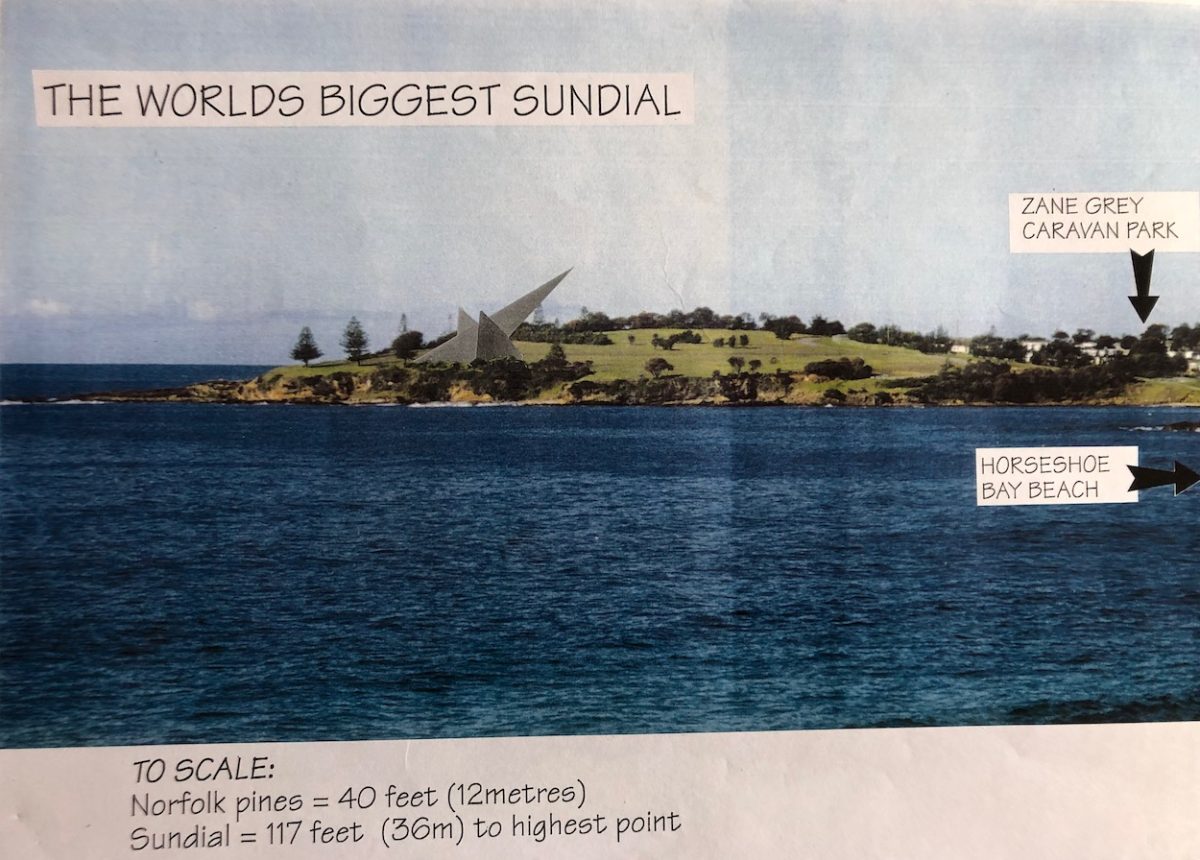

A scale model showing the sundial superimposed on the headland. Photo: Supplied.

There was great excitement among Bermagui businesses in the mid-1990s – the town had been chosen as the site for the world’s largest sundial. Funding had been easily secured and it had the support of Bega Valley Shire Council.

Timber milling had stopped several years before and there were not enough visitors coming to Bermagui to support its businesses. The sundial was the perfect solution. The world’s then-largest sundial in Jaipur, India was a huge tourist attraction.

Chris Franks was a member of the Bermagui and District Business and Tourism Association (BDBTA) at the time and was closely involved.

To mark its centenary in 1995 the British Astronomical Association NSW Chapter (BAA) wanted to build the world’s largest sundial. It had identified three potential sites on the 150th meridian: Bermagui, Lithgow and Marulan.

Council and a forerunner of Sapphire Coast Destination Marketing told BDBTA about the opportunity. The BAA would design it to ensure it worked accurately and BDBTA had to fund it. The cost in 1993 was $200,000.

“We put in a beauty of an expression of interest,” Mr Franks said. “We got it and then we had to meet everybody.”

BDBTA approached Bega Engineering who jumped at the opportunity to build it.

“Support for it came from every direction almost,” Mr Franks said. “It got good media coverage, and we covered the funding within a week of announcing it.”

