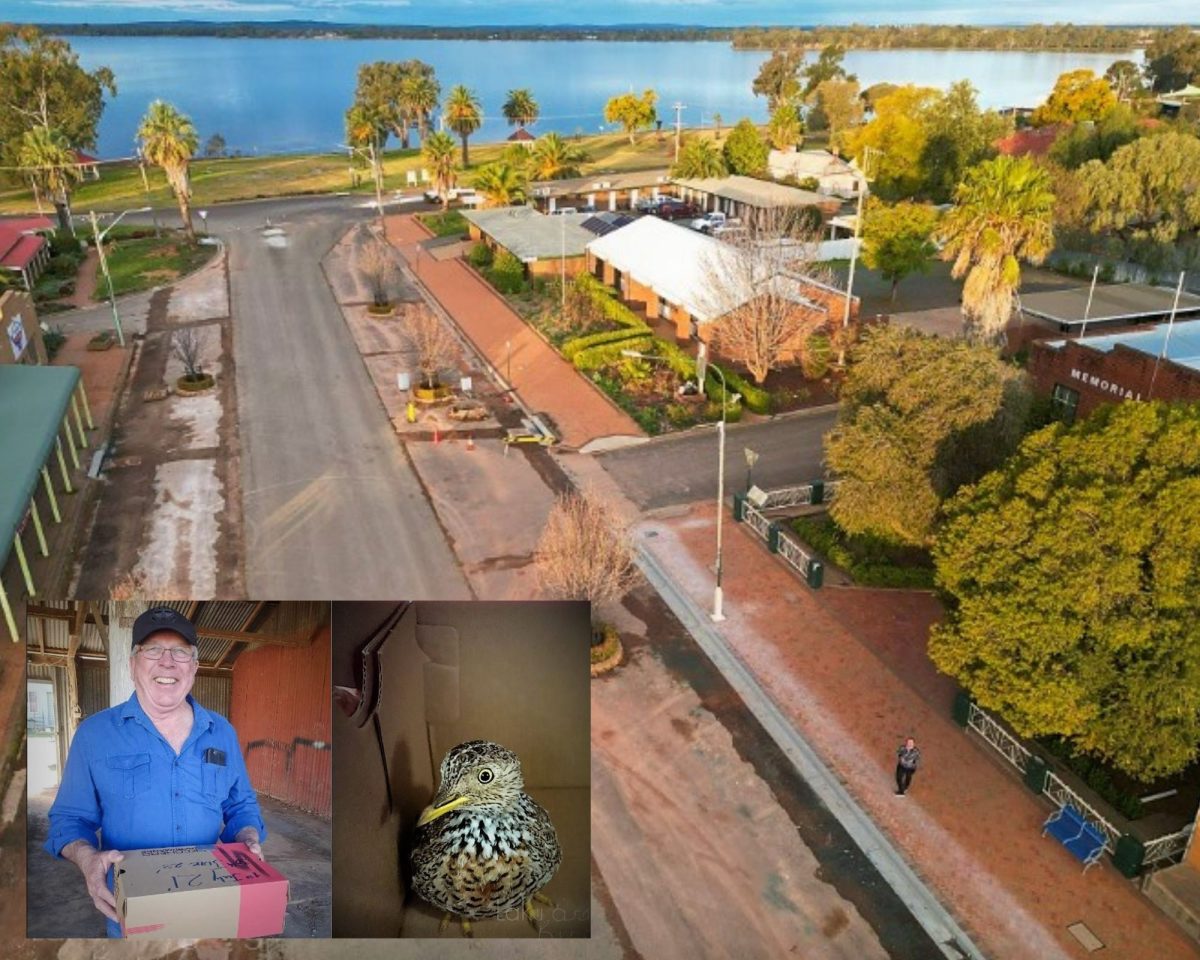

Found on the main street of Lake Cargelligo by Neil Hart and his grandson Harper, the rare plains-wanderer was swiftly rescued and is now safely housed at Taronga Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo. Images: Bec Van Dyke.

Space junk may be falling from the sky, China’s sun bears might be suffering an identity crisis, but nothing compares to what recently turned up in Lake Cargelligo.

