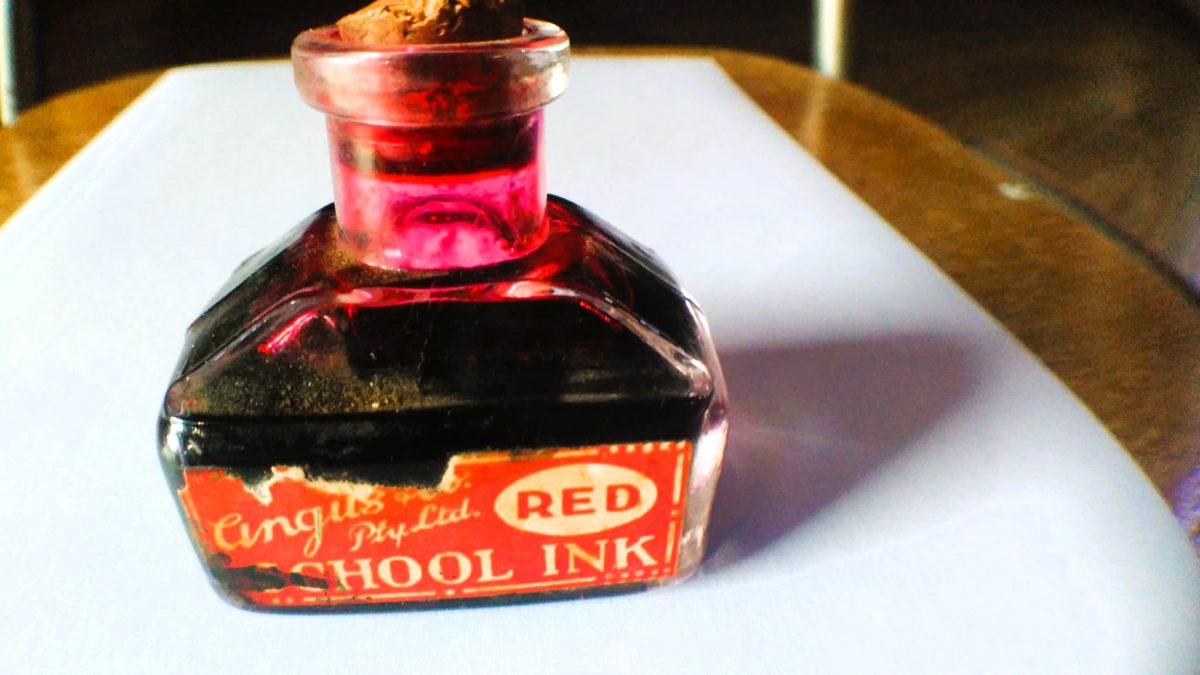

An Angus and Co ink bottle at the museum which, says curator Bruce Wicks, is a rare circa 1890 find with label attached and full of red school ink. Photo: Bruce Wicks.

In the heart of Gundagai’s main street, inside the towering walls of the old 1881 Assembly Hall, is a museum unlike any other in Australia – possibly the world.

There are no velvet ropes or polished security screens but inside, time stands still.

Beneath quiet rafters and the smell of old wood and older paper, more than 3800 artifacts tell the story of human connection through the simple, elegant tool of the pen.

It all started with a teacher.

“It was 1958 and I was seven years old and given a dip pen by my teacher Mrs Ranyard,” said Bruce Wicks, founder and sole curator of the Australian Pen Museum.

“She was on the point of retirement and gave our class a try with it,” he said. “I was too young to be using a dip pen and did not understand at the time why we were allowed to take the pen home but I can remember her comment as she looked at my scrawl: ‘It looks like a spider ran over that’”.

That 1958 schoolroom moment in rural Australia left an indelible mark and while Bruce forgot about the pen for a while – he rediscovered it in a back verandah cupboard at 19 and asked his mother for it.

“Mum said it was mine anyway, so I thought I should get an ink well to go with it. Thirty years later, I finally did. Meantime I collected everything associated with pens,” he said.

The Australian Pen Museum is Bruce Wicks’ life work – part obsession, part tribute and entirely a labour of love.

The museum overflows with not just pens but centuries of history: Roman bronze styluses from 2000 years ago, Victorian desk sets, writing desks, hand-cut nibs and even a 400-year-old parchment document.

There’s also a meticulously reconstructed schoolroom frozen in time, “as if the students stood up a hundred years ago and just walked out”, Bruce said.

The centrepiece? Possibly a rare Waterman doll pen from 1910 – “fewer than 10 are believed to exist”.

Or there’s the 1905 handcrafted dip pen crafted from Tasmanian tiger myrtle.

The latter, Bruce said, was fashioned by a bushman for an American couple who’d come to Tasmania to photograph insects. Embedded in its shaft is a tiny lead map of Tasmania.

Then there’s the Roman stylus: “bronze, functional, and 2000 years old,” he said, “used to write into clay tablets. That’s real permanence.”

The museum contains a meticulously reconstructed schoolroom frozen in time. Photo: Bruce Wicks.

Unlike most museums, this one is run entirely solo.

Bruce lives on-site and opens the doors seven days a week, from 8 am to 8 pm – and later in the warmer months.

He hasn’t just collected pens. He’s built a reputation.

“Many visitors are so taken by what they see, they send pens or writing items afterward,” he said, “and we never sell, trade or dispose of anything given to the museum. That’s a promise.”

A dedicated honour roll lists every donor, many of whom passed away before seeing the museum completed.

“They trusted me, and I’ll remember them until eternity.”

Each artifact is authenticated either through museum contacts or historical publications.

Ancient items are bought only from museums with duplicates, while more modern pieces are assessed using Bruce’s growing expertise – honed over 66 years of collecting.

“I wasn’t a spectacular hand writer myself,” Bruce said, “as I also had an interest in aviation and obtained my student pilot licence at 16 requiring log entry.”

To call it a pen museum is, in some ways, misleading.

Wicks’ collection charts not just writing tools but the evolution of how we express, document and define ourselves.

From school desks to government seals, from copperplate calligraphy to wartime correspondence, and from ornate inkwells to ink-stained blotters and hand-drawn maps, every shelf and drawer carries a trace of someone’s thoughts once laid down in ink.

“People are shocked by numbers and the variety of artifacts,” Bruce said.

“They don’t realise how central writing instruments have been to daily life. Until they see it.”

His dedication has turned Gundagai into an unlikely pilgrimage site for handwriting enthusiasts, antique lovers, historians and curious travellers – some of whom simply stumble in while stretching their legs after detouring off the nearby Hume Highway.

The museum doesn’t rely on grants or a volunteer army.

It runs on one man’s commitment, open heart, and extraordinary sense of memory.

While pens are slowly disappearing from desks and classrooms, in Gundagai, they’ll be preserved – one nib, one story at a time.

For more information on The Australian Pen Museum visit its Facebook page.

Footnote: for those among you who don’t know what a dip pen is (I had to ask). A dip pen has to be inserted into an ink well; it writes about a line before it has to be re-dipped as against a fountain pen that has a built-in reservoir which only needs refilling after a number of pages writing.