At the official opening of Sydney Harbour Bridge on March 19, 1932, Francis de Groot rode a horse out of the crowd and slashed the ribbon with his cavalry sword. Photo: National Museum Australia.

What could possibly go wrong at the March 19, 1932, opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and what has a solicitor from Young, later, a shire president, and a secretive paramilitary force got to do with it?

As the March 19 celebrations of the 90th year of Sydney Harbour Bridge draw closer, there bubbles up the story of Eric Campbell, a man who later described himself as “Fascist to my fingertips”.

Colonel Eric Campbell founder of fascist movement the New Guard walking down a street with a group of men, NSW, 17 December 1931. Photo: National Library of Australia.

Just months before the bridge opening, Campbell called NSW Premier Jack Lang a “tyrant and scoundrel”. He was fined £2 at Central Police Court for using insulting language; a charge he successfully appealed.

In the tense atmosphere of early 1932, murmurings were rife that Campbell and his right-wing group were plotting a coup or to kidnap Lang.

The well-educated son of a lawyer, Campbell had distinguished himself on the battlefields of Europe throughout WW1.

He was gassed in France, twice mentioned in dispatches in 1918 and awarded the Distinguished Service Order in January 1919.

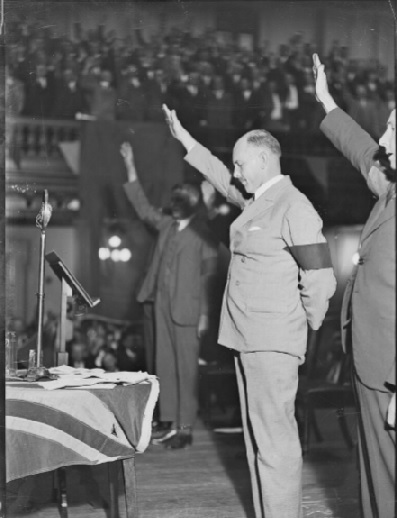

Leader of the New Guard Colonel Eric Campbell standing on a stage, NSW, 17 December 1931. Source: National Library of Australia.

After the war he resumed his legal career, initially in partnership with SG Rowe and then with his brothers as Campbell, Campbell and Campbell in a very successful practice.

He married Nancy Emma Browne, the daughter of a grazier, at “Memagong Station”, near Young in October 1924.

His first paramilitary activity occurred in 1925 when he and Major John Scott recruited a secret force of 500 ex-officers to try to quell a seaman’s strike.

In 1930 he became recruitment officer for a vigilante group of businessmen, ex-officers and graziers alarmed by the Depression and the election of JT Lang’s Labor government. They were known as the Old Guard.

Disappointed with the conservative and secretive Old Guard, early in 1931 Campbell – by then a reputable and well-connected businessman living in Turramurra – launched the New Guard which stressed loyalty to the throne and British Empire.

The guard aimed at uniting “all loyal citizens irrespective of creed, party, social or financial position” in seeking “sane and honourable” government and the “abolition of machine politics”.

De Groot was arrested, charged for offensive behaviour in a public place and fined five pounds. Image: Sydney Living Museums.

Organised along military lines, with a peak membership of 50,000, the New Guard rallied in public, broke up communist meetings, drilled, vilified the Labor Party and demanded the deportation of communists.

But rather than kidnapping the Premier or staging a coup, the Bridge opening provided the perfect opportunity for maximum publicity.

Captain Francis de Groot, a senior New Guard member, gained infamy for intervening on horseback during the official opening, cutting the tape before the premier could do so. He shouted: “In the name of the decent and loyal citizens of NSW, I declare this bridge open!”.

His protest was because Lang, not the Governor-General or indeed a member of the Royal Family, was performing the opening ceremony.

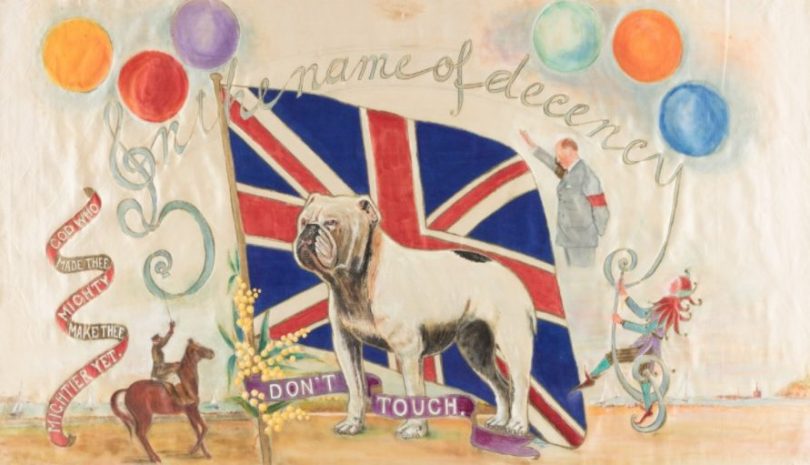

While many New Guard members felt the action was too radical, some who supported his actions presented de Groot with a hand-painted flag celebrating the incident; an idyllic image of the harbour forms the background, a bulldog in front of the Union Jack represents Britain, de Groot is shown on the left-hand side of the flag with his sword raised to slash the ribbon and an infamous photograph of Eric Campbell giving the Nazi salute, taken in December 1931, is reproduced in the top right.

A hand-painted flag was presented to de Groot by supportive members of the New Guard celebrating the Harbour Bridge incident. Image: Sydney Living Museums.

This flag was acquired by Sydney Living Museums in 2017.

Lang was dismissed by the governor in May 1932 and with the easing of tension, members of the New Guard melted away. Dissension grew among those remaining as Campbell grew more authoritarian and militant.

In 1933 he visited Europe and met Fascist leaders; the next year he published The New Road, a case for Fascism and Mussolini’s ‘corporate state’.

Campbell expanded on the group’s politics in a 1933 newspaper interview with The Herald (Melbourne): “We’re not Italian Fascists or German Nazis, but as far as the broad philosophy of Fascism goes I am a Fascist to my finger-tips”.

He tried to take the remnant of the guard into party politics, forming the Centre Movement, but was defeated for Lane Cove at the 1935 State election.

Years later, Campbell returned to “Billaboola” (then a part of “Memagong Station”) and continued to practise as a solicitor in Young, also serving as Burrangong Shire Council president from 1949-50.

His final years took him to Yass and then Canberra where he died in 1970, survived by his wife, two sons and two daughters.

Information and excerpts sourced from the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Living Museums Sydney and The Australian War Memorial.