An active walker and prolific reader, Jan Collins remembers from her childhood accidentally disturbing bees while they sipped nectar from split pears, leaches in dams, and sweet, bowl-sized peaches weighing down branches in Charles Valley. Photo: John Thistleton.

One hot day in the early 1950s, Jan Collins climbed up a cherry tree in her parents’ orchard and ate her fill of ripe red fruit.

It was late spring in Charles Valley on the eastern side of Rocky Hill. Apple, pear and stone-fruit trees had spread out on either side of the valley since the 1800s, when orchardist and florist Thomas Charles, Jan’s great-grandfather, came from Nottingham, England, and began planting trees.

Cherry-stained Jan returned home so thirsty that day she had a big drink of water.

“I was so sick, I have never eaten a cherry since,” she said. “I hate cherries.”

Later, an exceptionally wet season wiped out the 20 or more cherry trees.

That experience aside, Jan grew up in idyllic surroundings.

“I was lucky, I had a lovely childhood,” she said, reflecting on the family’s large weatherboard home with a long hallway down the centre and a wood-fired fuel stove that turned out delicious lamb roasts on Sundays.

Poddy lambs, chooks and the odd poddy calf surrounded the home they called Belmont, which Grandma (Bridget) Charles had bought when her husband Richard was still working the orchards. Their son Phillip, better known as Dick, and his wife Stella continued on the orchard and raised two sons, Fred and Keith, and three daughters, Pat, Jan and Helen.

The tomboy of the family, Jan would go with her father to help round up or yard their small mob of Merino sheep. Dick was a punter as well as an orchardist, and when he left for the races on a Saturday the kids would slip into the packing shed and bounce on the spring-loaded platform that stopped apples from bruising as they tumbled off a conveyor belt.

“We would go swimming in the dam,” Jan said. ”He [Dick] wouldn’t let us in there because it would stir all the mud up for the stock. We’d come home, we’d have leeches hanging off us.”

When Dick was around, the children worked hard, as all kids did back then. They gathered up the near-ripe ‘’wind falls’’ that were blown from the trees.

“You would pick them up, and anything rotten you would put in another bucket, it was hard work,” Jan said.

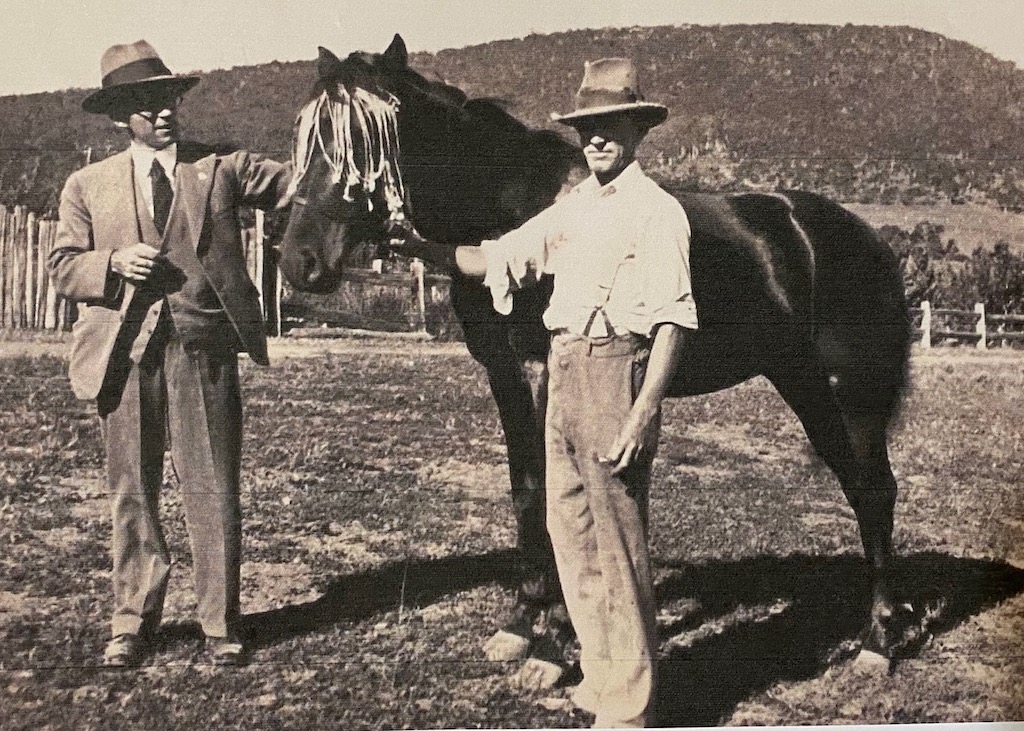

Ken Brewer and Dick Charles on the Charles property in 1933. The edge of the orchard can be seen beyond the timber fence on the right. Photo: Supplied by Heather West.

“The rows would be as long as this [house] block and there would be four rows and you would have to go around every tree.

“I would have been about 10 or 11, and carried the rotten fruit not good enough to sell and tip it over the fence for the sheep.”

But there were rewards too.

“I used to eat about a dozen apples a day,” Jan said. “I have never had a decent apple since [the orchard days].”

Most of the fruit was sent by train to the Sydney markets. Some of it was taken to Darcy Wheeldon’s fruit shop in the main street and customers also called to buy from the packing sheds during the picking season.

Peaches ripened after Christmas.

“They had these big yellow ones like that,” Jan said, stretching her fingers out to shape a lawn bowl. “Oh, beautiful peaches, I wish they were still up there.”

Having joined the workforce, her older brother Fred was riding a conveyor belt at South Portland mine at Marulan one day, as workmen did against company policy, when he slipped, crushing both his legs. One was amputated, leaving a short stump above the knee, the other was pinned.

As upsetting as it was for Jan, she nevertheless made the most of his 18 months in hospital. As a favour, she would kick-start his Triumph Tiger 100 motorbike in the shed and, when Dick was at the races, would ride the heavy bike into a paddock even though she could barely balance it.

When Jan married Jimmy Collins, they lived in an enclosed section of Belmont’s verandah for 12 months before moving into a brick cottage, which Dick bought them, over the hill next to East Goulburn Primary School.

Jan Collins says her 43 years cleaning at East Goulburn Primary School were made special by the teaching staff, who included her in their enduring friendships. Photo: John Thistleton.

Now deceased, Jimmy left Jan and their three little daughters early in the marriage. She has lived in the cottage ever since and for 43 years was a cleaner at the school, rising at 5:30 am to be at work an hour later.

She is the only surviving member of Dick and Stella’s family. Her two sisters died of cancer and she suspects their deaths were related to the toxic mercury, arsenic and lead-based sprays applied to their orchards. She’s a survivor.

“Probably because I ate all those apples,” the 85-year-old grandmother says.