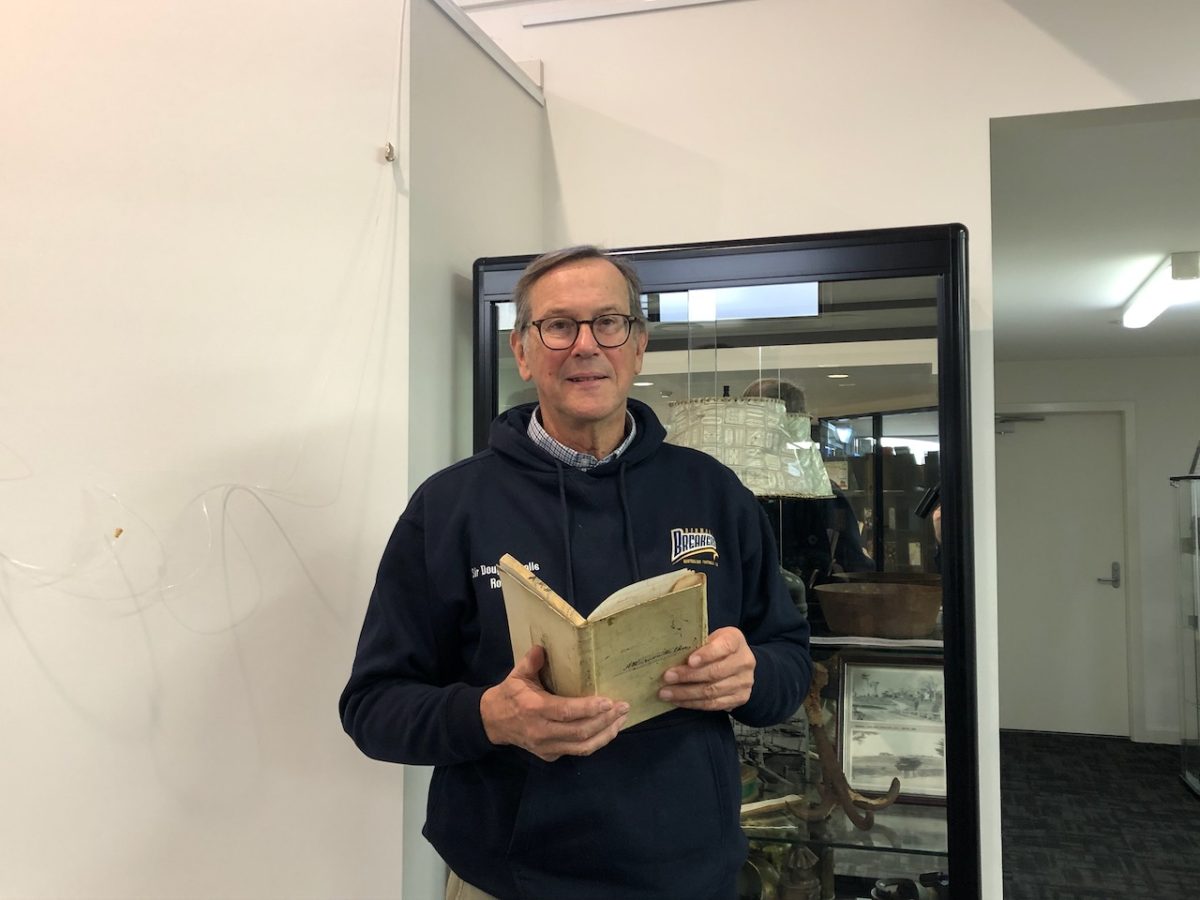

Bermagui resident Stephen Mills’ latest book is partly based on his uncle’s diary while at Duntroon. Photo: Marion Williams.

Very few Australians alive today can say their father or uncle fought at Gallipoli. Bermagui resident Stephen Mills can. Author of a Bob Hawke biography, he is now writing a book about his uncle, Arthur Curwen-Walker.

