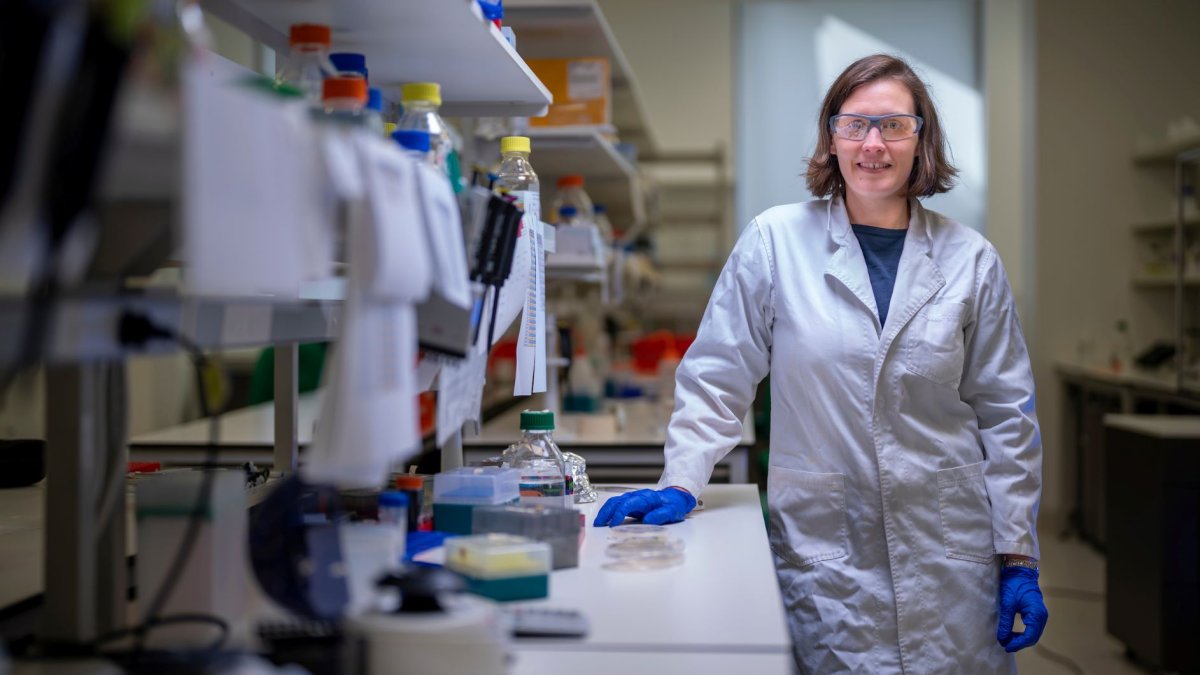

ANU Associate Professor Caitlin Byrt is one of the project’s advisers. Photo: ANU.

A world-first project to see whether plants can grow on the moon is set for take-off. Literally.

In 2022, the Australian National University (ANU) agreed to lend its expertise in plant biology to an ambitious mission led by Australian space start-up Lunaria One to grow plants on the moon.

And next year, it’s happening.

Plants and seeds ensconced in a carefully engineered capsule will make the 380,000-kilometre trip from Earth to the moon aboard an ”Intuitive Machines” lunar lander on a date to be confirmed in 2025.

The mission, dubbed the Australian Lunar Experiment Promoting Horticulture (ALEPH), was described as an early step towards establishing human life on the moon, and was awarded $3.6 million by the Australian Space Agency.

“The researchers hope the lessons learnt from this mission will help unlock new methods to boost sustainable food production on Earth and bolster food security in the face of climate-driven weather disasters,” the ANU said in 2022.

Back on Earth, in Canberra, Dr Caitlin Byrt, a bioengineering professor and plant scientist at the ANU, will be watching with bated breath.

“We’ve designed something that will work for what we understand is going to happen, but if one of the parameters is out, it might go bad and the material might perish,” she says.

“But we’re going to give it our best shot.”

Prime plant-growing territory. Photo: Andreas, Pixabay.

In addition to the ANU, the project involves the Queensland University of Technology (QUT), RMIT University, and the Ben Gurion University in Israel, as well as industry bodies.

Dr Byrt was chosen because of previous talks she’d given at the Australian Academy of Science in Canberra on “keeping plants and astronauts hydrated in space”.

“Most of my career has been related to crop productivity, so how we engineer crops to tolerate environmental extremes like drought and salinity and things like that,” she says.

She says growing plants in such conditions is technically not new.

“Plants have actually been grown in space for about 42 years, not on the moon, but on space stations,” she says.

“The first plant was one called ‘thale cress’, which is kind of like the lab rat of plants. So 42 years ago, people managed to grow one in a space station, and it flowered and produced seed, and since then, more than 40 different plant species have been grown in space. So that’s encouraging.”

The ones they settled on for the moon are “resurrection” plants, a hardy variety known for their ability to survive in desert-type environments, which can reach extremes in heat as well as cold.

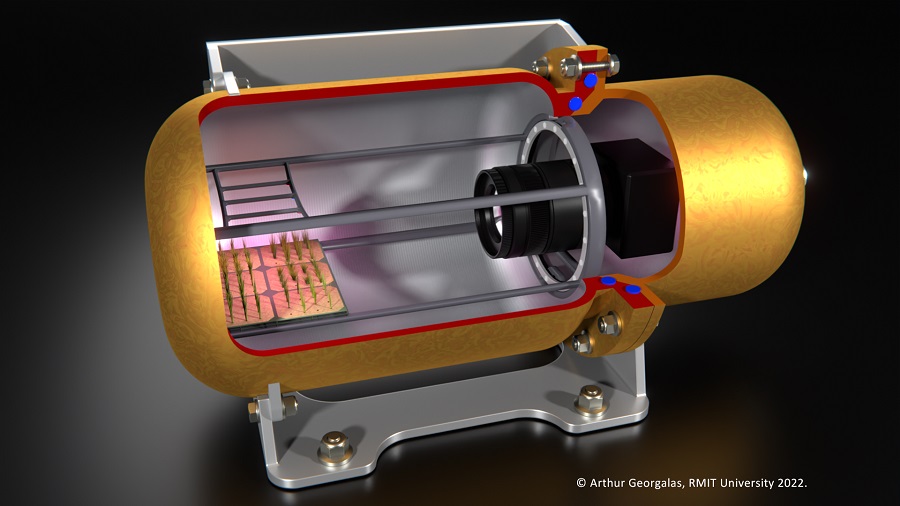

They’ll be transported in a specially designed chamber, completely sealed and with its own built-in camera, sensors, and hydration system, no mean engineering feat in itself.

An artistic rendering of the capsule that will house the seedlings. Photo: Arthur Georgalas, RMIT University.

Dr Byrt says the time when the plants are most at risk is actually on take-off.

“The vibrations are like aeroplane turbulence, but to the absolute maximum, so a lot of the engineering challenges relate to preparing the package to withstand that,” she says.

After landing on the lunar surface, the plants’ growth and general health will be monitored for 72 hours and data and images beamed back to Earth.

What researchers want to see in that time is photosynthesis.

“What we want is photosynthesis to happen on the surface of the moon in the terrarium, and to achieve that is going to be super difficult,” Dr Byrt says.

“Photosynthesis is a metabolic process, so your organism needs to be alive to do it. But this will be a massive step if it can be done.”

Citizen scientists and schoolchildren worldwide will also be invited to use the data to conduct their own experiments to identify which plant varieties have the best chance of growing on the moon, via the website www.plantsonthemoon.au.

Original Article published by James Coleman on Riotact.