Areas of snow gum grasslands and woodlands on a property in Monaro. Photo: Colin Elphick/NSW Biodiversity Conservation Trust.

Oil and gas giant Woodside Energy is buying huge blocks of farmland to help offset its carbon emissions. It paid $23 million for 4300 hectares of grazing land in the Monaro.

There is some concern in the community that the environmental benefits of carbon farming are overstated and the long-term costs to the environment and rural communities are being overlooked.

Selling agent Rawdon Briggs of Colliers said the large purchases of farmland by Australia’s largest emitters had noticeably picked up over the past two years.

“I don’t see that changing in the short-term because most of the companies participating in the market are trying to achieve the 43 per cent reduction in their emissions [from 2005 levels] by 2030 as per the Albanese Government’s commitment,” Mr Briggs said. “Those 213 heavy emitters that need to achieve those sorts of reductions will be participating in various abatement processes in the next few years to make sure they can continue to grow their companies.”

Fifth-generation farmer and board member of Monaro Farming Systems, John Jeffreys, said Woodside had paid around the market price or a bit over “but not stupidly”.

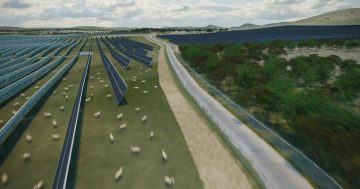

Mr Briggs said the Government’s Clean Energy Regulator required companies in the scheme to plant species endemic to the area. “Five to 10 species will be planted from seeds off the property and around the periphery to re-establish the native species.” He said the seeds would be planted in rows far enough apart for grass to grow and to give machinery access.

Upper Snowy Landcare Network project manager Lauren van Dyke said they were still trying to understand the tree planting aspect of carbon farming. One concern is that parts of the region are native grassland. “Grasslands are a specific habitat and should not have trees on them because they can’t sustain trees,” she said. “When planting, reference should be made to the relevant plant community for that site.”

Mr Briggs said cattle would continue to graze on the land to both increase returns and mitigate fire risk and Woodside would employ a farm manager.

Mr Jeffreys, who has closely examined the carbon offsetting scheme, said the fire hazard issue was just one of several problems in what was a flawed process.

“The fact Woodside thinks it must become a large land baron on the Monaro suggests there is a problem,” he said. “Any rural community would welcome funds for land stewardship programs and tree planting in a planned manner within the landscape but fraudulently subsidising the corporate sector to soak up local farmland assets is not a smart way to do it in the long-term and it devalues rural communities.”

John Jeffreys is a fifth-generation farmer and a board member of Monaro Farming Systems. Photo: Supplied.

“As has proved to be the case with a number of the other carbon farming methodologies, the Native Forest Regeneration Method also appears to significantly overstate the level of carbon abatements,” Mr Jeffreys said. “Once trees are planted, investors are simply paid based on a computer-generated model.

“That model significantly overstates realistic growth rates with returns in excess of $1000 per hectare, which is absurd,” he said. “Under this corporate model as experienced in New Zealand, revenue from these carbon programs largely flows out of the rural communities they impact.”

Mr Jeffreys said most farmers in the region would happily plant trees on 10 per cent of their land and be part of the environmental stewardship. That would also keep money in the community.

Instead, carbon farming had created an industry of financiers and middlemen “clipping the ticket” and that is happening at the expense of local communities.

“We have seen these things in the region in the past around Bombala,” Mr Jeffreys said. He was referring to the tax-based managed investment schemes (MIS) that resulted in hectares of farmland being turned into monoculture plantations of trees like blue gums and pine.

A Federal Parliament report on the failure of some high profile agri-based MIS in 2009 and 2010 concluded that it had “caused significant damage to investors, farmers, neighbouring communities and the reputation of agribusiness MIS”.

Mr Jeffreys said New Zealand had similar carbon farming schemes that were operating longer. “Communities have lost schools, post offices and shops,” he said. “They are currently restructuring many of those to be more user-friendly instead of all those negative social and economic impacts on the community.”

Unlike farming, carbon farming does not create many jobs – only tree planting. “There is nothing to do so there are no people,” he said. “Leave the farmers and farmland there and have smart planting in the existing landscape that doesn’t detract from the whole community.”

Upper Snowy Landcare Network is hosting a winter lunch called Carbon Market Update on 30 August.