Alberta Hornsby. Photo: G Jacobs.

Australia is filled with reminders of Captain James Cook and his voyages. But when Alberta Hornsby gazes at a map of the Endeavour River in Far North Queensland, or a long list of names and words, the Guugu Yimithirr elder hears voices murmuring in her own tongue, sees other faces than that of the famed navigator. She sees her own people.

When the National Library of Australia set out to stage an exhibition around Captain Cook’s remarkable voyages of exploration, they faced a 21st-century conundrum. Two hundred years of Western history have focused on the great navigator more or less to the exclusion of the many people he met along the way.

But when Cook arrived on this continent, he also set the stage for dispossession, disease and death in his wake. So how, then, to tell the story of Cook’s voyages in a way that honoured two stories, two perspectives and two legacies?

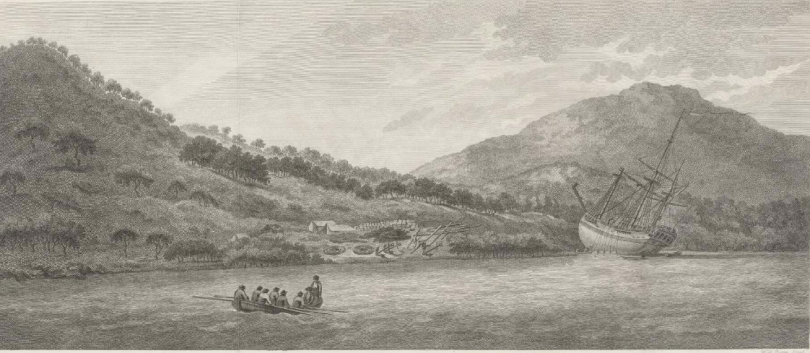

“A view of Endeavour River, on the coast of New Holland, where the ship was laid on shore in order to repair the damage which she received on the rock”, Will Byrne, 1773. Image: NLA.

It was a question Alberta Hornsby has pondered deeply herself. When she and her late uncle, Eric Deeral, the first Aboriginal man to be elected to the Queensland parliament, began looking for their own stories embedded in the records of Cook’s voyages, they did so with some trepidation.

Captain Cook and the Endeavour crew arrived at the place known as Waalumbaal Birri in 1770. “They didn’t realise that it was a very special place where surrounding clans from that country gathered,” Alberta says. “Women gave birth there and clans came there to settle disputes. Initiation happened there, resources were shared and even marriage alliances were formed. And so by important law, no blood was to be spilt on that land. Cook knew nothing of that.”

The Guugu Yimithirr bided their time. For many days they watched Cook and his men fish, repair their boat and shoot pigeons. Then, they made their move. Cook observed through his telescope groups of women watching as two men crossed the water in a canoe, pretending to strike at fish.

“The men had red and white pigment on their skin and raised scars on their chest. The colours meant that they were chosen for the job,” Alberta explains. “Their scars showed they were fully initiated, men who had passed all the tests and knew they were possibly approaching trouble. The white signified they were calling for protection.”

Cloth, nails and baubles were thrown overboard to the men but ignored until the two groups found common ground over a fish. With the help of Maori interpreter Tupaia, the first recorded contact took place between Cook and the people of eastern Australia.

“A Plan of the River on the East coast of New Holland….” by Richard Pickersgill, 1770. Image: NLA.

The half dozen meetings were friendly, and Cook’s men made many observations. “Parkinson collated 150 names,” Alberta says. “The first word, which the visitors assumed meant ‘man’ was, in fact, Bamma, which we use to describe who we are as human beings. That gives us back our identity. It is who we are.

“The word list contained the names of nine men. At least three of those words are kinship terms from different clans, one from my grandfather’s ancestral lands. We know who we are and that’s a continuous connection from 1770 to this day.”

The National Library’s decision to engage fully and proactively with First Nations people was fundamental. The first thing visitors see as they enter the exhibition is a welcome to country from Ngunnawal custodian Paul House, and messages from members of the Samoan, Tongan Maori, and other communities.

Inside, there are magnificent ceremonial objects including a Tahitian chief mourner’s costume. Traditional custodians provide insight into the meaning of objects like tattooing tools and comment on how their ancestors have been depicted by Cook’s observers.

Alberta Hornsby says, “We celebrate ANZAC, all of these conquests yet we fail to celebrate the beginning and the birth of this nation as equal peoples, two stories side by side. Equal histories. We need to take our place in the forming of this nation and in history.”

Just before Cook and his men departed, there’d been conflict with the Guugu Yithimirr over turtles the crew had taken. An old man emerged from the bush trailing a broken tipped spear. Wiping sweat with his hands he blew it into the air, asking the ancestors for protection but showing he came in peace.

“Now to me, that’s a remarkable event because our people couldn’t spill blood on that land,” Alberta says. They would have been frustrated but they re-gathered and this little old man set the scene to make peace. Cook immediately understood the gesture though he could not understand the language. He knew it was a process of resolving conflict.”

Alberta hopes that the care taken at the NLA to balance the stories of everyone involved will help to break down the obstacles that lead to “a proper dialogue of treaty or reconciliation, whatever that political story is. There needs to be a stage where an open dialogue can begin.”

Cook and the Pacific is at the National Library until February 10, 2019.

Original Article published by Genevieve Jacobs on the RiotACT.