The snow gum (eucalyptus pauciflora) is rapidly disappearing from Australia’s alpine landscapes. Photo: Supplied.

If there was a poet who perfectly captured the character of the magnificent, tortured snow gum, it was David Watt Ian Campbell.

This poet of the Monaro and man of the mountains was born to a farming family in 1915 at ‘Ellerslie Station’, near Adelong, in the Snowy Valleys region of NSW.

David Campbell stepped through life in big strides. While studying abroad at Cambridge University he represented England in rugby union, served with the RAAF during World War II, and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1943.

It was during RAAF missions when he began contributing poems to illustrious Australian magazine The Bulletin which laid the foundation for a literary body of work that remains prodigious today.

Campbell returned to the land, living and farming on three properties: ‘The Well Station’ at Gungahlin, ‘Palerang’ near Bungendore, and ‘The Run’ at Queanbeyan, his observations of the land influencing his works until his death in 1979.

Mullion Park in Gungahlin was named after Campbell’s book of poems, The Miracle of Mullion Hill, written when he lived at ‘The Well Station’.

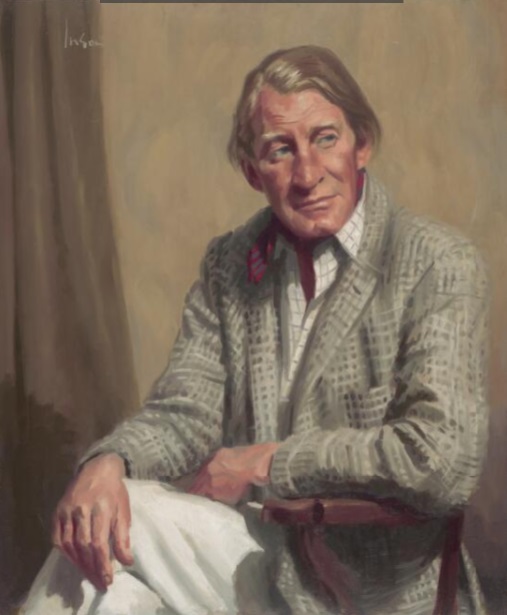

David Watt Ian Campbell (1915-1979), by Graeme Inson, c1964. Image: National Library of Australia.

The park honours him with these words: “Not for his work as a grazier, nor for his dedication to the Royal Australian Air Force, in which he served and was wounded as a pilot in World War II, but for his lyrical poetry about love, war and the Australian rural life.”

The park incorporates excerpts from his poems, embedded in wooden pedestals and on pathways. It is intended to connect residents to the heritage of the region and provide a cultural and recreational retreat.

A bust of Campbell can also be seen in Garema Place, in Canberra’s CBD, alongside fellow literaries Judith Arundell Wright and Alec Derwent Hope.

But while long may the poet live on in monumental form, his beloved snow gum (eucalyptus pauciflora) is rapidly disappearing.

The many people who have ventured to areas 1400-1600 metres above sea level in the alpine regions of southeast Australia – Kosciuszko National Park in NSW, Brindabella National Park and Namadgi National Park in the ACT, and Bogong High Plains in Victoria – will have marvelled at these ornate, smoothly contorted cenotaphs to toughness, tenacity and longevity, some of which can survive temperatures up to minus 23 degrees Celsius.

Their fate due to dieback has been widely documented with researchers joining the race to save the species from being eaten alive by infestation of the native woodboring longhorn (or longicorn) beetle, whose larvae eat the timber.

Starting with the crown, the canopy of affected trees gradually declines in health and dies. In most instances, infestation ends with the complete death of the tree, and in the most severe cases, an entire stand.

The cause of death in snow gums is easily determined by horizontal scars across the tree limbs.

An accelerated rate of death among the species is concerning scientists who, in a bid to isolate the environmental impacts, are grappling the challenges of geography in this rugged and remote part of Australia.

Researchers are turning to citizen science to help determine populations of snow gums throughout southeast Australia. Photo: Australian National University.

So they are turning to citizen science.

Jess Ward-Jones, a PhD student at the Australian National University (ANU) is part of a group researching dieback of snow gums, and is seeking the public’s help to develop records of snow gum populations across the entire alpine regions.

Developing a simple smartphone-based survey, Jess is asking anyone out and about to help determine locations and health of snow gum stands.

This data will be used to analyse the relationship between the trees’ landscape position and the likelihood of being affected by dieback.

“I’m not requesting a systematic survey, but rather observations made when they are convenient for you,” says Jess. “They should only take a couple of minutes at a time.”

The only special guidelines recommended for the survey are that the records are made around 1km apart within snow gum stands.

“However, more records at smaller intervals are also welcome,” says Jess.

She also says the more observations she has the better the analysis will be.

“This work, along with other research, will hopefully lead to positive management outcomes for these iconic trees,” says Jess.

The user-friendly snow gum dieback spotting app steps users through the survey, and provides descriptions and images to help identify snow gums and dieback symptoms.

The ArcGIS Survey123 is available for Apple and Android devices, or by following this link.