Veteran journalist Ron Norton remembers the Cowra breakout as if it were yesterday. Photo: Michelle Kroll.

Little did Ron Norton know that in the early hours of 5 August 1944, he would be witnessing history – or that such observations would play such an important role in the rest of his working life.

A young schoolboy at the time, Ron, now 93, had just arrived at Cowra Railway Station with the Cowra High School rugby league and athletics teams. They had been in Young, competing in the sports carnival. Ron is believed to be the last surviving member of the group.

“It was about 2:40 am. I remember that because, although it was so late, there were lights everywhere and we heard all these sirens,” Ron explains.

“We later found out they were searchlights, but we didn’t know what they were at the time.

“I remember getting off the train and when the sirens went off, it prompted one of our team members to say, ‘Wow, there’s a big party going on at the POW camp tonight’.”

He couldn’t have been more wrong.

Ron, who became a journalist, was watching about 800 Japanese prisoners of war escape from the Cowra compound – Australia’s largest and bloodiest prison escape.

“Another reason I’ll never forget that night was because my brother was on the train with me,” Ron says.

“We had to go and pick up our bikes at the station and then ride the six miles home.

“I remember him saying to me, ‘Let’s go over to the camp to see what’s going on’. I knew Mum would kill us if we did that so we ended up going straight home.”

Even though it’s almost 78 years to the day since the Japanese broke out of the Cowra POW camp, it’s as fresh in Ron’s mind today as it was all those years ago.

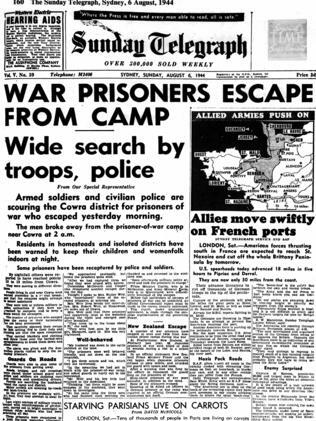

On page one, The Sunday Telegraph of 6 August 1944 reported that “residents in homesteads and outlying districts are being warned to keep their children and womenfolk indoors at night”.

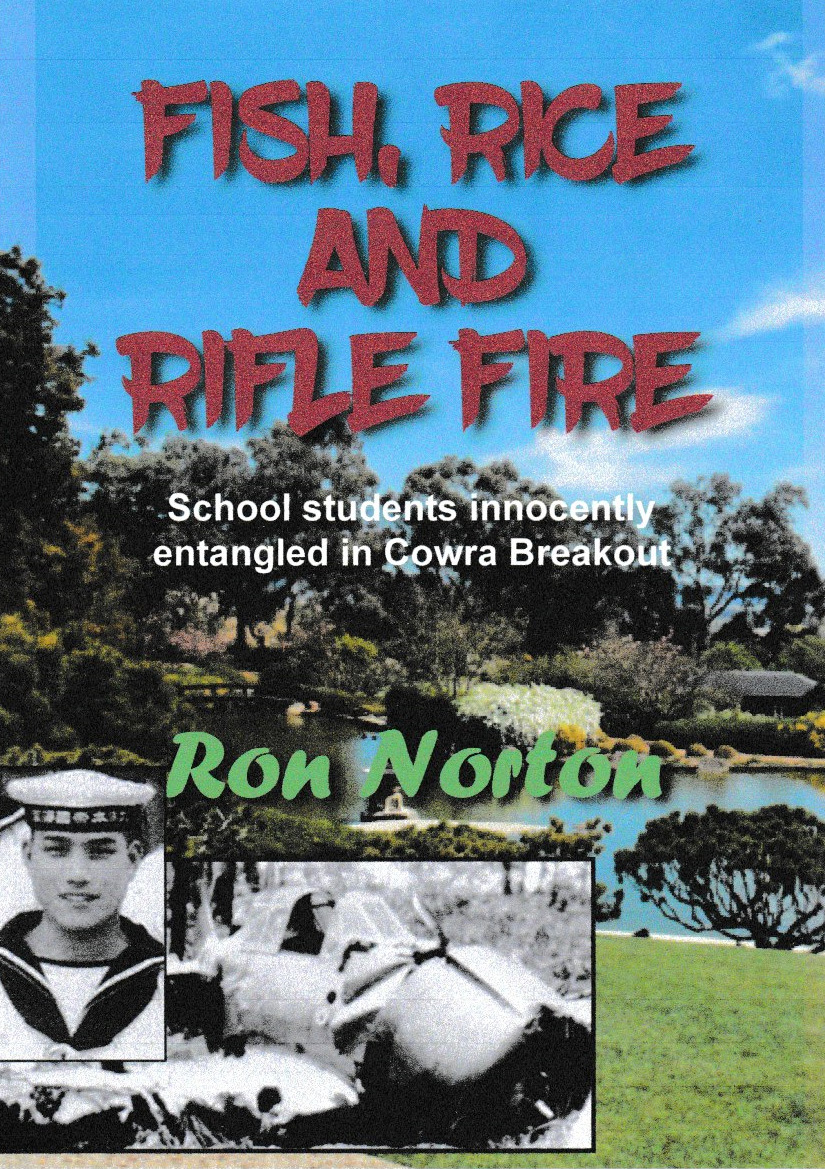

Ron Norton has written many words about the Cowra breakout, including this book, Fish, Rice and Rifle Fire. Photo: Supplied.

The Cowra breakout has been part of the veteran newspaperman’s life he’ll never forget, having written a multitude of stories of the event, what led up to it, and its lasting consequences.

He said stories abound about the breakout. How for the Japanese to be incarcerated was tantamount to being dishonoured. How so many of them gave false names when captured so their families at home would assume them dead – a more honourable fate in their eyes than being held as a prisoner of war.

Records show that for the Japanese, any escape plan meant they had to get over the hill nearest the camp. They thought if they got over that, they’d be OK because they would only have another hill to climb to reach the ocean. What they didn’t know was that the ocean was still more than 300 km away.

Under an agreed escape plan, the incapacitated prisoners would commit suicide to save face while the others would stage a mass escape, setting fire to the huts as they went. A bugle blast at 2 am announced the escape.

The Sunday Telegraph’s front-page headline from 6 August 1944. Photo: The Australian War Memorial.

Throughout his working life, the Cowra breakout has never been far from his mind. He has self-published a number of books about the event as well as writing stories for newspapers.

One of the highlights, he recalls, was while working at the Cowra Guardian when he interviewed district coroner Fred Arnold who presided over the inquest into the mass deaths. Details of the inquest were kept quiet for many years because there were fears of reprisals against Australian prisoners in Japan.

Official figures today show that 231 Japanese soldiers and officers were killed in the breakout, with 107 wounded. Four Australians also died: Lieutenant Harry Doncaster and privates Benjamin Gower Hardy, Ralph Jones and Charles Henry Shepherd. Hardy and Jones posthumously received the George Cross, an award for gallantry equal to the Victoria Cross.

About a year after the breakout, Ron said another journalist wanted to see the huts and how the prisoners lived. Even though they had been burned down, they did find some remnants, including a still.

“They must have used it for making saki with potato peelings. God know what it tasted like.”

The next year, he became a journalist, working at the Cowra Guardian, before moving on to other newspapers around NSW before settling in the ACT in 1969 and working on many of the capital’s newspapers of the time.

Aptly, on Canberra Day, 10 March 2019, Ron celebrated his 90th birthday and 50th year in Canberra with a family reunion of 99 direct descendants.

Today, as he looks towards his 94th year, he’s still writing.

Original Article published by Sally Hopman on Riotact.