Tumut-born Canberra-based artist Aidan Hartshorn with his mentor for the Country Road + NGV First Nations Commissions program, James Tylor. Photo: Jacinta Keefe.

A Tumut-born artist whose ancestral homelands are the high country and Riverina regions of Australia is punching right through the noise of everyday life in Melbourne’s CBD right now.

Federation Square is where you’ll get first glimpse of the work of Canberra-based artist, Walgalu and Wiradjuri man Aidan Hartshorn.

There, the big screens are aglow with the latest offering at the nearby National Gallery of Victoria’s spectacular Ian Potter Centre, which is the result of a year-long national mentorship program and exhibition series under the banner Country Road + NGV First Nations Commissions.

The new national biennial initiative paired eight emerging Australian First Nations artists from every state and territory with esteemed industry mentors to produce their most ambitious work to date, which, in its first iteration, responds to the theme ‘My Country’.

Reflecting the scope of the initiative, outcomes in the current exhibition range across a diversity of media, including textiles, customary cultural objects and large-scale paintings to installations that engage glass making and new modes of fabrication.

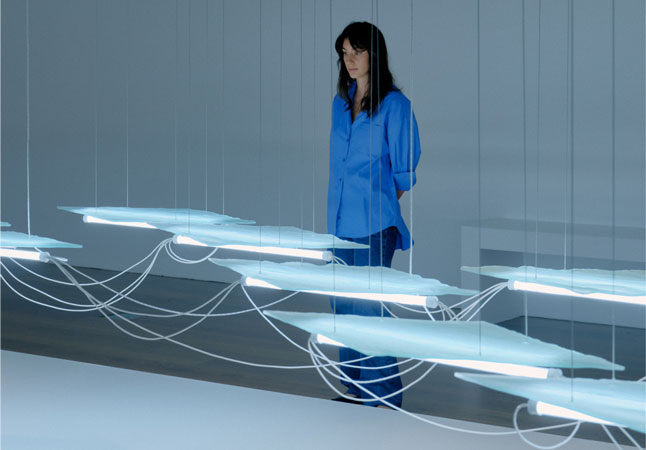

Aidan Hartshorn had previously never worked with glass, but seeking to push himself and his practice, and in the spirit of the program, he chose the medium to create an installation, titled These Violent Delights.

By suspending 16 diamond shapes – representative of traditional Wiradjuri bark shields – in the formation of the now-hidden Tumut River and illuminating them with blades of white light, he has produced a work that gestures to the impact of the 16-dam Snowy Hydro Scheme on Walgalu Country and cultural sites.

Aidan says Walgalu or Wolgal Country is a somewhat forgotten part of the high country’s First Nations and colonial histories, but the installation, he hopes brings this part of his heritage visibility and voice.

Raised in Tumut, with the headwaters of the Murrumbidgee River and Tumut at their heart, he says his family grew up surrounded by their culture but it was one they had increasingly limited access to with the evolution of the Snowy Hydro Scheme in the 1960s.

As the spiritually significant water was harnessed, so too were their traditional gathering spaces and practices, but the stories remained, passed onto Aidan largely through his father, who worked as a heritage officer for the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

Installation view of Aidan Hartshorn’s work These violent delights on display in My Country: Country Road + NGV First Nations Commissions at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne. Photo: Tom Ross.

“Bringing visibility to the ancestor’s voice and to other ancestors and spirits is an important part of my practice,” he said, “and I’m interested in looking at ways how we, as Walgalu people living and practising today, can create new forms of practice and culture.”

He credits his mentor, multidisciplinary contemporary visual artist James Tylor, in helping to manifest those ideas into form, but also forcing him to consider the question of what it means to be a Walgalu person practising in 2024.

Theirs is a friendship forged in 2017, at a time when Aidan was at the point of bringing his cultural storytelling to the forefront of his work.

“I think back on my 29 years and there was never a moment where I wasn’t going to be a maker, or I guess an artist,” he said. “It was in my blood.”

His grandmother Vicki Hartshorn taught him how to draw, a passion that evolved in high school to his first taste of artistic success as one of a small number of HSC students selected to show artworks in 2013’s Art Gallery of NSW ARTEXPRESS exhibition.

“Art has always been my drive and coming from a small town, I didn’t know what that would look like as a career, but I’ve been lucky,” he said.

Upon leaving school Aidan took time away from the fine arts, developing more skills working with sculptural mediums until 2016 when he enrolled in the Australian National University’s School of Art and Design.

Joining the sculpture department, Aidan found a passion for constructing objects tied to his dual cultural background and through his practice explored the destructiveness of colonial processes and the connections to Country he and his people have with the ever-changing landscape.

In 2019 he completed his tertiary education – the first in his family to do so – attaining a Bachelor of Visual Arts majoring in sculpture.

After joining the Wesfarmers Leadership Program he would later become part of the First Nations team at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) where, for two and half years, he worked on the 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial (NIAT) with curators Hetti Perkins and Kelli Cole.

He describes the process of creating These Violent Delights as amazing.

“I keep saying this, but as an emerging artist, the amount of support we were given to do the work, meant we didn’t have to think within a boundary — I didn’t have to limit myself and we were given enough time and support to do something meaningful,” he said.

Something he appreciated in the works of his fellow exhibitors.

“Seeing other works in the exhibition made me realise that the narrative is not that different to others. We are all fighting for the same things,” he said, “which is to be seen and heard.”

The Country Road + NGV First Nations Commissions: My Country is on until 4 August at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Federation Square, Melbourne.