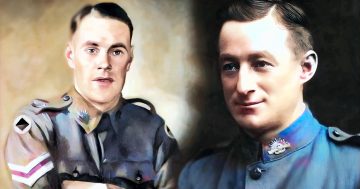

Released prisoner of war Lieutenant Colonel Anderson (left) in Bangkok, Thailand, in September 1945. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

The generations of people living in Young who would remember Charles Groves Wright Anderson are fading away.

His death in Canberra, in 1988 at age 91, made the national news. A memorial stone and plaque mark his final resting place at Norwood Crematorium in the ACT.

Young wasn’t his birthplace, but it was his hometown. A park north of the main street, just below the railway station, is named in his honour.

At its centre sits a memorial. An obelisk – a fine example of art deco design topped by a large cone-shaped torch – flanked by two walls of plaques.

The Charles Groves Wright Anderson of my childhood was a slight, bespectacled man who was often heard calling after his two dogs – Poodie, a poodle, and Honeybun, a chihuahua. His skin was pale and cool, his hands long and thin. Round glasses offset his angular features. He was a very quiet, sweet, gentle man.

Back then he was Grandfather Anderson. Not by blood, but by marriage. He was a part of our family, and us his.

He was also known as the Colonel, a title none of us tearaways understood as we were too busy doing what kids do in big houses with big gardens.

His home of ‘Springfield’ was a place of great joy and celebration, where Granny Anderson would disappear into her pottery room and the see-saw, with plow disk seats that went round and round, was terrific fun.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Groves Wright Anderson. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

On Remembrance Day, it’s impossible to reconcile that frail man in his happy house with his two dogs as a man who fought in various theatres of war. A man who displayed such fortitude, fearlessness, heroism and leadership he was awarded both the Military Cross and the Victoria Cross.

While millions of men fought in both world wars, few received Britain’s most prestigious decorations recognising their valour in both conflicts.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles GW Anderson was one of these rare men.

An early life in Kenya possibly prepared him for his first war on the side of the British against German forces as a lieutenant in the King’s African Rifles regiment during the East African Campaign in World War I.

Blisteringly hot weather, thick bushy terrain, the threat of wild animals, snakes and tropical diseases proved as formidable as the enemy, but Anderson handled the adverse conditions, fighting fiercely and bravely.

For his actions he was awarded the Military Cross – Britain’s third highest decoration for valour.

But his experience of fighting in a hot climate, often at close quarters in dense bush and difficult terrain, would prove useful later in life.

By the time war broke out again, Charles Anderson was married, a father of three and living on a property near Young.

It was said that as a middle-aged, bespectacled, veteran of an earlier war, Anderson did not look like a Hollywood-style war hero.

But by August 1941 he was in Malaya as commanding officer of the 2/19th, a battalion he had trained in the art of jungle warfare, bayonet fighting and snap shooting with a rifle.

It wasn’t long before they were fighting off advancing Japanese on the west coast, a place where he distinguished himself both as an officer and a gentleman in command of a small force of Australians and Indians.

During the Battle of Muar from 18 to 22 January, 1942, Anderson commanded a small force that destroyed 10 enemy tanks which left them cut off from the main force.

So amid air and ground attacks, Anderson led his troops through 15 miles of enemy territory, at one point personally taking out two machine gun posts with his revolver and a few grenades. His efforts to clear the way for his men to advance saw his involvement in gruesome hand-to-hand fighting and bayonet charges.

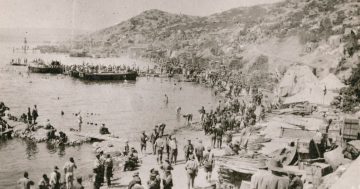

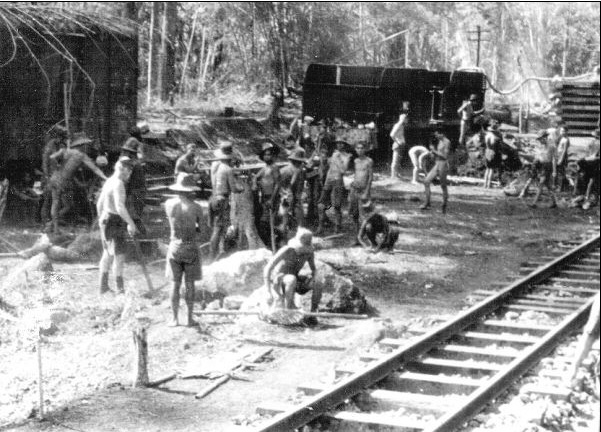

Lieutenant Colonel Anderson became a prisoner of war, commanding ‘Anderson’s force’ on the Burma-Thailand Railway. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

At Parit Sulong, the contingent was halted by Japanese forces who had retaken a bridge that stood between them and the retreating main Allied Force.

Surrounded, outnumbered and lacking reinforcements, Anderson’s team fought to recapture the bridge and for days maintained their position, refusing to surrender despite suffering horrible casualties from tank, machine gun, mortar and air attacks.

Then Anderson attempted to lead his men through eight miles of enemy territory to Yong Peng, but this proved impossible. Forced to destroy their equipment and vehicles, the men were ordered to escape through the jungle and meet up with the main force.

For his brave actions and leadership, Anderson was awarded the Victoria Cross. But it didn’t end his war.

He was taken into captivity on February 15, 1942, and endured the misery and squalor of being a prisoner of war and commanding ‘Anderson’s force’ on the Burma-Thailand Railway.

Despite a high rate of death and illness, he maintained a high level of morale among his men, all of who would have followed him to hell and back.

He survived to return to family, farming and a political future as Member for Hume, serving three terms.

It was on November 11, 1988, Charles Anderson died in his home at Red Hill.

He was cremated with full military honours.