Dr Lockhart in 2012

Even after 70 years, it was a relief for them; at last, they were able to grieve.

Today, in remembering the fallen, we honour the sacrifice of that bomber crew. At the same time, we recognise the families’ sacrifice; the agony of waiting.

Indeed, waiting is ‘the lot’ of every family whose loved one goes off to war. They wait, quietly dreading a knock on the door and a uniformed officer and padre saying “We have some bad news…”

And the bad news is not always of the fallen.

On Sunday the 25th of April 1915 Vernon King, a former Albany resident, landed on the Gallipoli Peninsular with the 11th Battalion.

“We got a hot reception.” he writes, “I got in the hottest part of the firing line and saw all my best cobbers falling…a shell blew up the bank that I was on and tossed me over a steep hill about 200 feet deep.”

Vernon was evacuated, returning however in June to more fierce fighting and artillery bombardments.

“I had a bad turn,” he writes, and “went stone blind for a while.”

He was evacuated again, eventually returning to Australia suffering Shell Shock. He was a changed man. Distressed by his memories, Vernon was reluctant to speak of these experiences and avoided Anzac Day commemorations.

On Anzac Day 1969, Roy Mundine, of the Bunjalong people, was on an operation with the 5th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment in Phuoc Tuy Provence, Vietnam. While moving forward to clear a bunker system, Roy tripped a mine.

“I was engulfed by a huge explosion,” he says, “then realised my leg was in tatters.”

He continued to direct his troops but later lost the leg.

“I had hoped for a continuing career as an infantryman,” he says, “but I had to think again.”

On the 14th of August 2006 Sarah Webster, from Brisbane, was in the Green Zone in Baghdad, Iraq. A 122mm Ketyusha rocket crashed into a concrete wall nearby. There was a devastating blast.

“I remember nothing,” she says, “till regaining consciousness in hospital.” Among other wounds, her leg was seriously damaged. Sarah’s career has been limited and shortened.

The wounded; so often denied the dreams of their youth, today we honour their sacrifice.

And the families of the wounded; so often their worlds turned up-side-down, finding themselves with the life-long task of care and support, today we honour that sacrifice.

And consider that chilling statistic from the Vietnam War, that the children of Vietnam veterans have a 300% higher suicide rate than their peers in the Australian community, today we might shed a tear for them.

Indeed, Anzac Day is a day on which we might remind ourselves that the cost of war does not end with the warriors’ homecoming.

So what can we salvage from the tragedy of war?

Under the threat of death on the battlefield, the Anzacs aspired to the values of courage, loyalty, trustworthiness, rejection of pomposity and above all, selflessness.

From this code of behaviour come the deeds we so admire; William Earl, on the HMAS Parramatta during the battle of Crete; with bombs landing nearby and risking being drawn into the ship’s propellers, dived into the water to rescue a crew member of HMS Auckland who was near the point of exhaustion. Mark Donaldson in Afghanistan exposing himself to enemy fire to protect his wounded comrades, then beating almost impossible odds to rescue one of his party from no man’s land.

It is this code of behaviour, too, that fosters those bonds of friendship that remain iron-clad for a lifetime. It is a code whose rewards money cannot buy. And, it is a code of behaviour whose validity transcends the battlefield.

It is a code we can all aspire to, regardless of gender, ethnicity or creed.

Perhaps it is this set of values that is the beating heart of the ANZAC tradition.

Words by Graham Walker on behalf of the Vietnam Veterans Federation.

Graham Walker’s 21 years in the Australian Regular Army included active service during the Indonesian Confrontation and the Vietnam War. He was Mentioned in Despatches and awarded the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Silver Star.

After retiring from the Australian Army in the early 1980s, Graham shifted his focus to the domestic battleground of returned servicemen and women. In his work with the Vietnam Veterans Federation of Australia, Graham has assisted thousands of veterans to receive their entitlements, advised governments, authored research and campaigned successfully for the official history of the Agent Orange controversy to be rewritten.

He was made the ACT Senior Australian of the Year in 2014 and made a Member of the Order of Australia in 2015.

He has had a long connection with the Bega Valley and now calls the Tathra home.