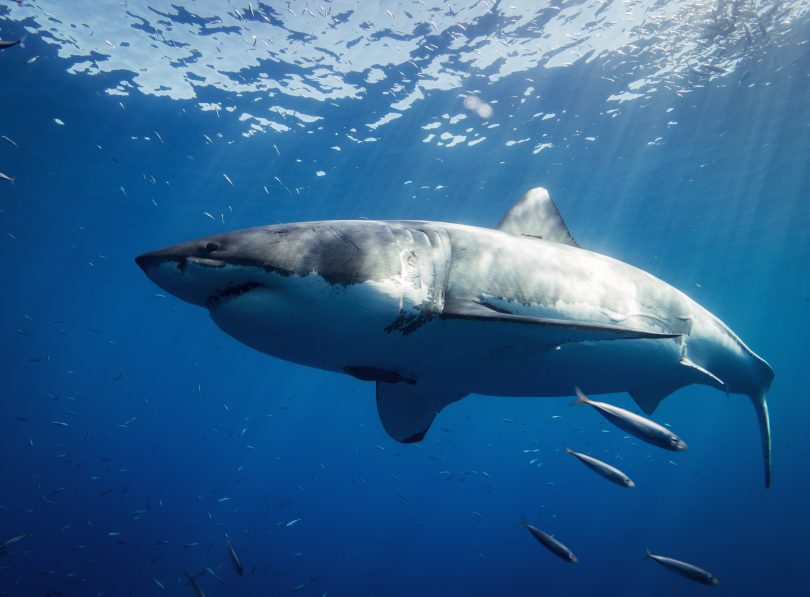

Great white sharks (pictured) and tiger sharks are the most commonly sighted sharks on the NSW South Coast. Photo: Gerald Schombs.

It has felt like a busy summer for shark activity on the NSW South Coast, with 50 of them sighted in the waters between Moruya and Broulee in November, 2020, followed by more in December as a whale carcass floated close to the coast, and another 10 seen swimming below surfers at Broulee on Wednesday, 13 January.

What’s more, 2020 was the deadliest year for shark attacks in Australia in nine decades. Eight Australians were killed by sharks in NSW, Queensland and Western Australia, including former Canberra real estate agent Nick Slater.

Shark experts say the current La Nina weather pattern has created the perfect conditions to draw sharks closer to shore.

Yet the total of 26 shark attacks recorded in 2020 by the Australian Shark Attack File, an initiative by Taronga Conservation Society Australia, isn’t unusual according to Macquarie University biological sciences professor Culum Brown.

Of those attacks, 22 were unprovoked and four were provoked, which means the shark was attracted to the victim by activities such as fishing or the victim was feeding, netting or handling a shark. While eight people died, 11 survived with injuries and the other seven were uninjured.

Those on the ground on the NSW South Coast, such as Lifeguarding Australia CEO Stan Wall, say the numbers we’ve seen so far in January 2021 aren’t uncommon.

So why does it feel as if there has been more sharks swimming closer to the shore this summer?

Professor Brown says it is possible La Nina has created an increase, but the data to prove this isn’t available yet.

People such as Professor Brown and the NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) are only able to gain access to data from tagged sharks every six months.

March will be the next time Professor Brown gets to take a look at preliminary data.

So in the meantime, how could La Nina be influencing increased activity? Professor Brown says the weather pattern has a big influence on marine ecosystems and has historically been associated with an increased presence of sharks where humans swim.

“Increased trade winds across the Pacific drag hot surface waters to Australia’s East Coast, which is why if you go swimming on beaches in NSW right now, it’s hot,” explains Professor Brown. “These hot waters lack nutrients so fish are searching for the cooler spots and sharks are following them.

“When those cool spots correspond with shallow waters on the coast, that’s when there’s a big chance for fish, sharks and people to interact.”

Perhaps what has been more significant, and subsequently raised our awareness of sharks close to shores, has been the recent record in shark attack fatalities.

Dr Phoebe Meagher works on the Australian Shark Attack File and says while last year’s fatalities were high, it’s hard to explain why without speculating, and instead puts it down to terrible luck.

“Whether or not an injury is fatal may not have anything to do with the number of sharks or where they are, but perhaps more to do with factors such as how long it took the victim to get into shore, whether the beach was patrolled or had easy access for paramedics,” she says.

Professor Brown agrees and believes Australia should invest more into studying sharks rather than putting up shark nets and SMART (shark management alert in real time) drumlines, which he says are ineffective.

“One of the things I’m really keen on is using technologies, particularly drones [to track sharks],” he says. “There is a hybrid drone that can stay up for a really long time. If you have one of those at a busy beach, you can be detecting sharks in real-time and saving that into a computer.

“You don’t even need to have someone looking at that data because we’ve got smart intelligence that uses artificial intelligence to look at images and detect if sharks are there. Sometimes the programs are so good they can tell the species.”

Despite the advice of people such as Professor Brown, the NSW Government will spend its biggest expenditure to date – $8 million between 2020 and 2021 – on a new strategy to protect beachgoers from sharks, including SMART drumlines and nets.

SMART drumlines are able to detect sharks before they reach the surf break and allow researchers to catch the sharks and tag them.

However, the strategy also includes drone surveillance, which is used in collaboration with surf lifesavers on the NSW South Coast.