Before and after: the old Burrangong Hotel at Young has been painstakingly restored to its late-1800s glory. Photo: Suez Hardy.

For 161 years, dishevelled pockmarked banks have characterised the creekscapes of Young, artifacts of the town’s foundational gold rush provenance.

They’re the lonely survivors of those days of bark slab huts and calico tents, when miners – up to 9000 of them within the first months of gold discovery – greedily ripped through the gold-bearing soil.

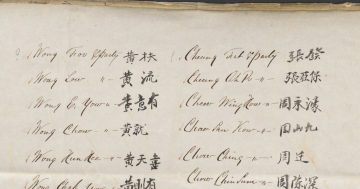

Out at Blackguard Gully, east of Young, where the Chinese diligently mined, the diggings are well indicated, allowing tourists to imagine what life was like at Lambing Flat in the 1860s, a town branded wilder than the wild west.

Blackguard Gully is embedded in Australia’s history as the site of one of the nation’s worst riots against Chinese miners.

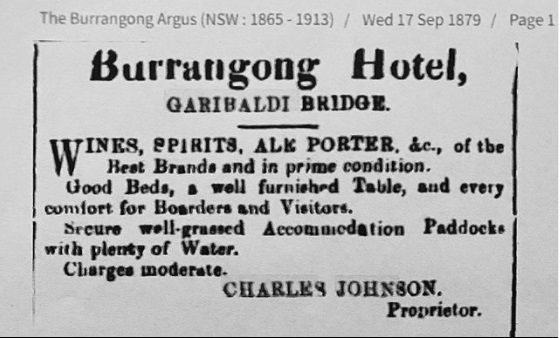

In 1879, the Burrangong Hotel offered the full suite of comforts for the weary, and thirsty, traveller. Photo: Trove.

Across the road, an abandoned, overgrown and dilapidated red brick and granite building stood almost invisibly, disregarded by passers-by on one of the town’s busiest thoroughfares since the settlement took root along Burrangong Creek.

But recently, it seemed fitting that a baby shower was held within its four walls, as this relic of past – now restored to its 1800s glory – celebrated its own rebirth.

For Susan Hardy, known to all as Suez, and her builder son, Sam, the timing could not have been more serendipitous. She’d had this project on her mind for 20 years since she and her husband, Craig, bought the block.

Happenstance in the form of COVID-19 allowed Sam time to focus on the project during a year in which he and his partner, Bella, received the news they are expecting their first child, due in early 2022.

So as the champagne and sandwiches were passed around, the once popular watering hole – relieved of 150 years of encumbrances – breathed again.

Through advertisements in The Burrangong Argus, Suez can trace its lineage at least back to the early 1870s.

“We’re still researching, but I think it was a house that was turned into a pub in 1874,” she says.

Suez Hardy and her son, Sam, share a celebratory drink at the restored Burrangong Hotel. Photo: Suez Hardy.

Sam’s great-uncle had his first drink at Burrangong Hotel before it closed in 1922, returning to use for occupation, serving as a rental and listlessly decaying at the mercy of vandals.

Suez clapped eyes on it and snapped it up two decades ago, enduring decades of taunts from her family who suspected she was on the edge of insanity.

Damaged to the degree that heritage specialists said it was beyond redemption – with walls and chimneys kicked down, floorboards pulled up, fallen ceilings and home to a variety of rodents and plant species – the old house appeared unsalvageable.

But Suez, with the gift of seeing diamonds in the rough and a talent for turning copper, cutlery and coffee pods into jewellery, saw way more.

“I’m sort of that little magpie that sees something shiny or old and gives it a new life,” she says.

However, time almost knocked that idea on its head.

“We sat and waited and when Sam found a spot in his calendar, I guess we decided now is the time to have a go at restoring her,” says Suez.

“We just changed the timber and put a new roof on it, and tied it in a little better so it looked like it was, with a few modern touches.”

Which is a massive understatement.

Inch by inch they cleared, cleaned, scraped, sanded, researched, restored and rebuilt the seven-room building.

Followers of the property’s Instagram page have been treated to months of updates and little finds that tell stories which appear to predate Suez’s time estimates.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CS1eHaSnQow/

Mud-covered, hand-moulded, heart-etched convict bricks – dating back to the 1830s – were among the discoveries, as were the salt-block-bag lined walls, broken ceramics, tiny brown bottles, layers of wallpaper, aged fruit trees underplanted with heritage garlic, and an 1898 penny that dropped from the architraves.

Embedded in the wall was a piece of magnesite picked up by Peter Hughes as he cleared timber near Thuddungra at just 17 years of age. His grandson, the late Vic Hughes, said in 1935 three sons started mining the magnesite using a pick, shovel and wheelbarrow.

A far cry from the crater that is Causmag’s mine in Young today.

As the property was being resuscitated, there was one rule Suez was committed to – staying as close to its built purpose as possible, using old techniques and natural finishes.

Convict bricks were among the many treasured finds during the restoration of the Burrangong Hotel. Photo: Suez Hardy.

“We’ve stayed true to its heritage, recycling whatever we could from the building or from town,” she says.

“The walls are curved and they have pot bellies, they’re not straight, which was really tough on Sam who is used to straight lines.”

Today the old brick pub is looking like a gleaming gold nugget, which Suez hopes will lure even more visitors to the town.

It’s currently fascinating the oldies, all with stories to tell of the old building, gifting Suez things they’ve held onto for years.

“There’s an 87-year-old man who lives out Boorowa way and he can recall as a child standing outside and being given a flag, and he wants to bring that flag back,” says Suez.

“I love the history of Young. It is so rich, and I want to see more people come here and experience that.

“Ideally, this will work as an Airbnb for two people, but I want to see the rest of the place used by the community, with a donation to charity.

“Even though it’s our property, I feel like it [is also] the Young community’s. The town needs to have ownership and love this place like we do.”