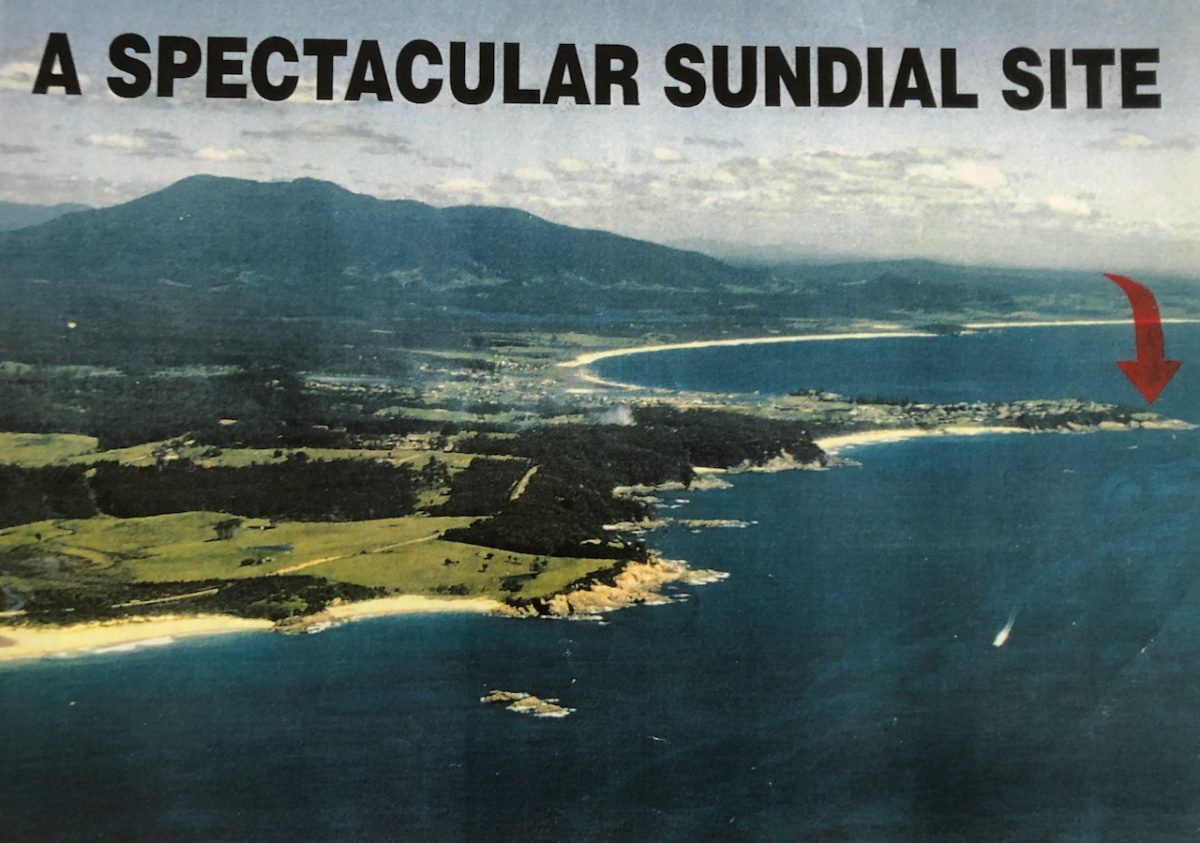

The sundial was to be built on Dickinson Point, some distance away from the caravan park and pub. Photo: Supplied.

Council was supportive, providing BDBTA went through the process which included preferably the full support of the district and the State Government. The State Government said it was on board if BDBTA got the district’s support.

The sundial was to be built on Dickinson Point with a 64-metre long gnomon and 36 metres at the highest point. It was to be landscaped into the surroundings and have a room at the base to sell souvenirs. It would have a strong educational component so school groups could learn about the sundial and the world’s oldest form of record keeping. It would also house equipment for improved communication with commercial fishers at sea.

At considerable expense, BDBTA had a model built showing the sundial superimposed on the headland to show its scale and position. There were pictures of it in shop windows.

Bermagui resident Judi Hearn recalled being approached by someone from out of town. “She had read about it and wanted to see it, thinking it had already been built, but locals were very much against it,” she said.

Meanwhile there were internal ructions at BAA. One outcome of the infighting was it withdrew its support for the sundial and would not provide the necessary engineering plans.

BDBTA learnt that on the morning of a public meeting it had organised to formally present the sundial proposal to the town.

“We went to the meeting knowing we had sunk our boat, but we wanted to keep the concept alive,” Mr Franks said.

“Then word got out that the association had pulled the plug and the meeting deteriorated. We stood our ground, lost a little blood, and watched them ride off into the sunset.”

Chris Franks, president of the Montreal Goldfield Management Committee, was one of the main drivers of having the sundial in Bermagui. Photo: Marion Williams.

Without the district’s support, the sundial also lost the blessing of the council and State Government.

“So, we said we would put it to bed. The locals said don’t put it to bed, put it in the fire,” Mr Franks said. “But we kept it to bring it out one day.”

BDBTA still had to contend with the reality that it needed something to bring visitors to the town.

“It was a constant challenge to appeal to the touring public to come into Bermagui,” Mr Franks said. “The business sector needs a certain volume of traffic, and we were falling short of it.”

So, after the sundial had fallen through, businessman John Neilson suggested doing something with the almost forgotten goldfield north of the town.

“We recognised the need went on and confronted the fact that within Bermagui’s boundaries it had been home to the only goldfield that had started a gold rush before the town really existed.

“We went on to investigate this goldfield and here we had this home-grown attraction that deserved our full attention,” he said. “We wanted something to appeal to the general public so investigated if it had a story which of course it did.”

Montreal Goldfield opened to the public in April 2005. It is listed on the National Heritage Register. Without the goldfield, Bermagui may have become an international tourist destination for having the world’s largest sundial.