Assistant Commissioner Justine Gough heads up the AFP’s Cyber Crime Command. Photo: Claire Fenwicke.

A cybercrime was reported to the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) every eight minutes in Australia last financial year – and this number was expected to continue to grow.

In response to the growing threat, the AFP established a stand-alone Cyber Command based in Canberra at the start of the year to tackle the problem.

Heading up the command is Assistant Commissioner Justine Gough.

“It’s really in response to the threatening environment we find ourselves in,” she said.

“Cybercrime was determined as one of five crime priorities for the AFP in 2020. It’s quite significant as cyber was always part of a broader crime family before that.”

The Cyber Command focused on cyber-dependent crime, such as illegally modifying electronic data, spreading malware and ransomware.

“It’s basically crimes that didn’t exist before computers,” AC Gough explained.

Her Command also liaises with other resources combating cyber threats, such as the ACSC, which is based in the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD). The Joint Policing Cybercrime Coordination Centre (JPC3) fell under the Cyber Command.

AC Gough said this collaboration could help identify cybercrime that might be overlooked in isolation.

“[Say there’s a scam], the amounts of each individual crime may not be classed as large-scale fraud … but together, it could suggest a syndicate targeting Australia for money,” she said.

“One example is business email compromise, which is where the bank details in a [statement or invoice] email are altered … when the monies are paid, they instead go directly to criminal groups.

“Or someone poses as an executive of a business, asking for money to be transferred. It looks legitimate, but these are often spoofed emails.”

AFP officers undertake digital forensics during a search warrant. Photo: AFP Media.

