Not much vegetation just outside Nyngan on the way to Bourke. Photos: Maryann Weston.

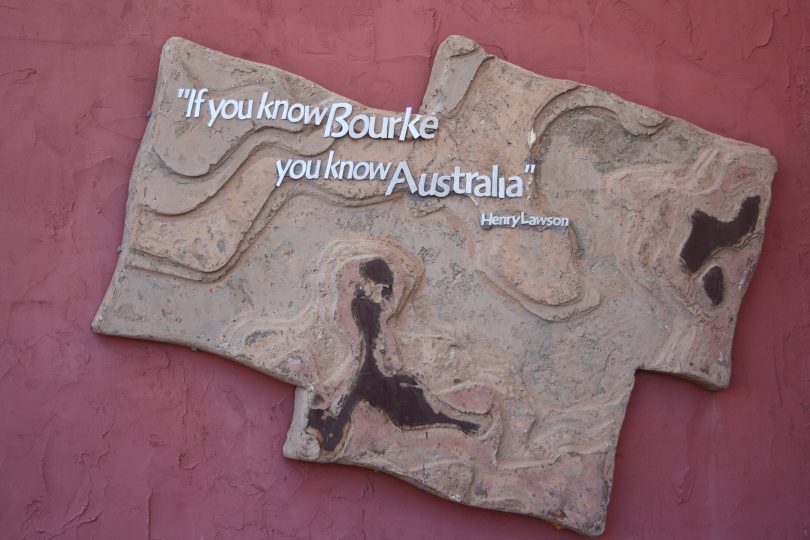

“If you know Bourke, you know Australia,” according to iconic bush poet and writer Henry Lawson.

A recent trip through the central west of NSW to this outback town was evidence of that, as the seriousness of the drought in Bourke is reflected in towns right across Australia.

It’s old and familiar territory.

I was born in the outback, less than 200 km from Wilcannia. My father used to play cricket at Bourke when the Wilcannia team took on the Bourke side, no doubt on bone-dry pitches. Times might have changed but the droughts just keep getting drier.

It’s not just me.

Anecdotal and climate evidence from locals and the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) paint a clear picture. Take a look at the rainfall maps and most of Australia is in the vicinity of ‘below average’, ‘very below average’ and ‘lowest on record’. In Goulburn and the ACT we are faring a little better, but in the central west and outback, rolling whirly whirlies or, worse, low-slung cloud banks of red dust are commonplace.

The BOM says “drought is not simply low rainfall”, it’s a “prolonged, abnormally dry period when the amount of available water is insufficient to meet our normal use”.

Landscape artist and operator of the Back O’Bourke gallery Jenny Greentree standing in front of her artwork which forms part of the exhibition Hope on the Horizon.

Bourke landscape artist Jenny Greentree has been in Bourke for 23 years. She operates the Back O’Bourke gallery on the outskirts of the town. This is the first time she’s seen the Darling River run completely dry.

It’s flowing now in the weir section in town due to rainfall in May which brought water from Queensland but, on the whole, the once-mighty Darling River is receding and largely dry.

“Last summer I could walk across the river behind my house. When it rains in Queensland, we get that water in the river about six weeks later but it seems that less and less is able to get here now,” Jenny said.

While locals might not be able to say ‘this is the worst drought’, they do say it is the most prolonged.

“In 2000 and 2007, we still had flows in the Darling. People who come into the gallery tell me their grandfathers are saying they’ve never had waterholes that have gone dry before,” she said.

A weir has been created on the Darling River at Bourke.

Downstream the Darling ran dry before rains flowed from Queensland earlier this year. Less and less water is arriving from Queensland, according to locals. An Indigenous festival, the Yaama Ngunna Baaka Corroboree Festival, coincided with my trip to the Outback which brought together Aboriginal and non-Aboriginals concerned about the Darling (Baaka) River.

Bourke is already on bore water, for the first time in Jenny’s experience. As a landscape artist, she has an intimate relationship with the land on which she lives. There is always hope, she said.

“I set my gallery to a theme each year and this year the exhibition is ‘Hope on the Horizon’ in response to this drought. There is a strength and a tenacity to this landscape and I’m amazed by it. I see that same strength and tenacity in the people who live here.”

We drove into dust whirly whirlies frequently, including a dust/rainstorm from Canowindra to Dubbo.

In Dubbo in the central west and the surrounding regions, the drought is “much more severe because of its profile”, head of the Rural Financial Counselling Service NSW Central Region, Jeff Caldbeck said.

“There is a lack of soil moisture, surface water and vegetation and that knocks everything around,” he said.

“From here to West Wylong there is an area between Parkes and Dubbo known as the ‘Golden Mile’. In 13 years of travelling that route, I’ve never seen it without a crop until now. Farmers are battening down the hatches and some are totally destocking because there’s no money for feed.

“Remaining stock has to be fit enough to send to market and so the situation is compounded if there’s no money for feed and you can’t shift them, then farmers have to euthanize their stock.”

Getting assistance from Centrelink under the Federal government’s Farm Welfare program is another issue, Jeff said. To get assistance requires audited financial statements and farmers simply don’t have the money to pay for the audits. As a result, accounting and financial organisations are digging deep and doing them for free.

Henry Lawson worked and wrote prolifically in and around the Bourke region and knew it well.

For now, the banks are being judicious in calling in farm loans, Jeff said.

“We are starting to see some activity with third-tier lenders but the ‘big four’ are holding firm.”

He said the big challenge is the mental impact of drought and severe financial difficulty.

“It’s soul-destroying. BOM isn’t predicting rain but if they acknowledge that, then hope disappears. What holds the depression factor at bay is hope and if there’s no rain then that will be a huge tragedy. It will also affect rural communities and irrigators as well.”

If you want to donate to drought relief, St Vincent de Paul is fundraising for NSW farmers.

Just outside Bourke where the landscape is dry but has a resilience that is mirrored by the locals.

Original Article published by Maryann Weston on The RiotACT.