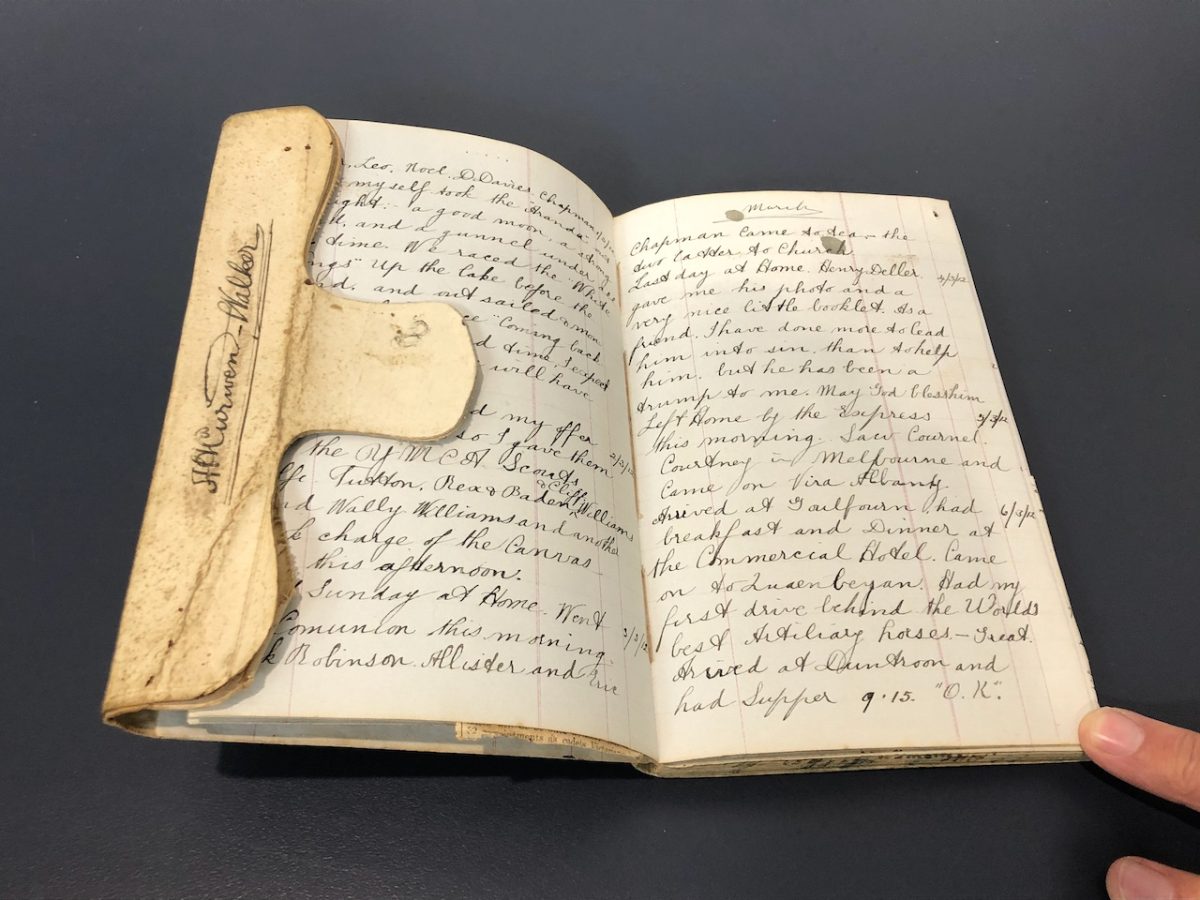

One of his resources is the diary that Arthur kept while training at the Royal Military College in Duntroon. He was in the second intake of cadets in the yet-to-be-named national capital.

