Artist Cheryl Davison with her installation that tells the story about Wonga and the waratahs. Photograph: David Rogers Photography.

Cheryl Davison describes her artwork as “innocent” – very simple, yet impactful, telling the stories of her ancestors and Country.

As part of Sculpture Bermagui, and in partnership with Four Winds and Bundanon, the celebrated Walbunja, Monaro artist spoke about her project Warigamban.

Meaning ‘a long time ago’ in the Dhurga language, Warigamban is a large-scale sculptural and screen print installation that brings stories of Country, cultural practice, and Dreamtime to life through immersive visuals.

Ms Davison chose the name because both works explore ancestral memories passed down from generation to generation through art and song.

Four Winds’ Windsong Pavilion was packed on 15 March (Saturday), the audience mesmerised as Ms Davison interwove Dreamtime stories while explaining the technical side of the artworks and dropping in pearls of knowledge and wisdom.

“When Bundanon asked me to do something on Country, I really wanted to honour the ancestors,” Ms Davison said. “There is no better way to tell their story than the cultural practice of bread making, which brought a lot of people together.”

Her people used the resources around them to make bread, notably the nuts from the vast burrawang forests.

First, they made baskets from lomandra or rushes growing out of the river.

Once made, the baskets were placed in the river while whole families went out collecting burrawang nuts.

The nuts were placed in the baskets in the running creek to wash away all the poisons. That took weeks.

Meantime, people lived off the land, fishing and hunting.

“If the burrawang nuts are ready, the fish start to come and nibble them,” Ms Davison said. “That is why it is important those little fish are not fished out.”

The nuts were ground into a flour and made into damper.

“People remembered how to treat burrawang because they were in songlines,” she said.

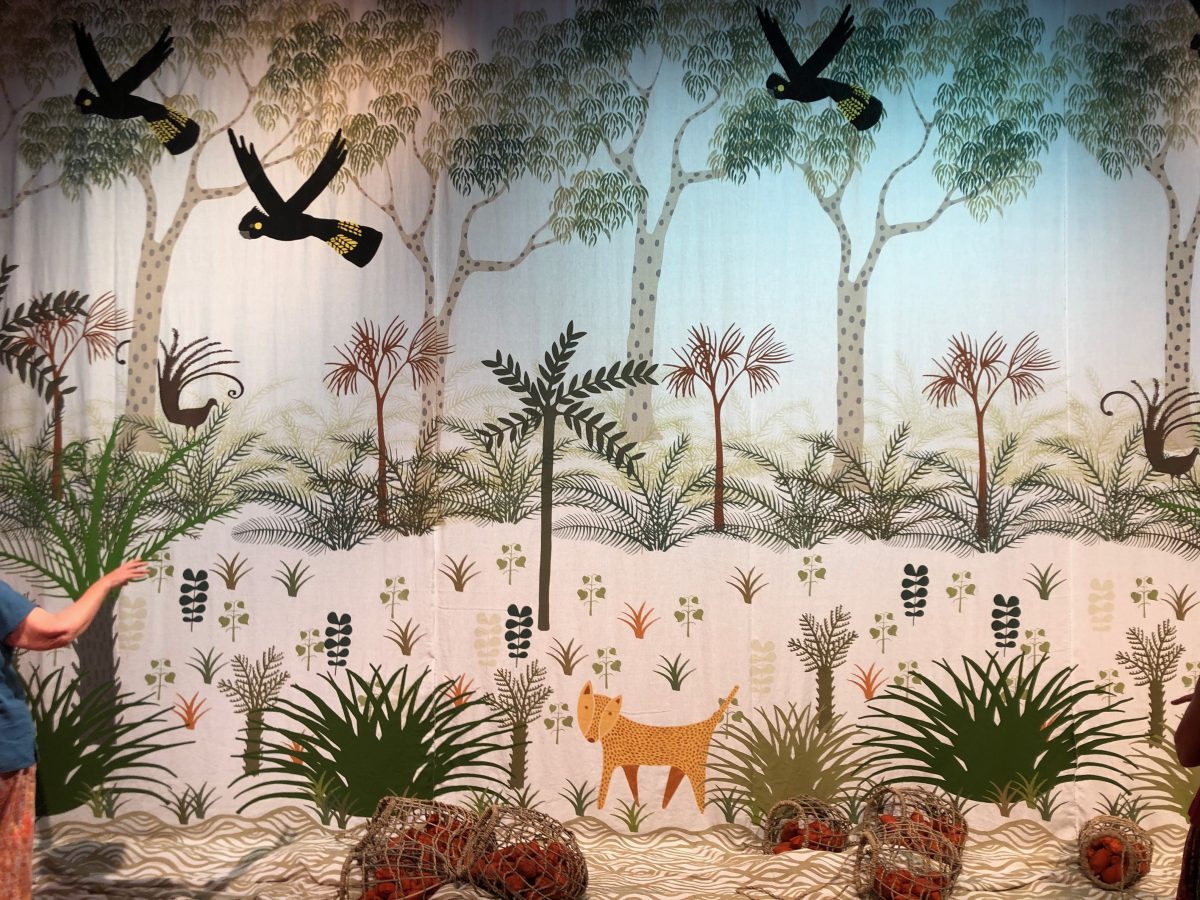

Cheryl Davison’s large-scale screen print about the cultural practice of bread making. Photo: Marion Williams.

The huge screen print began with the baskets and burrawang and evolved into showing the whole forest. The baskets were made by local artist Don Atkinson.

Everything in the screen print is there for a reason, from the fish in the creek and the baskets, to the incredibly life-like black cockatoos, and the dingo, which is part of Ms Davison’s lore. “That is my integrity, doing it right culturally.”

Ms Davison loves fabrics and dyes, and loves Country. “This piece speaks to the things I know.”

The screen print is made from very expensive pure Turkish linen which is three metres wide.

Basil Sellers Exhibition Centre in Moruya commissioned the other installation about Wonga and the waratahs some years earlier.

In the Dreamtime, waratahs were white. The installation tells the story of how the waratahs came to be red.

It revolves around Wonga, a mother pigeon waiting for her husband to return to the nest.

“We always tell our children to look at the practices of how animals care for their children,” Ms Davison said.

Detail from Cheryl Davison’s installation that tells the story of Wonga the pigeon and how waratahs came to be red. Photo: Sean Burke.

A group of women in Bermagui made the big mass of waratahs and the sticks were made by Mr Atkinson and his partner Jidi Cooper.

“The markings are our message sticks,” Ms Davison said. “That is how we communicated as well. It wasn’t all verbal.”

Ms Davison said sometimes her people might not know the complete story, just the main part.

For example, they have a story about a cockatoo that flew through smoke from a fire as he was heading west. While she was in Western Australia, Ms Davison learnt that the people there have a story about a cockatoo coming from the east.

The story of the seven sisters is another that spreads across a huge part of Australia.

“Elders from Central Australia will tell you a certain place has the most significance for that part of the story, so each story stretches,” she said.

“The other amazing thing about our stories is you can marry them up with science.”

The Yuin people’s story of Gulaga and her sons Barunguba and Najanuka is confirmed by science in that geologists found that Barunguba and Najanuka were born when Gulaga erupted millions of years ago. “We knew that,” Ms Davison said.