After many years working with a wider range of colours and specialising in restoration projects, painter and decorator Greg O’Neill says off-white and whites blend in with most colours and black never dates. Photo: John Thistleton.

A bewildering choice of colours and finishes were yet to find their way into the hands of professional painters when Greg O’Neill began his apprenticeship in Goulburn in the late 1970s.

He began with a five-inch bristle brush on a picket fence in the days of oil-based colours coming in little more choices than white and mission brown.

In no time he was climbing ladders. Up three storeys one day looking over the rooftops and hills across Goulburn, Greg balanced on the end of a triple extension, 40-foot ladder painting the gable of Conolly’s Mill.

“I had no fear of heights back then,” he said. “We had never heard of cherry pickers (boom lift); we had no harnesses. It was an experience; it was ‘don’t look down’, you just kept your head up.”

Apprenticed to John Dalsanto, he learned from his boss, his older brother Brian who steered him into the trade and Robert Antelmi among others. Their experience coupled with a four-year course in painting and decorating gave him a thorough grounding, covering wallpapering, decorative finishes and glazing windows.

“It was part of our trade to replace windows,” he said. “Any putty that was falling out, we used to reglaze it, put the beveled edge back on it,” he said.

Painters reeked of turps, the only thing able to clean oil-based paint off them.

“The paint would splatter, not like the paint these days, the acrylic just hangs in there,” he said. “You used to cover yourself in that splatter.”

Peter Wharton working on the coat of arms at Goulburn Court House, a job Greg O’Neill won through a Public Workers tender. Photo: O’Neill family collection.

Nevertheless, working with Dalsanto’s team on places like St Clair villa and Bishopthorpe, built for the first Anglican bishop of the Goulburn Diocese, Greg developed an enduring appreciation for the city’s exceptional heritage buildings.

As the market slowed Greg left the team and found work at the Railway Per Way workshops where he spent 10 years, then several more on the signal branch, painting the upper quadrants (arms) of rail signals, from Wallendbeen down to Glenlee near Campbelltown and signal boxes at Demondrille, Harden with another Goulburn painter, Kevin Painter.

In the late 1980s then premier Nick Greiner’s ‘razor gang’ began slashing jobs; Greg was reassigned to working on railway lines, out of his trade.

“I was keen to stay in my trade and started my own business in the early 1990s,” he said. Forming a partnership with his wife Deb, he worked on his own until enough jobs came his way to employ more painters. The O’Neills’ two sons Bayden and Nathan became Greg’s apprentices. Their daughter Alleesha also helped with odd jobs.

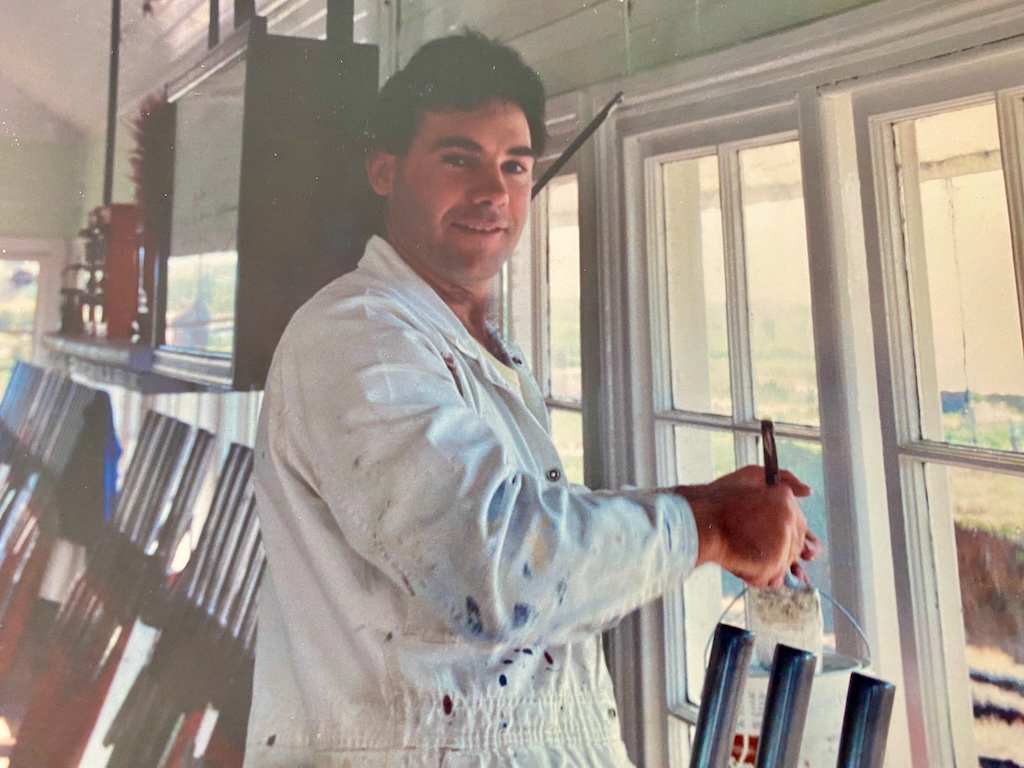

Greg O’Neill painting inside the railway signal box at Demondrille siding, near Harden. Photo: O’Neill family collection.

Nathan now has his own painting business in Goulburn, as does Bayden on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast.

Look closer at some of Goulburn’s outstanding heritage buildings and you will find the hand of Greg there. He has painted the Mechanics Institute in the city’s main street four times, including for one-time owner Geoff Martin. “He was a town planner in Sydney and had a good eye for colours and we have had favourable remarks over the years,” he said.

With the help of Tony Gooden, Greg replaced just about every window in an abandoned and vandalised barracks for train drivers. A group of Goulburn artists subsequently converted the barracks into “Gallery on Track’’.

“We pulled out the old canite ceiling and found the original truss ceiling which was magnificent,” Greg said. The trusses have remained a distinctive feature ever since.

He has painted grand homesteads including Merrilla station and South Rareburn, main street facades, Gunning Court House and an unusual job repainting the coat of arms at Goulburn Court House. “We had to find gold leaf on the lettering, silver paint to match it, bright blues and reds,” he said.

Heritage-type work in the 1990s was completed in only a handful of choices: Brunswick green, deep Brunswick green, Indian red or Dulux creams.

He has engaged other craftsmen to help on projects, including Roger Doughty, who replaced timber finials on prominent homes and other rooftop features on federation homes.

Painters Brian O’Neill, John Booker and Greg O’Neill working on Gunning Court House. Photo: O’Neill family collection.

In recent years he has noticed oil-based enamels, which have always yellowed over time, are going off more quickly. “I think that’s because they don’t put enough titanium in the paint anymore and are pushing towards water-based enamels,” he said. “The water-based enamels don’t yellow off like the old enamels do, they stay more brilliant white.”

Unlike those early paints, his appreciation of heritage has never faded.