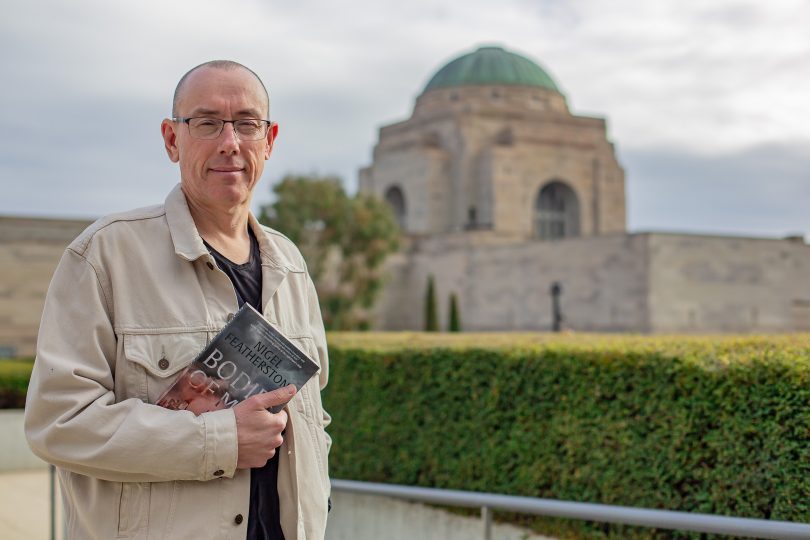

Nigel Featherstone at the Australian War Memorial with his novel, Bodies of Men (Hachette). Photos: George Tsotsos.

Nigel Featherstone writes a good battle scene, a good love scene and a good story.

And while Bodies of Men, the story of two men’s passionate love affair during the Western Desert campaign is a spare, elegant and beautifully written book, it’s the complexity of ordinary lives that rivets the author.

The novel began in the Australian Defence Force Academy’s Canberra library, with a fellowship that the Goulburn writer had never expected to receive. Thumbing through shelves of books about “the history of the AK47, or Rommel’s strategic thinking”, he wrote in his diary “I have no idea what I’m doing here. I am all at sea”.

The turning point was historian (and former Australian War Memorial principal historian) Professor Peter Stanley’s 2010 book Bad Characters, predicated on the idea that an army reflects all the human diversity of the society that it comes from. “I started thinking that while the Army might try to create one image of soldiers, there must be all sorts of actual experiences in war, not just the same old ones about people going over the top.”

That, in turn, led to an exploration of masculinity and wartime expectations. “I wondered how many men went to the war and came back feeling like real men because they had shot someone, taken the life of some other ordinary person? Is that what makes you a man?”, Nigel says.

The book’s lead characters James and William share a love story that begins in childhood. It’s suffused with tenderness as well as passion: both come from families hiding difficult secrets and Featherstone beautifully evokes the spark between people suspended in that breathless moment when the possibility of love is first recognised.

William is from a prosperous family, with a politician father who has truly brutal expectations about his sons’ roles in life. James is raised by his mother, a campaigning shop-keeper with ideals around social justice. They are separated by William’s father but meet again in 1941. James saves William’s life and reputation as an officer in a tensely written battle scene, but then deserts to Alexandria.

Taken in by a German Jewish family with their own secrets, he gradually heals from a major motorbike accident while being pursued with increasing vigour for desertion by Army provosts. It’s there that the relationship with William flowers, amidst the danger of imminent capture. Their relationship is risky in every way but it’s also an enduring slow burn that will transcend their physical lust and the wartime setting.

Bodies of Men is grounded in extensive research undertaken during a writer’s fellowship at ADFA in Canberra.

Alexandria, full of alleyways, sunny courtyards and lights sparkling on dark water, is vividly realised, as are the blinding sand storms, the nerve sapping torpor and enervation of endless desert patrols.

Nigel was struck by a statistic Peter Stanley gave him: “Of the million men who served in the Second World War, only 100,000 ever served at the front line. So for every man at the front, there were nine others behind the lines to get them there.

“What was life like for those further back when it’s boredom, boredom, boredom, then crazy decisions and chaos and then boredom again? What did it mean for people to live through that and wonder what role they were expected to play, how they were supposed to be a soldier?”

Desertion fascinated him too, as he read the records of men who were threatened with court-martial and prison. “I started thinking that there was no single moment of decision about deserting. People can be fully involved one day and absent the next. If their superior was a father figure, if there was mutual respect, they could do wonderful things. But sometimes desertion, not pulling the trigger, can also be an act of bravery.”

Nigel began his writing process in 2013, shaping the book through the four years of ANZAC commemorations. He observed “the whole amplification of aggressive masculinity” through the centenary years, the sense that a single story was being crafted about Australians at war rather than the messy, complicated reality of people’s real lives.

As the war story ends, William realises that Alexandria, not the battlefield, was where he learned to be a man. But what that means defies easy categorisation for anyone who served.

Bodies of Men is available at all leading bookstores.

Original Article published by Genevieve Jacobs on The RiotACT.