The Friends’ maternal grandparents, John and Evelyn Brown, grew up at “Thornleigh”, Parkesbourne, in a home that has succumbed to time and the elements. Photo: Neville Friend.

Sister and brother Joyce Hall and Neville Friend grew up in Parkesbourne, west of Goulburn, in the 1950s amid stories of their ancestors’ hardships in slab huts with dirt floors and Sir Henry Parkes’s vision of utopia.

Parkes had championed more equal access to property ownership in the 1860s and the Friends’ ancestors and their neighbours obliged. Many of those settlers had come from Parkesbourne, an area overlooked by the pioneering Chisholm family due to a lack of water.

Joyce and Neville’s father, Bert, was one of a family of 10 children who emulated his father’s enterprise in buying blocks of land, including at nearby Mut Mut Billy village.

Neville worked for Bert until 1988 and then took over the property.

As a boy, he loved going out from their home at Parkesbourne to the farm on the weekend.

“I developed a passion for railways. Dad was very interested in trains and I took on the same interest,” he said.

“We were travelling along the Breadalbane Plain one day and Dad, usually a pokey driver, all of a sudden sped up and when we got to Breadalbane I found out why – there was a Beyer-Garrett [steam locomotive] going through.

“One of our farm blocks is next to the railway line, so we had to cross the line to get to Mut Mut Billy. They have automatic signals there today, of course, but when I was a kid they had gatekeepers there. You had to stop at the gate, blow the horn and they’d come out and unlock the gate, let you through and lock the gate behind you.”

So accurate was Bert with any sort of firearm, Neville reckons he could have competed at the highest level.

“Dad was a fantastic shot with the shotgun. I remember as a kid, I’d throw a tin can up into the air and Dad had an air rifle and would hit it every single time,” he said.

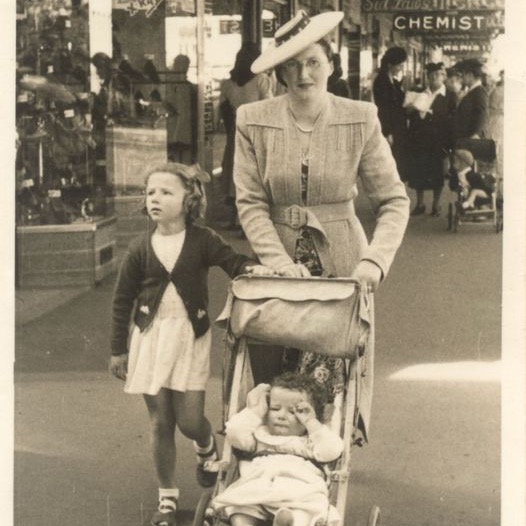

Margorie Friend with her daughter Joyce and son Ray in the stroller in Goulburn’s main street about 1948. Photo: Friend family collection.

Each Wednesday – ”Town Day” – Joyce and Neville’s mother, Marjorie, would be elegantly dressed.

“Dad would go to the sheep sale and Mum would run around doing all the shopping,” Neville said.

On her list were the two main department stores, Rogers and Knowlmans, and the biggest grocer in town, Moran & Cato.

Joyce said: “I remember back in ration days, Mum would take her ration card to Moran & Cato, sit down and give the grocer her order and he would be taking things off the shelves. Things like tea and butter were still being rationed.”

The family lived at “Thornleigh”, a 50-acre (20-hectare) block with a home that belonged to their mother’s family, handed down from her parents and grandparents.

Before the arrival of electricity in 1957, their father bought Marjorie a petrol iron, which terrified her.

“He would have to light the iron for Mum before he went out to the paddocks because Mum wasn’t even game to light this petrol-run iron,” Joyce said.

In this Methodist community, Bert Friend was frowned on for working on the farm on a Sunday.

“It was a very religious community. We used to call it the Holy City,” Neville said, laughing. “There is still a strong church (community) going out there.”

Good behaviour mattered at the one-teacher school too, where Joyce and Neville can recall two teachers on separate occasions falling asleep. Joyce said when their teacher, John Richards, nodded off, the older pupils organised the younger ones with their lessons and let him sleep.

“Steve Ball did the same thing,” Neville said. “There would be a line of kids saying ‘Sir!’, ‘Sir!’, and Steve Ball would be sound asleep. He also had a nursery business and I think he used the school to catch up on his sleep.”

Moving to a boarding hostel, St Margaret’s at the top of Verner and Cowper streets in Goulburn and run by the Anglican Church for her high school years, Joyce did not escape discipline.

Joyce Hall and Neville Friend remember everyone having orchards at Parkesbourne, austere Methodists and lots of fun as children. Photo: John Thistleton.

“At the beginning of the year, they read out a couple of foolscap pages of rules, such as you will not leave the premises without permission; you will not wash or iron on a Sunday; no whistling,” she said. “I think I managed to break every rule except one – I never did get around to ironing on a Sunday.”

Neville left Parkesbourne in 1974 when he married. Joyce left the boarding hostel and moved to Canberra, where she joined the Commonwealth Public Service. Remnants of slab huts, a couple of little Uniting churches and scattered farmhouses are all that’s left of Henry Parkes’ dreams.