First officer Paul Clyde Hudson, flight engineer Rick A DeMorgan Jr and Captain Ian H McBeth were killed when their large air tanker crashed near Adaminaby. Photo: Coulson Aviation.

Hazardous weather conditions, poor communication, and a lack of policies and procedures around cancelling high-risk firefighting tasks were contributing factors in the deaths of three US firefighters near Adaminaby during the Black Summer bushfires, according to the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB).

Captain Ian McBeth, first officer Paul Clyde Hudson and flight engineer Rick A DeMorgan Jr were killed when their Lockheed C-130 large air tanker crashed on 23 January 2020.

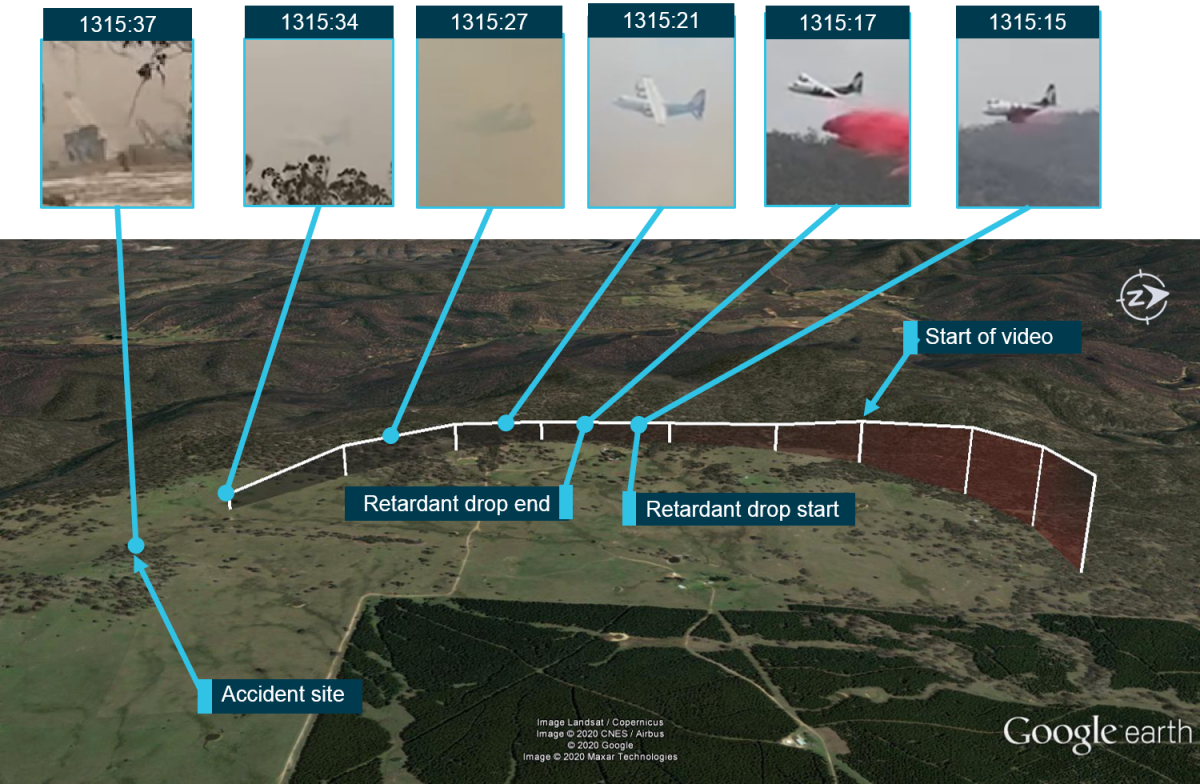

The ATSB investigation found the aircraft likely “aerodynamically stalled” in hazardous weather conditions after dropping retardant on the Good Good Fire near Peak View. Those conditions included strong gusting winds, wind shear (which abruptly changes an aircraft’s flight path) and an increasing tailwind.

The fire and local terrain likely exacerbated these conditions.

Images show the aircraft’s altitude and approximate flight path at key times. Images: Google Earth, witness videos and Skytrac data annotated by the ATSB

On the morning of the incident, the Rural Fire Service (RFS) State Operations Centre had tasked two large air tankers to conduct retardant drops at Adaminaby – a Boeing 737 and the C-130.

The 737 departed from the RAAF Richmond Base first and dropped its retardant at about 12:25 pm. The pilot in command reported conditions were “horrible down there” and advised the pilot assigned to guide large tanker aircraft across fire grounds in the area (known as a ‘bird dog’) – “don’t send anybody and we’re not going back”.

The pilot in command also let the airbase manager know they would not go back to Adaminaby as the “winds were getting too strong and the visibility is down”.

The bird dog pilot reviewed the weather and declined the tasking to assist aircraft in the Adaminaby area. Smaller fire-control aircraft had also been recalled.

The assessments by the bird dog pilot were not communicated to the C-130 crew by the RFS.

According to the ATSB report, “when the bird dog pilot rejected the tasking, based on operational safety concerns, there was an expectation from them and the operator’s pilots that the tasking for the LATs [large air tankers] would be cancelled, or at least reconsidered”.

