Port Jackson shark eggs are often found on South Coast beaches. Photo: The Shark Trust.

Many have a smooth, simple appearance, others have ridges or curling tendrils that anchor them to kelp or coral, and some are shaped like a corkscrew.

They’re often found washed up on our coastline, leaving beachgoers guessing.

They are shark or skate egg cases, and South Coast residents are invited to help track them down.

In the lead up to Easter, what better time for The Shark Trust to launch its Great Eggcase Hunt in Australia?

In partnership with the CSIRO, the trust is calling on citizen scientists to find and record egg cases washed up around the Australian coastline or those seen by divers.

The Great Eggcase Hunt is suitable for all ages and everyone from the occasional beachgoer to seasoned beachcombers and even divers can get involved.

Some sharks and true skates lay egg cases, also called ‘mermaid’s purses’, which are tough, leathery capsules that protect an embryo that develops inside. After several months a fully formed juvenile will emerge and the discarded cases can often be found along the strandline, among the seaweed.

Recording the location of egg cases enables researchers to identify species presence and diversity.

The Great Eggcase Hunt, an initiative of United Kingdom-based charity The Shark Trust, will provide new data for scientists studying the taxonomy and distribution of oviparous chondrichthyans.

CSIRO Australian National Fish Collection biologist Helen O’Neill said recording sightings of egg cases on beaches and coastlines would help scientists discover what the egg cases of different chondrichthyans look like, with some species still unknown.

“Egg cases are important for understanding the basic biology of oviparous chondrichthyans, as well as revealing valuable information such as where different species live and where their nurseries are located,” Ms O’Neill said.

Senior conservation officer at The Shark Trust Cat Gordon said the Great Eggcase Hunt began in the United Kingdom 20 years ago and had since recorded more than 380,000 individual egg cases from around the world.

“We’re really excited to be partnering with CSIRO to officially launch this citizen science project in Australia and to be able to expand the Shark Trust’s egg case identification resources,” Ms Gordon added.

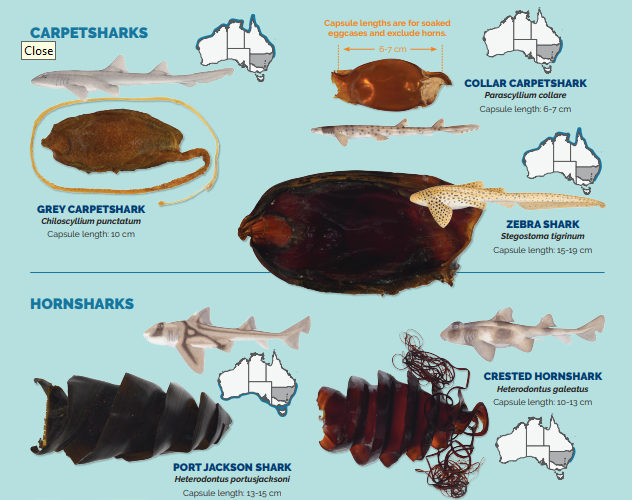

“There’s such a diversity of species to be found around the Australian coastline, and with a tailored identification guide created for each state, they really showcase the different catsharks, skate, horn sharks, carpet sharks and chimaera egg cases that can be found washed ashore or seen while diving.

Egg cases come in many different shapes and colours, ranging from cream and butterscotch to deep amber and black. They range in size from about four to 25 centimetres.

Each species’ egg case has a unique morphology that is helpful in taxonomy, the science of describing and naming species.

“At the Australian National Fish Collection, we are matching egg cases to the species that laid them,” Ms O’Neill said.

“We borrow egg cases from other collections, museums and aquariums around the world and use our own specimens collected from fish markets and surveys at sea or extracted from the ovaries of preserved specimens in our collection.”

Chondrichthyans have the most diverse reproduction strategies found among vertebrates, encompassing parthenogenesis (no father), multiple paternity (more than one father of the litter), adelphophagy (baby sharks predating each other in the womb) and various modes of egg laying.

Some of the egg cases found in New South Wales. Photo: The Shark Trust.

Egg cases found on beaches rarely contain live embryos, whose incubation times range from a few months up to three years, depending on the species.

“Egg cases found washed up on beaches have likely already hatched, died prematurely due to being washed ashore or been predated on by creatures like sea snails, who bore a hole in the egg case and suck out the contents,” Ms O’Neill said.

As well as documenting empty egg cases, the trust is keen to receive records of egg cases developing in-situ. Underwater records help pinpoint exactly where sharks and skates are laying and can be linked to beach records. Learning the depth and substrate that they lay on also helps us to better understand the species.

Divers, snorkellers and stand-up paddleboarders are being asked to keep an eye out. The eggs may contain a live shark or skate, so it’s important not to disturb them.

It’s hoped a new series of egg case identification guides will inspire people to get out and about in search of mermaid’s purses and that the project proves as popular in Australia as it does in Europe.

To get involved in the Great Eggcase Hunt, you can record sightings via the Shark Trust citizen science mobile phone app or through the project website.