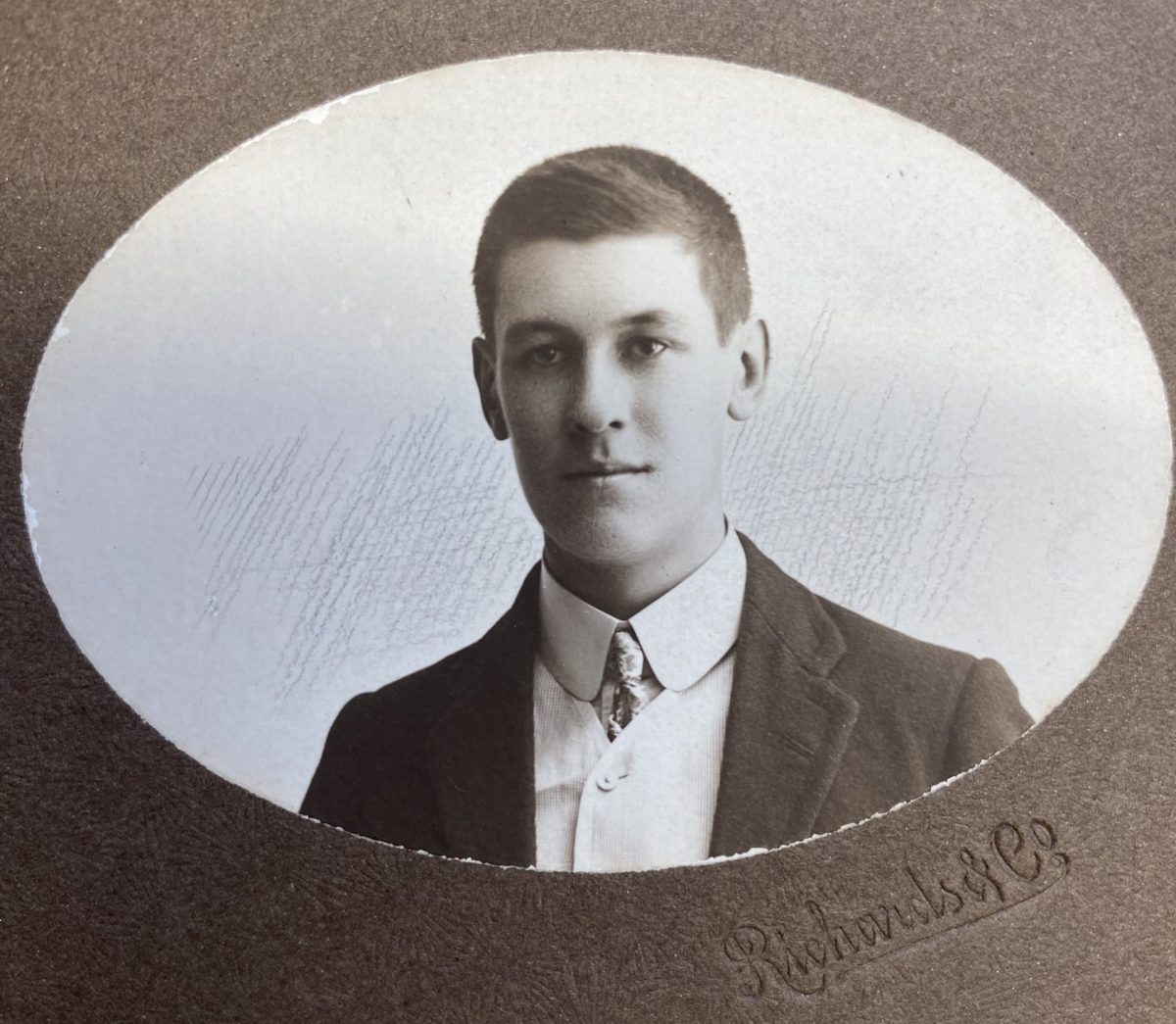

Arthur was born in November 1894. He loved the outdoors and had no interest in following his lawyer father’s footsteps. A member of the Boy Scouts, Arthur enjoyed hiking, camping and shooting.