“In this case, the crew were not provided with a full awareness of the situation, with no knowledge of the bird dog pilot rejection or that smaller fire-control aircraft were no longer flying.”

There was no RFS policy that required this information to be passed on.

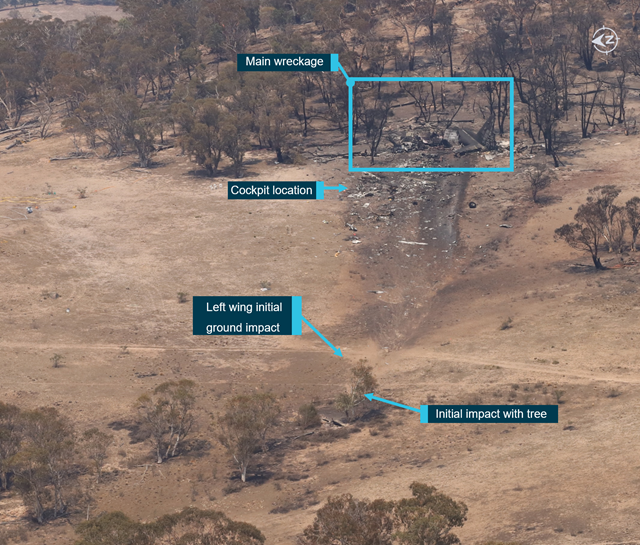

Accident site overview showing the wreckage trail. Photo: ATSB

It was decided the C-130 crew would be tasked to head to the Adaminaby fire ground to make the “decision of safety of bombing operations” and whether additional aerial operations would proceed.

The ATSB report stated appropriate policies and procedures regarding task rejection should have cancelled the orders for the C-130 to head to Adaminaby.

“There were two opportunities for this. The first was at the time of the bird dog rejection when [the C-130] was departing Richmond which, at the very least (noting the RFS understanding of differing capabilities between the bird dog and the LATs) should have resulted in communication of that information to allow the LAT pilots to make their own more informed risk assessment,” it said.

“The second was when [the C-130] was transiting over the Canberra region and the RFS received advice from [the Boeing 737] which indicated that it was not suitable for LAT operations.”

While en route, the American crew spoke with the returning Boeing 737. They discussed the conditions on the ground and that the Boeing wasn’t heading back. When the C-130 crew arrived at Adaminaby, they experienced similar hazardous weather conditions and decided to accept an alternative tasking to the nearby Good Good fire ground.

It crashed at about 1:15 pm, shortly after dropping retardant on the area.

Hazardous weather conditions and a lack of appropriate warning devices on the aircraft were also found to be contributing factors to the crash.

The report noted wind shear was a known phenomenon that could be exacerbated by fire-associated winds that may be difficult to forecast.

However, the C-130 was not fitted with any wind shear warning systems, which were not available at the time of manufacture.

“In the absence of an airborne system, wind-shear detection is reliant on the pilot’s assessment of the conditions based on the information available and their interpretation of that information,” the ATSB report said.

The aircraft’s audio recorder was not recording at the time, so it was unknown whether the crew had been aware their aircraft was being impacted by wind shear in the seconds before the crash.

Main aircraft wreckage components. Photo: ATSB.

In the wake of the report, ATSB Chief Commissioner Angus Mitchell said the crew’s decision to accept the taskings at the fire ground was consistent with aircraft operator Coulson Aviation’s practices.

“The investigation found that Coulson Aviation’s safety risk management processes did not adequately manage the risks associated with large air tanker operations, in that there were no operational risk assessments conducted or risk register maintained,” he said.

“In addition, the operator did not provide a pre-flight risk assessment tool for their firefighting large air tanker crews. This would provide predefined criteria to ensure consistent and objective decision-making with accepting or rejecting tasks, and would take into account elements such as crew status, the operating environment, aircraft condition, and external pressures and factors.”

Coulson Aviation has since introduced a pre-flight risk assessment tool, a new three-tiered risk management approach and wind shear procedures and training.

Separately, the investigation found the RFS had limited large air tanker policies and procedures for aerial supervision requirements, no procedures for deployment without aerial supervision, nothing in place to manage task rejections, and no policy or procedures to communicate this information internally or to other pilots working in the same area of operation.

“The responsibility for the safety of aerial firefighting operations has to be shared between the tasking agency and the aircraft operator,” Mr Mitchell said.

“This accident highlights the importance of having effective risk management processes, supported by robust operating procedures and training to support that shared responsibility.”

RFS Commissioner Rob Rogers said the service was committed to implementing measures to address the ATSB’s recommendations and concerns.

“Work is already underway to put systems and processes in place, including improving notifications to pilots,” he said.

“Key policy changes will be implemented prior to the coming bushfire season, as will the establishment of a manual process for notifying pilots when others have rejected taskings to conditions.

“Some of the improvements and systems changes are complex and potentially have national implications. We will continue to work with the ATSB, contractors and other organisations to ensure we not only minimise the risk as much as possible but also ensure firefighting operations are effective and timely.”

Original Article published by Claire Fenwicke on Riotact.