Newspaper headlines from October 1950 captured the horror at Burrinjuck Dam, where nine workers were swept to their deaths in the swollen Murrumbidgee River. Image: Trove.

Seventy-five years ago, on 19 October 1950, Burrinjuck Dam became the scene of one of the state’s worst industrial accidents.

Nine men – including three from Monteagle, near Young – were killed when a timber platform above the southern spillway collapsed, hurling them into the raging Murrumbidgee River below.

The men had been performing a familiar but dangerous task: removing the 12-foot wooden “needles” that controlled the flow of water through the spillway.

After a night of heavy rain, the river was running high and the pressure against the dam walls was fierce.

Around 11 am, as one of the needles was being lifted by an overhead hoist and it jammed under the platform.

The structure tilted, splintered, and within seconds, nine men were thrown 250 feet into the gorge and swept to their deaths.

Government medical officer Dr R.A.G. Holmes later told an inquest the impact, “was at least equal to two cars meeting head-on at high speed”.

The men had died instantly from severe head injuries.

Those who perished were ex-serviceman Frederick Rule, 48; Frederick Basham, 36, a father of two; and James Chant, 33, a father of four – all from the small village of Monteagle near Young.

Also lost were Frank Barton, 22, from Leeton; English immigrants Reginald Lippiatt, 41, a World War II veteran, and Robert Elliott, 23; Romanian-born Eugen Podusteanu, 35, a married former statistician who had migrated only months earlier; Peteris Steinmanis, 35, a married Latvian factory worker who had arrived in Australia 15 months earlier with his wife and child; and James Fillery, 19, a single dogman from Rankins Springs.

Eighteen-year-old Bruce Grieves of Yass narrowly escaped the same fate.

One step from the platform, he paused and shifted his weight – a hesitation that saved his life.

“I was right there,” he later told reporters. “If I’d taken one more step, I’d have gone with them.”

The aftermath of the accident was grim.

More than 300 workers and police scoured the swollen river, setting up nets downstream as far as Jugiong, 30 miles away.

Eight bodies were eventually recovered; the youngest victim, 19-year-old Fillery, was never found.

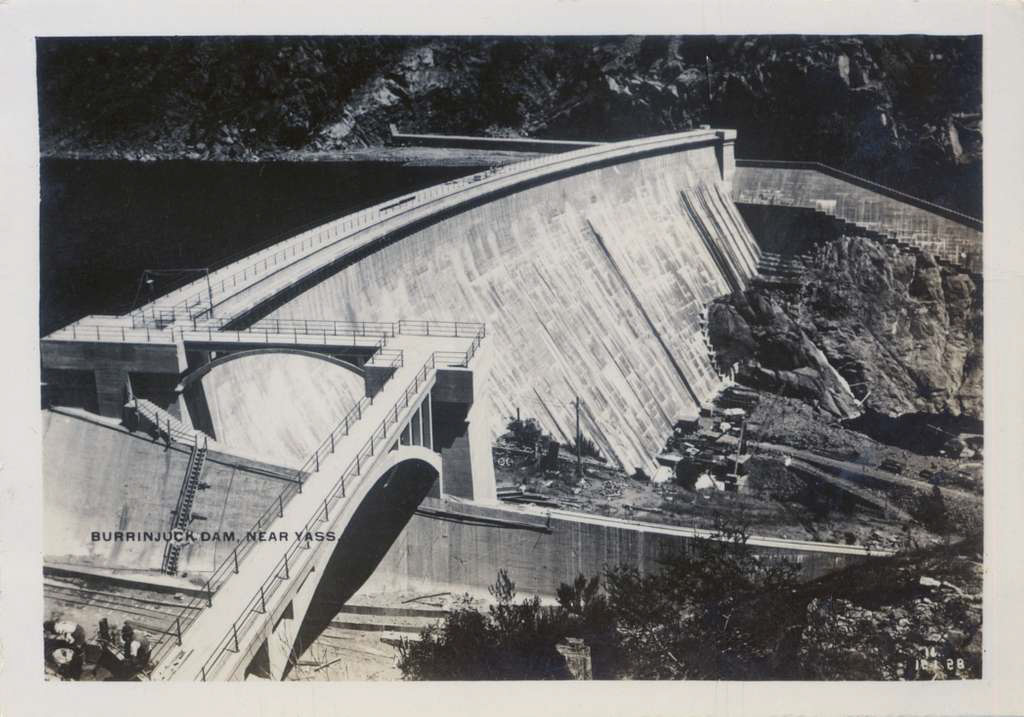

Postcard depicting Burrinjuck Dam circa 1948. Image: Royal Australian Historical Society.

The dead represented a cross-section of post-war Australia: locals, returned servicemen and new migrants chasing opportunity in a rebuilding nation.

Podusteanu, a refugee from Romania, had arrived in Australia just four months earlier, intent on saving his money to bring his parents out from Germany.

In an extraordinary act of solidarity following Podusteanu’s death, his workmates would donate their wages to ensure his parents could still make the journey.

Support for the bereaved families came swiftly. The Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) launched a fund for the widows and children, while Burrinjuck workers pledged to raise £1200 in additional aid. In Yass, townspeople organised collections to help the families until official compensation was arranged.

For Burrinjuck, tragedy was not new. The dam – an engineering marvel of its era – had long carried a toll in lives lost.

During its construction, four men died on site: Patrick McNamara in 1908, David Knox in 1914, Bernard Cullen in 1916, and ganger Edward Miller in 1924.

The 1950 accident, however, struck with particular force.

The three-day inquest ruled the deaths accidental but exposed the dangers of manual dam work and the limited safety standards of the time.

Testimony revealed that fateful day marked the first time a cableway – a type of travelling crane which moves on a cable from one side of the Burrinjuck gorge, to the other – was used to pull needles. Previously the needles had been removed by hand or released automatically.

Evidence indeed suggested a wooden needle, one of two being lifted by the hoist, may have jammed beneath the platform, forming a hook that triggered its collapse.

Assistant engineer Calder Edward Oliver testified that incorrect use of the overhead sling could have caused the disaster.

Foreman Ken Davis told the inquiry the men had moved the hoist from the position he had designated – about 15 feet out from the platform – to directly above the needles.

Yass district coroner E.H. Hickey found the platform had been weakened by decay and stressed by the rising water, yet the men were sent to work regardless.

He recommended the Water Conservation and Irrigation Commission prepare detailed safety procedures for removing the needles, to be reviewed by the AWU.

The AWU later instructed its solicitors to issue writs against the Minister for Conservation, seeking £60,000 in damages on behalf of the dependents of the nine victims.

Widows were eventually awarded compensation through these proceedings – a rare early example of successful union-led industrial action over workplace safety.

In the years that followed, the Burrinjuck disaster became a turning point for dam maintenance practices in NSW.

Written safety protocols were introduced for all spillway work, including the use of harnesses and mechanical supports for lifting operations.

By the mid-1950s, the Water Conservation and Irrigation Commission had formalised risk procedures that became a model for similar sites across the state.

Today, Burrinjuck Dam remains a vital part of regional infrastructure – regulating the Murrumbidgee, powering irrigation and hydroelectricity – but its concrete walls also herald a human story.

The names of Frederick Rule, Frederick Basham, James Chant, Frank Barton, Reginald Lippiatt, Robert Elliott, Eugen Podusteanu, Peteris Steinmanis and James Fillery endure as a reminder of the courage of working men and the heavy price paid for progress.

* With thanks to the Yass and District Historical Society for their original post reminding us of this anniversary.