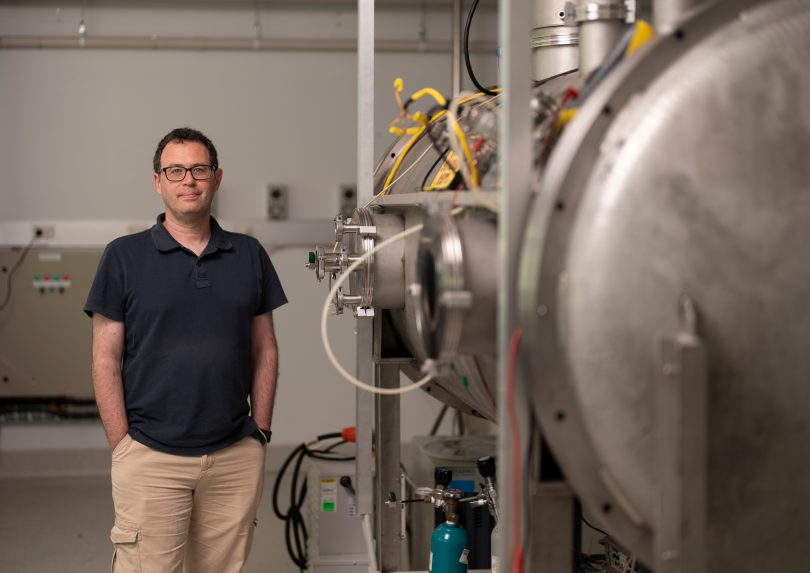

PhD candidate Dimitrios Tsifakis from the ANU Research School of Physics is undertaking research into using naphthalene as a ‘CubeSat cold gas thruster propellant’. Photo: Jamie Kidston, ANU.

The next time you’re at granny’s house, open her wardrobe and take a deep sniff. That’s rocket fuel you can smell.

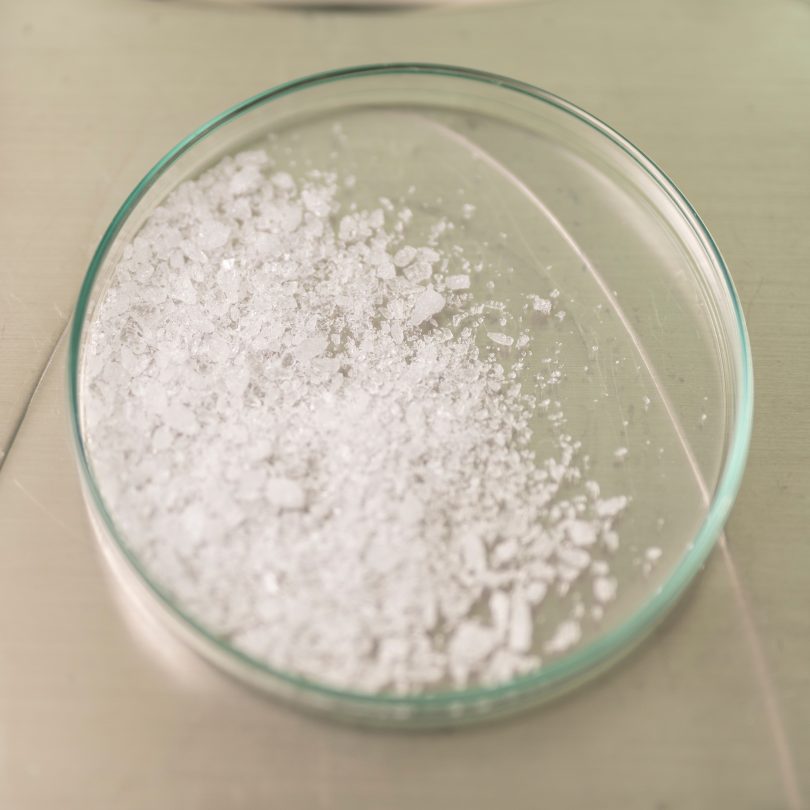

Naphthalene might be better known as ‘mothballs’, but the smelly and solid white substance is at the heart of a new rocket propulsion system designed and tested at the Australian National University (ANU).

ANU PhD scholar Dimitrios Tsifakis came up with the idea of using naphthalene for the CubeSat project and describes it as the perfect alternative to hot and charged gas plasma.

“It is cheap, non-corrosive and easily available – you can get mothballs in the supermarket,” he says.

Not only is it cheap and easy to source, but when heated, naphthalene converts from a solid to a gas, eliminating the danger of having liquid sloshing about in the rocket’s thruster.

“Everyone knows that old smell in granny’s wardrobe – now it is the newest thing in space technology,” says Dimitrios.

ANU scientists have designed the innovative thruster, with its very familiar odour, in only six months from design to delivery. Primary testing was conducted on campus in Acton.

A dish of naphthalene used in the testing of a rocket for the Bogong satellite. Photo: Jamie Kidston, ANU.

Powered by the new technology, the aptly named Bogong satellite will launch into space in mid-2022 among half-a-dozen other small satellites that Australian space services company Skykraft will use for tracking and communication with aircraft, facilitated by Canberra-based space company Boswell Technologies.

Dimitrios says rocket scientists have turned to mothballs in the past, but thanks to these two Canberra companies, ANU is the first to produce a fully functioning thruster in their lab.

The Bogong thruster will warm up the substance to about 70 degrees Celsius, or when it turns into gas, before heating it even further during its exit from the thruster nozzle.

Exposure to very large amounts of naphthalene can cause damage to blood cells in humans and animals, but Dimitrios says emissions from the thruster are no cause for concern.

“The naphthalene thruster will only be operated when the satellite is in space so there is absolutely no risk of it causing any harm,” he says. “It can be considered a ‘green propellant’ as it is much less dangerous than other propellants used.”

Dimitrios says scientists have detected naphthalene in space so “it’s already up there”.

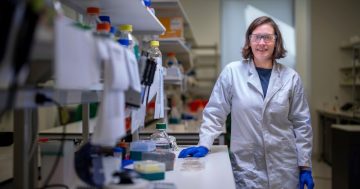

Engineers preparing the naphthalene-powered Skykraft satellite at ANU. Photo: Jamie Kidston, ANU.

Project leader Professor Rod Boswell, from Boswell Technologies, describes the Bogong and its family of mothball-powered satellites as the “first step in making global aviation safer in a cost-effective way”.

The team says the new thruster design could extend satellite life by up to 20 per cent – equivalent to an extra year of service – because the simple design uses more propellant than a conventional plasma thruster, but houses very few complicated electronics. This means its space can be used to house more naphthalene.

Professor Christine Charles, head of the ANU Space Plasma, Power and Propulsion laboratory, led the rocket trials by heating prototypes in a space-simulated vacuum chamber called ‘WOMBAT’.

“There are very few places in the world that can test space conditions, conduct lab work and work closely with industry,” she says.

“We refined it every day with our thrust balance, and now Bogong is ready to launch. Launching mothballs in space could make the skies safer.”

Original Article published by James Coleman on Riotact.