Mary and Shlomi Bonet at the charmingly restored ‘Sweetwood Lea Inn’ at Breadalbane. Photo: Supplied.

When an old inn revealed its history to owners Shlomi and Mary Bonet, it prompted an almost two-decade-long love affair of restoring it to its former condition.

‘Sweetwood Lea Inn’ at historic Breadalbane, in the NSW Southern Tablelands, is a piece of colonial architecture built in the 1850s. Located on what was once the only route between Sydney and Melbourne – the two cities of colonial Australia – it is easy to imagine everybody who was anybody having either stayed at the inn or passed by it.

Between 1858 and 1878 it was a hotel, coach house and post office, and was known as Breadalbane Inn, Lodge’s Inn and Breadalbane Hotel. From 1878, the inn became a family home to John Hannan, and until 2002, it had been succeeded by his descendants.

By then it had fallen into disrepair and was empty, neglected and abandoned. It was nothing more than a shell keeping out the rain.

On a Sunday drive, Shlomi and Mary happened upon an open house held by a real estate agent.

“It was beautiful, it was affordable and it inspired us,” says Shlomi.

Among the rubble, the building echoed its colonialism in pressed tin-coated steel ceilings, Australian red cedar joinery, tall ceilings and open-hearth fireplaces.

“People make emotional decisions when they buy something like this,” says Shlomi.

“It is very much what I did all those years ago. It wasn’t a rational decision, it was an emotional decision because rationally you would walk away.

“It’s such a special thing to buy something that’s irreplaceable.”

Shlomi, an environmental scientist, was equipped with enthusiasm, but admittedly was inexperienced in building and renovation.

“I didn’t know what I was getting myself into, he says. “I think if I knew, I probably wouldn’t have done it.”

After many countless hours, the 170-year-old hotel has mostly been restored charmingly as Shlomi and Mary’s family home.

From the roadside, its iconic corrugated iron roof and verandah can be viewed. Inside, the layout features a single, long hallway running the length of the house to the country kitchen, and on either side of the hallway, doors are framed in Australian red cedar.

“They were practical buildings, utilitarian buildings,” says Shlomi. “They weren’t designed like we design houses today for luxury and comfort.”

While the house has been turned new again, it remains classically colonial with antique furniture, traditional stonework and tin-pressed ceilings in many of the rooms.

The gentleman’s room has been converted to the master bedroom. It was there, underneath the floorboards, where Shlomi found 21 colonial coins. He also found belt buckles, medallions, buttons, medals from World War I, religious medallions, jewellery, and copper brooches with enamel.

Many belt buckles are decorated with images of cricketers with bats and balls.

“They’re beautiful and they’re personal,” says Shlomi.

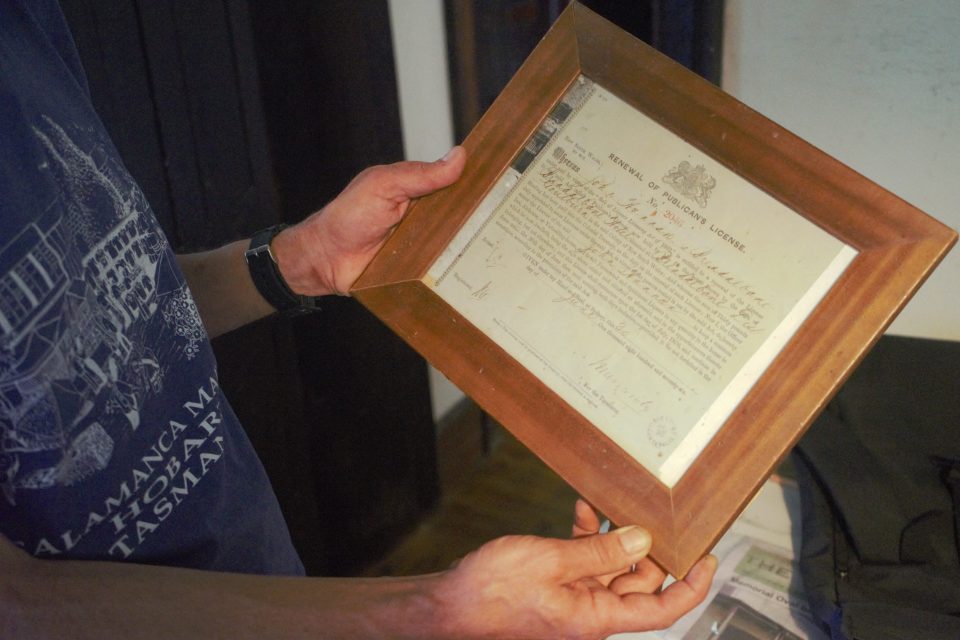

An interesting item was a children’s belt buckle with an inscription of the Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne. Some items can be dated to the 1850 and 1860s. Other pieces of interest were a publican licence to sell liquor entitled to Hannan from 1876; bottles; paper cartridges from a shotgun; lead bullets from a muzzle-loading rifle; and a metal gunpowder flask.

Shlomi also unearthed a sandstone headstone for James Thomas McCabe, born 11 June, 1869, which was buried in landfill. He has since corrected the registry for McCabe’s burial place at St Brigid’s Catholic Church and Cemetery, which is 300 metres from the inn.

“It’s not something you expect to find in the ground,” says Shlomi. “I first thought there was a grave.”

The Bonets’ theory that 19-year-old McCabe died by suicide and the headstone was vandalised after his burial in a Catholic cemetery is supported by academics. The death certificate showed the cause of death as peritonitis.

If the walls could talk they would also tell of bushrangers, including Frank Gardiner, Ben Hall, John Dunn, Johnny Gilbert and the Clarke Brothers who either robbed or sought shelter at ‘Sweetwood Lea Inn’ during the 1860s.

After the railway was built between Sydney and Melbourne, publican John Hannan held the inn as a family home, and following World War I it was used briefly as for the rehabilitation of returned soldiers.