The small northern Riverina town of about 1400 people was minding its own business when an unusual quail-like bird was spotted squatting on the main street by Harper Hart, grandson of local, Neil Hart.

Not just any bird – but a very rare, on the brink of extinction species of bird, way too far from its regular stomping ground.

His interest piqued, Neil took photos and sent them to the Lake Cargelligo Birds Facebook page administrator before relocating the bird to the far safer confines of a nearby garden.

That administrator, Bec Van Dyke, said her jaw dropped when she saw the photos; the tiny bird, astonishingly, was a plains-wanderer.

“Well, it looked like a plains-wanderer but,” she said, “that would be extraordinary given its location. No way would such a rare and special bird be found on the pavement in the busiest street of town.”

Bec immediately deferred to the Bush Heritage Australia website which revealed the plains-wanderer was, “critically endangered and at risk of imminent extinction”.

The small ground dwelling bird resembles a quail but they have lankier yellow legs and a yellow bill.

Native to southeastern Australia with small, fragmented populations in Western Victoria, eastern South Australia and the Western Riverina region of NSW, they prefer semi-arid, treeless, short native grasslands with 50 per cent bare ground on red-brown soils.

Bec said the locals immediately leapt into action.

Bec and Steve Van Dyke on one of their many bird photography expeditions. Image: Bec Van Dyke.

“When we realised the bird was so rare and in a risky location, with predators [dogs and cats] and cars close by, Neil was able to capture it again and put it in a safe, quiet, secure place. We then started the process of figuring out what to do with this special individual,” Bec explained.

News of the find travelled fast.

One of the first people to contact Bec was David Parker of the NSW Department of Planning and Environment (DPE) who is involved in the plains-wanderer conservation breeding program at Taronga Western Plains Zoo.

This project is part of a National Recovery Plan which aims to establish a population in purpose-built aviaries in the zoo’s sanctuaries with the goal of reintroducing them back into the wild.

“The program has seen successful releases in the past onto private properties in the Western Riverine near Hay where landholders receive support to manage their ground cover for both livestock production and plains-wanderer conservation,” Bec said.

“It’s a project that is a massive team effort of co-ordination, care and planning.”

Bec said the bird, which Neil named Lettie, after his granddaughter, was immediately transported to Dubbo, checked over by vets and, after a few days in an acclimation box, is now part of that program.

The sighting came just weeks after another rare species of bird – the Australian bustard – was also discovered in the region.

Bec said it was bird number 220 in their Lake Cargelligo bird count.

A large ground dwelling bird measuring up to one metre in height – Bec said it was like a mini emu.

Found mostly in open country, despite its wide distribution across Australia, the bustard is less common and mostly extinct in the southeast.

“We thought there would be no chance of ever seeing a bustard, that it was just a bird of the past but again we were proven wrong,” Bec said.

She and her husband Sandy purchased a lakefront property at Curlew Waters, one of the three lakes in the Lake Cargelligo system.

“At the time, we had no idea what the property would mean for us and how it would change us,” she said.

But in 2017, “a cool looking bird that looked like a duck with something weird on its back” caught their attention.

“Wanting to know what the weird thing was – I ran up to the house to find my camera, used the camera lens as binoculars and as I zoomed in I was gobsmacked because there were five tiny babies tucked into the feathers on its parent’s back,” Bec said.

“They were literally using their parent as a boat!”

The great crested grebes kicked off the Van Dyke’s bird photography journey. They chronicle their findings on social media, with 5700 Facebook followers, 812 on Instagram, and now there’s a website.

“We always hoped to eventually see 220 different birds, locally,” Bec said. “I say hoped because we thought it would take a lifetime to see such a variety.”

The plains-wanderer takes their count to 222.

“I say it often and I will say it again: you just never know what is going to turn up or where. I now officially believe in the unbelievable. Also, it is so important to take a little bit of notice and to care, our birds depend on it.

“Once you start to look deep into ecosystems it becomes quite magic really, and you realise that there is much more than first meets the eye in the places you are walking into,” Bec said.