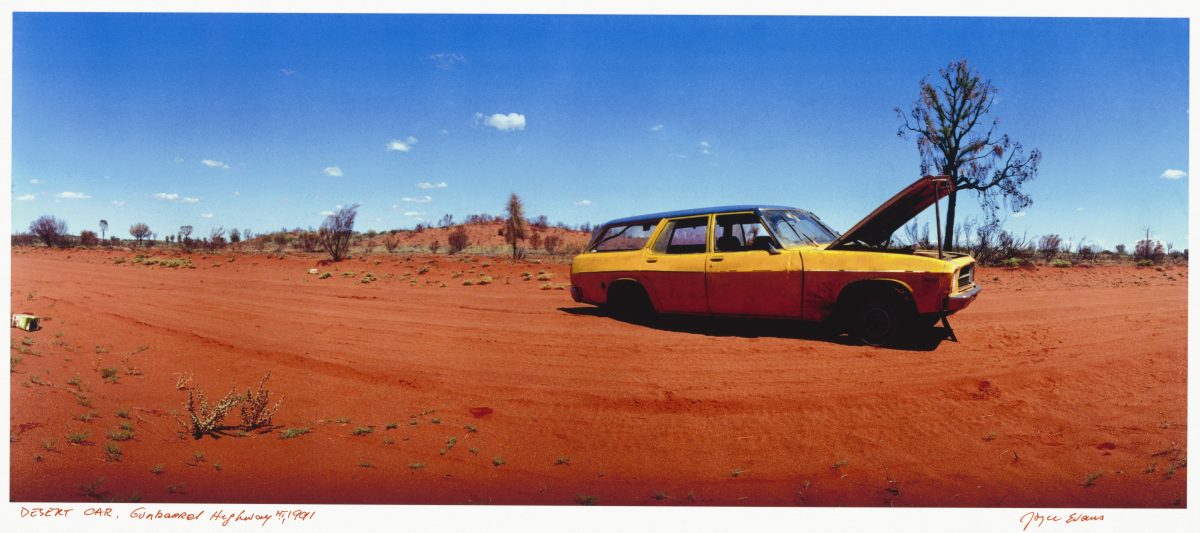

Joyce Evans, Desert Car on Gunbarrel Highway, Northern Territory, 1991, nla.obj-153485555.

Although everyone working professionally in Australian photography has heard the name Joyce Evans (1929-2019), few outside this circle would know it.

The National Library of Australia has recently acquired Evans’s entire photographic oeuvre – over 30,000 analogue images and 80,000 digital files – one of the largest collections of any photographer in Australia – and now the NLA is staging an exhibition of her work.

Joyce Evans was an unusual phenomenon in the Australian photography scene. Her conversion to photography did not occur until she was already in her 40s, while her engagement in professional photography had to wait until she was 50. She never developed a signature style, nor had she become a template photographer, but she possessed a definite photographic personality.

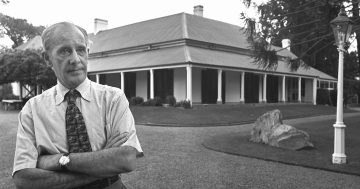

Joyce Evans, Cotswold Farm, Menzies Creek, Victoria, 1982, courtesy National Library of Australia.

Evans opened one of Australia’s earliest commercial galleries dedicated to photography in Melbourne in 1977 and a few years later turned to making her own studio photographs. An early master photograph was made at the Cotswold Farm, a flower farm at Selby in the Dandenong Ranges, studying the spectacular formal elements of the design, the seas of yellow and recording traces of human habitation. She settled on the final image after about 30 or 40 photographic sessions at the site.

Joyce Evans, Windmill on Lake George, New South Wales, 1983, nla.obj-153304178.

On the strength of this photograph, she was offered a solo show at the prestigious Realities Gallery in 1986 where Clyde Holding, who was then the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs in the Hawke Government, fell in love with her photograph Windmill on Lake George, New South Wales, 1983, and acquired it for himself.

Holding invited Evans as an honorary documentary photographer for visits to remote Aboriginal communities in 1987 as part of the Petrol Sniffing Prevention Team. This was the beginning of Evans’s work as a documentary photographer.

Joyce Evans, Gertrude, Boola Boolka Station, New South Wales, 2006, nla.obj-153040091.

Subsequently, Evans was commissioned by different institutions to record the rural towns of Australia, take portraits of prominent Australian artists, writers, poets and patrons and explore aspects of the lives of First Nations peoples. As a photographer, she was dedicated, exceptionally hardworking and prolific.

As an erudite scholar of the history of photography who had amassed a substantial collection of international and Australian photographs, Evans’s photographic eye was exceptionally well-informed.

As a studio photographer, she frequently spent many hours, even days, waiting for the correct conditions to take the perfect photograph.

As a documentary photographer, Evans considered herself a hunter and gatherer waiting to find the image. She remarked, “as an artist, you channel the energy of the place – the image comes to you as a gift”.

