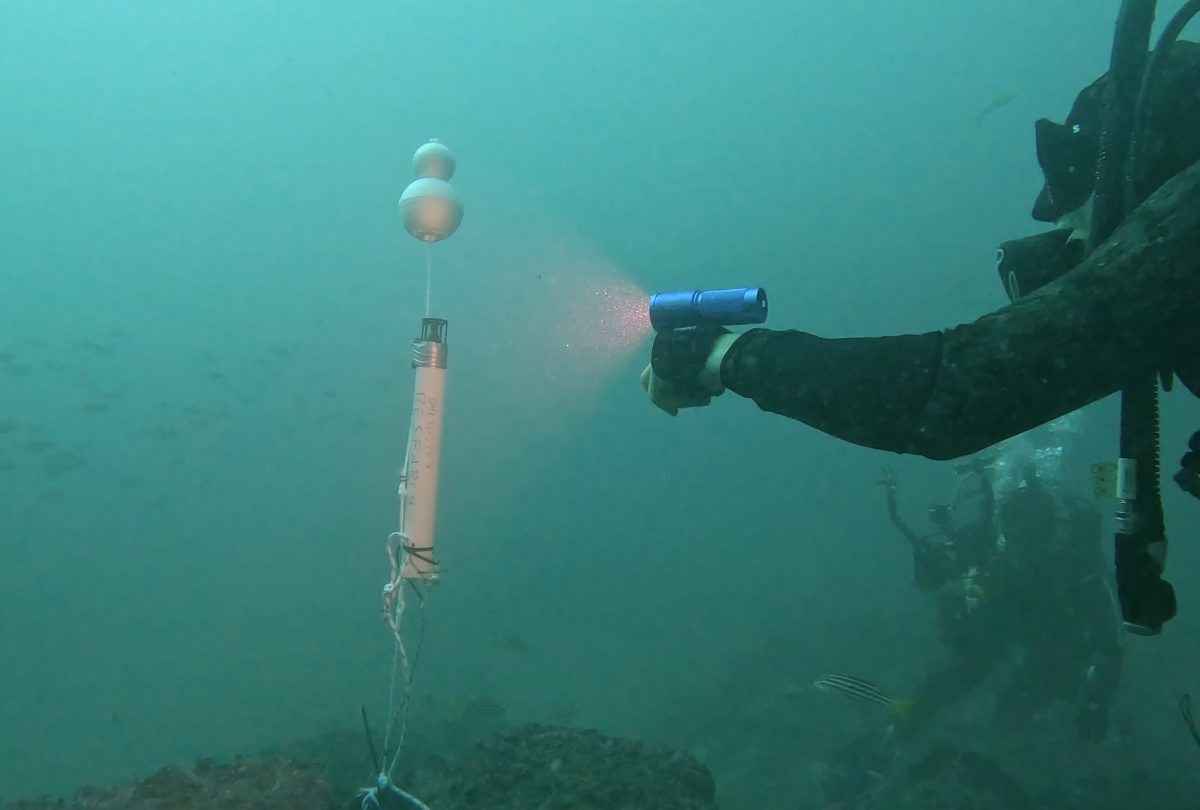

Several hydrophones have been stationed off the Australian coast, helping researchers learn more about how whale migrations are changing. Photo: Olaf Meynecke.

When she’s out on the diving boat, Tammy Bellette can hear whales during their migration – and through an ongoing study, she’s helping researchers do the same.

The Batemans Bay local runs diving business and tourism operator Beneath the Bay with her husband Michael.

“You may not be able to see them, but you can always hear the whales when they’re passing,” she tells Region.

“As long as they’re talking to each other and having a sing-along, you’ll hear them from most of our dive sites.

“You will often see them on our surface intervals – the divers will get to see the whales passing by as well.”

In 2024, the pair were asked to install a hydrophone (a recording device that works underwater) to help track the mammals’ migration past their coastal town.

A second was installed the following year.

It’s all part of an ongoing study involving researchers from Griffith University.

One of those involved is Doctor Olaf Meynecke, manager of the university’s Whales and Climate Program.

Batemans Bay is the most southerly location the researchers are examining.

Other devices have been set up in places such as Sydney, Cairns and Lady Elliot Island.

Doctor Meynecke says each location is carefully chosen to give researchers the best chance of recording whale songs.

“They [local dive operators] help us find a reliable location … in terms of currents and waves and accessibility.

“Most people might not know, but deploying any kind of instrument in the ocean is extremely difficult.

“If you want to go any deeper than the standard diving depths, it gets quite tricky because you have to find a way to retrieve the instrument and also ensure it has enough weight so it doesn’t move.”

Once the devices are installed, it’s a waiting game.

Each device’s battery runs for about six months – collecting the sounds of underwater life – and (most importantly) whale songs – before being retrieved by the dive operators.

“It stores all the data – that’s why it’s so important to get it back!”

Researchers say the recordings indicate whale migrations are changing, with more staying in southern waters. Photo: Olaf Meynecke.

A combination of an algorithm and “manual labour” is then used as they sort through the recordings.

“This round generated, at least, seven to eight terabytes of data. It’s going to be a lot of files to go through – it’s already a storage issue,” Dr Meynecke says.

“We go through displaying the different software, which means you can see the sound as an image. We’re trying to extract the ones that we haven’t heard before, [meaning] the frequencies that are now.”

As they identify which ones are humpback whale songs, a more rounded picture of the whales’ presence in coastal waters develops.

Doctor Meynecke believes there’s been a shift in the mammals’ migration patterns, with whales leaving for their migration earlier as ice melts and some of the whales staying off the South Coast (compared to their counterparts further north).

“There is definitely a bit of an increase in presence, even in August, but there’s still a clear, distinct difference between the northern and southern migration.

“We haven’t got that on the South Coast – it just has whales all the time.”

He says these early results are echoed in people seeing more whales (and earlier in the season), but that isn’t a complete picture.

“We can’t do long-term visual sighting surveys, so we’re often missing the fine adjustments the whales are undertaking to mitigate and adapt to climate change,” he says.

“What we’re interested in seeing is shifts in migration timing and if there’s any shifts in their presence and absence.”

He also says it’s too early to confirm what is driving the changes (and further rounds of their study are still to be completed), but believes it’s down to a combination of factors.

“They might have been doing this, 30 to 40 years ago, when there were just not too many whales. … But back in the days when there were only a few thousand whales, everyone probably moved up north,” he says.

“Now, when there’s more whales, more can stay behind, save that energy and wait for the breeders to come back during the southern migration.”