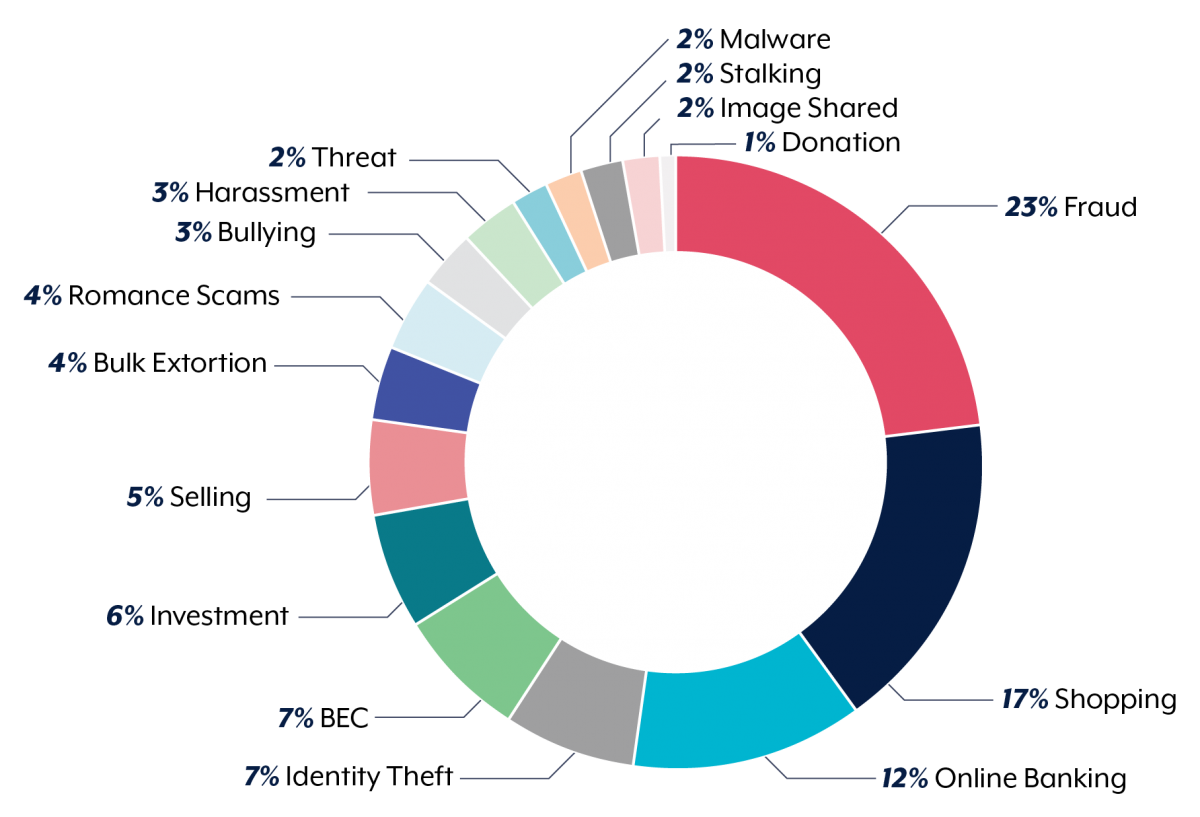

In the 2020/2021 financial year, 67,500 reports were made to the ACSC ReportCyber portal, an increase of 13 per cent on the previous period.

This equated to one report every eight minutes, “but that’s trending to about one report every five minutes”, AC Gough said.

The unit has had some big wins recently, including the arrest of a now 24-year-old Melbourne man who was 15 years old when he allegedly created a Remote Access Trojan (RAT) program which could then be remotely installed on a victim’s computer.

This allowed the buyers to control a victim’s computer, steal their personal information, or spy on them by remotely turning on their webcams and microphones without their knowledge.

Operation Cepheus found 201 people in Australia had bought the tool, including a large number of domestic violence offenders and one registered child sex offender. It was sold to 124 countries and has had at least 14,500 purchases.

“We’ve alleged this was purchased for very, very dangerous reasons,” AC Gough said.

AFP digital forensics officers capture evidence as part of a search warrant. Photo: AFP Media.

Another bust was through Operation Genmaicha, which investigated an SMS phishing campaign that was targeting users of Australia’s major banks.

“Victims would receive a text message saying their online banking had been locked and invited them to click a link and enter their bank information,” AC Gough said.

“This puts their personal information directly into the hands of criminal syndicate members … their bank accounts were soon depleted and their identities compromised.”

The investigation found 20 million text messages – a “conservative estimate” – had been sent.

AC Gough said that while many Australians had lost money because of the scam, people underestimated the psychological impact.

“It’s rage, the sense of violation, people feel stupid, it’s a range of different emotions … people are quite psychologically damaged by cybercrime,” she said.

Two men were sentenced in June for their roles in developing and distributing the technology.

Cybercrime reports by type for the 2020–21 financial year. Photo: Australian Cyber Security Centre.

The Command was also looking into future tactics to disrupt and prevent cyber crimes in Australia.

It was made up of a multidisciplinary team of specialist techs, police officers and intelligence officers and also had information exchanges with the FBI, Europol and Interpol.

AC Gough said wherever they saw a crime emerging, they worked to combine resources to tackle it efficiently and effectively.

“We’re asking ourselves, how could a criminal go about hacking or accessing technology? How could they modify it? What codes could be used?” she said.

“It just shows the pivot towards the technological sophistication necessary for policing in the 21st century.”

She also focused on ways to upskill local police investigating cyber crimes.

“We need to ensure our entire workforce is upskilled, that their digital literacy and knowledge increases,” AC Gough said.

“There’s a cyber-related element to most crimes these days, such as online fraud, data encryption on a drug dealer’s phone, illicit goods traded on the dark web.

“Police are generalists and are expected to be able to investigate everything.”

AC Gough said it was also important for people to be aware of how to protect themselves from cybercrime.

“Just as you lock your doors and windows, you should secure your electronic devices and information,” she said.

“Be very cautious of giving out personal information via text, email or phone calls … so many of the scams that exist are very clever, they really prey on the vulnerabilities of a person, and in a lot of cases, they are tailored directly to their victims, especially if they’ve put a lot of details of themselves online.”

People were encouraged to contact the ACSC if they believed they were a victim of cybercrime.

“This also allows us to define areas of priority to focus on … if we see a particular cluster of a fraud or scam, we can divide resources to focus on it,” AC Gough said.

“There are some cases where people who have worked very hard have had their savings depleted.

“It’s not fair and it’s not right.”

Original Article published by Claire Fenwicke on Riotact.