Her oeuvre is remarkable for its diversity and includes landscapes, roadkill, portraiture, social documentation, brothels and erotica – all brought together through a unifying sensibility, the Evans photographic moment. She was also an artist with a social conscience and pursued an agenda that shone a light on racism, social inequality and environmental degradation.

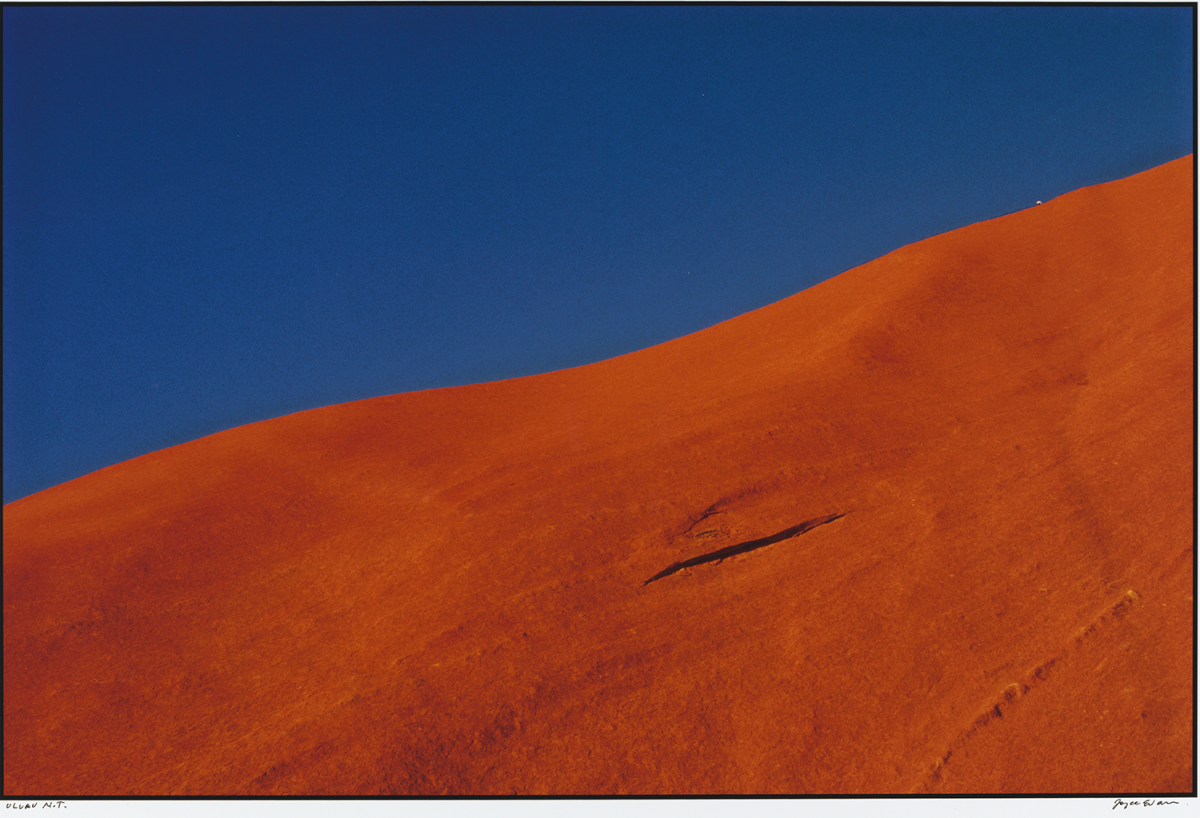

Joyce Evans, Uluru, Northern Territory, 1987, courtesy National Library of Australia

Many of Evans’s photographs demand slow viewing and open up gradually. Uluru, Northern Territory, 1987, shows the rock as if carved by nature. In one sense, it is a very simple photograph in which two colours meet—the brilliant red ochre of the rock and the fathomless blue of the sky. It is also an immensely complex photograph with the mysterious slit—like the womb of the earth—in the centre of the composition and galvanising the viewer’s attention.

Gradually, as you focus into the image, there are signs of human presence at the top of the rock: two climbers on the chain pathway, contrasted with organic shapes created through centuries of erosion—a contrast between the temporal and the eternal. Despite the sense of stillness and silence, there is also considerable movement as the light plays over the textured surfaces.

The photograph is rare in that it defines a space but also distils the spiritual essence of the place and asserts an atmosphere of mystery and contemplative presence.

In 2016, when I was working on a monograph on Evans’s work, she noted: “As a photographer – I have a voice – it is an Australian voice, as I do not know intimately any other culture. It comes at a time when you say: ‘This is my country’. One of the sub-texts, when I pick up a camera, is that I always try to identify the stereotypical that is always defined by that which is on the edge.”

Joyce Evans: Collection-in-focus exhibition, National Library of Australia – Treasures Gallery, Parkes Place, Canberra, closes 5 November 2023.

Original Article published by Sasha Grishin on Riotact.