“There must have been an allure about Duntroon. It was brand new, and you had competitive exams to enter it,” Mr Mills says. Like West Point, entry was by merit unlike England’s Sandhurst.

An early entry in Arthur’s diary is ‘Red Letter Day’, the 17-year-old’s jubilant exclamation that he had been accepted into Duntroon. He arrived at Duntroon in March 1912 and described his first day as “absolutely spiffing”.

“It was in Canberra but there wasn’t much to Canberra at that point,” Mr Mills says. The cadets called Duntroon the “clink”, a cross between a monastery and a penitentiary. The winters were cold, causing the water boiler to explode, and the summers so hot they slept out on the veranda. Sometimes they escaped to camp at Cotter Reserve where they smoked pipes, had barbecues and slept in.

Arthur enjoyed woodwork, carved boomerangs and made canoes from blackwood and with canvas that he purchased in Queanbeyan. He paddled them on Molonglo Creek.

He was a member of the Christian Club and an early dabbler in photography. “Amazingly, some photos have survived,” Mr Mills says. “They are very moody images of dappled sunlight and leaves on the water so that is pretty interesting for a kid who is still a teenager.” Towards the end of the journal Arthur started writing poetry.

An old family photograph of Arthur Curwen-Walker. Photo: Supplied.

Arthur’s longest diary entry is 12 March 1913, the day the Governor-General’s wife, Lady Denham, announced the name of the new capital. Arthur was among the Duntroon cadets who formed the guard of honour and misheard the new capital’s name as “Camberra”.

For Arthur, the ceremony was far from the day’s most important event. One of the survivors of Scott’s ill-fated Antarctic expedition, second-in-command Lieutenant Evans, gave a presentation to the cadets at Duntroon.

Arthur was inspired and enthralled. “Lecture given by Commander Evans of the Scott Antarctic Expedition. Scott said when canvassing for funds, “Even if we don’t achieve anything you will have no cause to be ashamed of us”.

“Scott’s code was: others first, self not at all; perfect good fellowship; keep your tongue between your lips; do not blow (i.e. boast).

“Two men dragged Evans against his orders 40 miles in four days working 15 hours per day and so saved his life, which he would have given for them.

“He and the heroes of that expedition (every man of them) have set a standard for us to follow. May God help us to do so and England ‘will have no cause to be ashamed of us.'”

The diary that Arthur Curwen-Walker kept while training at the Royal Military College in Duntroon. Photo: Marion Williams.

Such sentiments undoubtedly drove enthusiasm at Duntroon for the decision, when war was declared in 1914, to allow Duntroon’s first two classes to graduate early and enlist in the Australian Imperial Force.

Arthur was appointed a lieutenant in the 14th Battalion and embarked in December for Egypt and then Gallipoli.

“When he went to Gallipoli, the 14th Battalion formed the reserve and Arthur went ashore on 26 April under Brigade Commander John Monash,” Mr Mills says.

“The next day they climbed the gully under shrapnel fire and made their way to Courtney’s Post on the ridge. Australian trenches were just metres from Turkish trenches and the fighting never let up.

“On 2 May he was shot in the stomach and mortally wounded, carried downhill on a greatcoat and evacuated on a hospital ship. He died on board on the way to Egypt and was buried at sea.”

Arthur’s family was notified by telegram. He was the eldest of four. “My mother wasn’t yet born,” Mr Mills says. “He was killed in 1915 and my mother was born in 1917.”

Arthur’s death devastated the family. “My mother was always very aware of the brother who was no longer around,” Mr Mills says. “I think she was raised in his shadow and picked up the grief of her parents and family.”

Mr Mills has always known about Arthur’s diary which his mother passed down to him. “To hold it as a kid was incredibly special.”

He went to the Anzac dawn service at Gallipoli this year to see where Arthur fought and died and to think more to help write the book.

“You can’t get over that sense of shock of all these 20-year-olds getting killed after their training and hard work.”