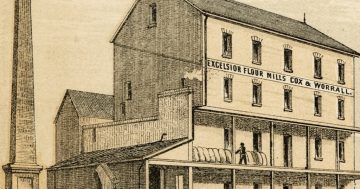

Pomeroy Mill was built in the 1870s to offer milling services to the district’s farmers. In 1875 the Australian Town and Country Journal declared Pomeroy Station’s 11,000 acres of well grassed land, 20 miles of running water and production of 35 bushels to the acre of wheat would turn it into one of the colony’s most desirable properties. Photo: Neville Friend.

More than 30 years ago, sheep grazier Michael Dalglish and his family took a hard look at restoring the Pomeroy Mill, which has stood on their property west of Goulburn since the 1870s.

The idea has arisen repeatedly over the years, along with the realisation restoration would be too expensive. Moreover, Sydney Water which presides over the outlying areas of its vast catchment would not allow anyone to live in the mill so close to the Wollondilly River.

The shadow of Sydney Water hanging over this enchanting mill would either torment or amuse the long-departed gifted engineer and naval officer Thomas Woore who built it, because Woore also proposed a scheme for supplying water to Sydney from the Warragamba River in 1866. Commended by the authority’s hydraulic engineer, his scheme nevertheless was deemed too grand for the colony.

Turns out that mill was too grand as well. Woore bought Pomeroy in 1840 and years later when wheat was growing in the district and hauled to Sydney by horse and bullock drays, the enterprising engineer spotted an opportunity to establish the mill.

Stonemason John Brown and a team of workers were engaged in building from local stone the two-storey mill and steam-powered and water-powered operation. A long water chase would ultimately power the large waterwheel.

Half a mile above Pomeroy Mill where the river fell over a ridge of rocks, those pioneer builders constructed a masonry dam from bank to bank. Then along the sloping hillside to the west, a wall three-foot thick and six-feet high was made watertight with cement. A race was dug into the foot of the wall. Buttressed by boulders on sections, the wall continued for half a mile.

But as Michael Dalglish points out, by the time Pomeroy Mill was built farmers realised there was better wheat country around Young and Harden. The mill’s operation was short-lived and it was decided to dismantle and reassemble it further out west.

But as the working parts were being dismantled, a heavy timber beam fell on one of the workers, killing him. Consequently plans to take down the entire stone structure were abandoned.

Goulburn real estate agent Jim Brewer sold Pomeroy homestead, offered on 35 acres of land in 2015 for $900,000. Photo: Jim Brewer Real Estate.

When Woore died in 1878 he had been unsuccessful in trying to sell his magnificent property. Later in another twist came the story of how the Dalglish family bought Pomeroy.

James Campsie Dalglish once loaned a man in dire need 250 pounds. Dalglish barely knew him, and as he was about to leave on one of his survey expeditions, this man came to him and said: “I can’t pay you but will you take this share I’ve bought in a mine out west?”

Dalglish said he would prefer to have the money but was in no hurry. ‘‘You try and sell your share and when I come back if you can’t pay me, I’ll take it,’’ he had said. On his return, his acquaintance said nobody would buy the share and he had no funds, so J.C. Dalglish accepted what seemed a worthless bit of paper.

It turned out to be an original share in the Broken Hill Proprietary Company and was worth 40,000 pounds per annum.

The value had grown over many years and every effort was made to trace the man who had hawked the share around Goulburn. Eventually it was discovered that he had died leaving no relation, so this fortune enabled Mrs J.C. Dalglish to buy Pomeroy for her son, Alexander Augustus Dalglish in 1898.

While the stone structure has stood the test of time, the Pomeroy Mill’s years of service were brief. Photo: DTC Photography.

Michael, who was born in Pomeroy homestead, confirms the unexpected windfall. “The peak of the Dalglish fortune was back then in the late 1800s with BHP pretty much going from nothing into the world’s largest mine,” he said.

Woore had built a magnificent Gothic-style villa with tall gables, Tudor chimneys and a fine fireplace in every room. Unlike the mill, the homestead and small portion of surrounding land has changed hands several times over the years.

Pomeroy remains a successful grazing property still in the hands of the Dalglish family.