Canberra author Karen Viggers, at home with her dog. Photo: Zhensi van der Klooster.

Canberra author Karen Viggers is probably as surprised as anyone about how she went from being a suburban veterinarian to selling 800,000 copies of her last novel in France.

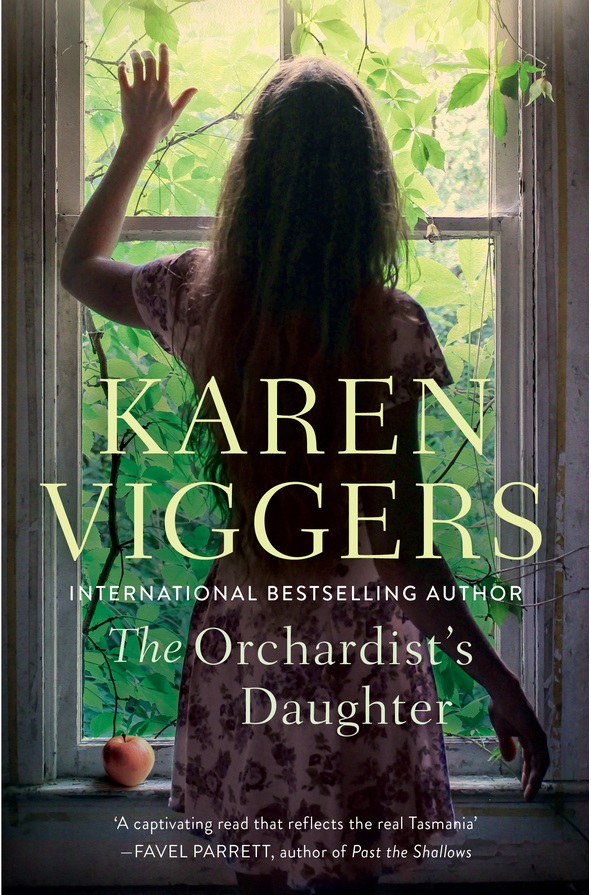

“That’s like every single person in Canberra having two copies of The Lightkeeper’s Wife,” she laughs. Sales exploded after a French publisher championed the book, set on Bruny Island. In her new novel, released this week, Viggers returns to the Tasmanian wilderness to look at nature, human relationships and the tensions of facing change.

The Orchardists Daughter is set in a logging community. Miki was a homeschooled child whose brother, Kurt, keeps her closely guarded after their parents’ tragic deaths. Leon, who also appeared in The Lightkeepers Wife, is a parks ranger. Miki and Leon are both outsiders with a shared passion for the disappearing Tasmanian devils, wedgetail eagles and the threatened forests. The story is set against conflict over logging and conservation.

Viggers has a passionate connection with the island state. “I love that long gentle soft light, the wilderness, the mountains. I would move there tomorrow,” she says. Visiting Bruny Island before a stint in Antarctica as a volunteer veterinarian, “I saw the steely grey southern ocean rolling in, and knew that the next place was the land of ice. You could feel the breath of the ice on the wind.”

Wilderness has always been important: her husband is wildlife ecologist David Lindenmayer who has fought to save endangered forest species. But Viggers says that in all her books, she likes to hover above an issue and try to understand differing motivations.

“Because of my background as a vet, I have a passion for wildlife and a fascination with wilderness. In this book, the Tasmanian devils and wedge tails eagles are symbols of freedom that are very pertinent to Miki’s situation.

“But I’m also interested in the impact of change on timber communities, the pressures they feel. You go to those parts of southern Tasmania and sure, they are touristy, but there’s also a lot of poverty and that’s why it feels like another world. You see cottages in cold wet places with walls of wood on the fences, curls of smoke rising up.”

In the novel, Miki’s parents retreated to keep their family safe but she realises after their death how isolated she’s been and struggles to reconnect.

Viggers had observed friends who homeschooled their children after the eldest was bullied at school. A religious family, they became more so as they withdrew further. Viggers saw in the three teenagers a mounting need to connect with the outside world.

“They knew no other children their age, they had no internet, they saw only hand-picked movies. You could feel resentment and I wondered what those children would say if they were given a voice. That rolled into Miki, and how it might feel to be in that situation and pave your own way to freedom,” she says.

Viggers says her French audience enjoys the kind of “meaty, challenging contemporary realist literature” she writes, but also wild landscapes and stories about rural life. After the huge success of The Lightkeeper’s Wife, she spent a year there, brushing up on her schoolgirl French (and making the odd error along the way).

“I wanted to be able to speak to the locals, and I used to say ‘Je suis excite’ about the book’s success…until I realised that means being excited in a very different way!”

Ideas can be slow to gestate – the new book took five years. Research includes returning to “ground truth” a location. “I don’t like to labour descriptions, but I like a reader to be able to feel it, to smell it, to sense it. To stand in the forest and feel the bark slapping against the trunks and the rustle of the canopy, the cracks as a branch goes down.”

The draft writing process takes around six months – the “fun part” – and then it’s drafting and redrafting, “anywhere between six and sixty times”. Sometimes progress simply stops: Viggers has 300 pages of a novel sitting on a shelf, a process she describes as ideas germinating then composting. The Orchardist’s Daughter went through a wholesale rewrite that she believes has given it strength and heart.

But for now, book events are planned around the country including Tasmania. And whatever idea pops up through the compost next will likely involve wild places.

“We can be so isolated from nature in big cities that we forget what amazing untouched places we have by comparison with the rest of the world. I’m trying to remind people that those places exist and that if they care about them, they need to connect with them and save them.”

The Orchardist’s Daughter is published by Allen & Unwin and is available online and in bookstores.

Original Article published by Genevieve Jacobs on The RiotACT.