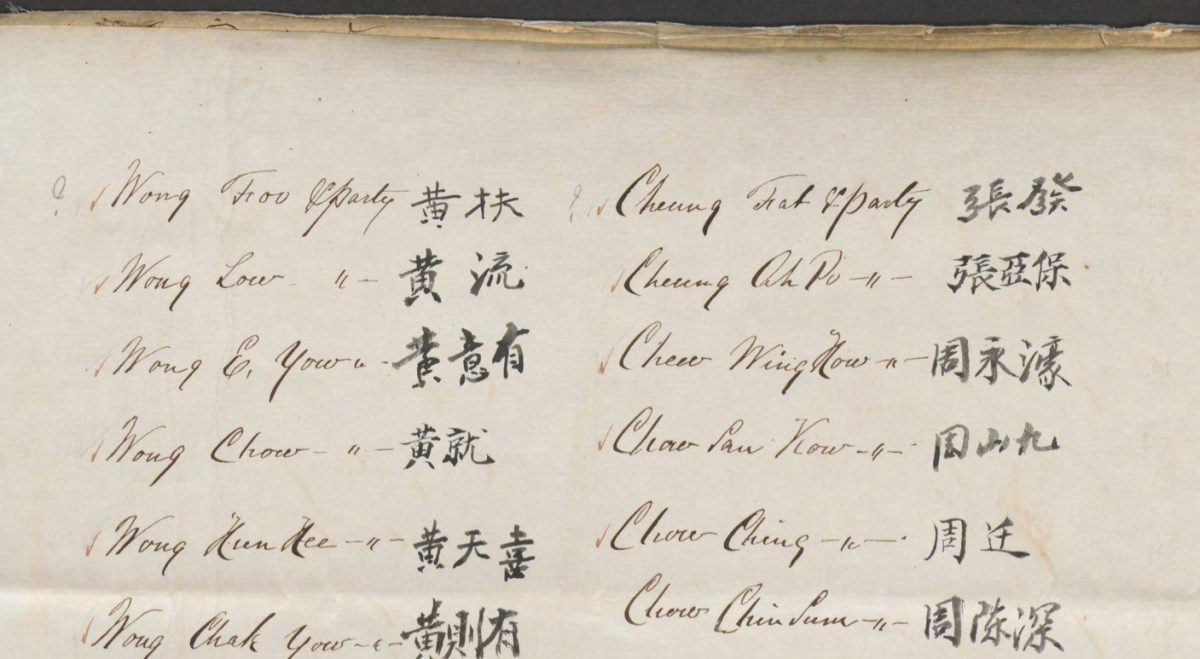

The names of 94 persons who were at Back Creek at the time of the major riot on 30 June 1861 are contained on one of the petitions. Photo: Museums of History New South Wales – State Archives Collection.

A collection of rare petitions from Chinese miners violently expelled from the Burrangong goldfields during the Lambing Flat riots has been made publicly accessible, offering fresh insights into a long-overlooked chapter of Australian history.

Containing vivid first-hand accounts of their experiences leading up to and following the series of skirmishes between November 1860 and July 1861, there are also hopes the digitisation and release of these historic documents which also contain lists of names, will help Chinese Australian family history researchers determine if their ancestors were present at Lambing Flat during that time.

As gold fever gripped the colony, the confrontations in and around what is now the Hilltops town of Young – where gold was first discovered on a sheep station in mid-1860 – were among the most violent anti-Chinese disturbances of Australia’s gold rush era.

Within months of that discovery tensions rose as swiftly as the population exploded as miners of every nationality flocked to the settlement to stake their claims.

Unlike their European counterparts, the Chinese miners often worked in cooperative groups, meticulously reworking abandoned claims and recovering gold from areas others had deemed exhausted.

Their success, coupled with existing racial hostility and lack of law enforcement, led to resentment among European diggers who would collectively drive the Chinese off their claims and into the surrounding bush, leaving many of them injured and destitute.

The violence would reach a peak on 30 June 1861, when thousands of European miners assembled and marched through the various settlements, storming the Chinese camps torching tents, looting possessions and brutally assaulting those who could not escape.

Although colonial authorities eventually responded by dispatching troops to restore order, few rioters faced consequences for their actions, instead, the riots contributed to the rise of restrictive anti-Chinese policies, which later culminated in the White Australia policy.

But two handwritten petitions, preserved in the Museums of History NSW State Archive Collection, document the desperate pleas for compensation from Chinese miners whose camps were ransacked and burned.

These documents have been made more accessible online thanks to the efforts of Our Chinese Past, a not-for-profit organisation of historians and genealogists dedicated to preserving and promoting Chinese Australian history.

Founded in 2020, the team focus on the digitisation and translation of heritage materials, historical records, and photographs, making them more widely available and better understood.

Since its inception, the organisation has collaborated with museums, historical societies, communities and heritage groups to raise awareness of this history through websites, apps, publications, signage and displays.

Their ongoing work has resulted in a series of projects that expand access to Chinese Australian heritage materials, ensuring that these important records are preserved and shared with a broader audience.

Scenes reminiscent of Lambing Flat’s riots are exampled in Might versus Right by S T Gill, c.1862-1863, J T Doyle’s sketches in Australia by John Thomas Doyle & Samuel Thomas Gill. Photo: State Library NSW.

The first of the Lambing Flat Chinese petitions, dated 12 March 1861, was handwritten in English by Su San Ling Doh, who had arrived in Lambing Flat on 22 December, 1860.

With a miner’s right from the Snowy River (Kiandra goldfield), Su San Ling Doh began mining on 25 January, 1861 but by the 27th, Europeans had demanded that the Chinese leave. Su requested time to remove his belongings, but was denied. On the 27th, he and other Chinese miners were forced off the diggings. When he returned on the 28th, he found his tent burned and his £300 worth of belongings stolen by a group of Europeans.

In the petition he pointed out clearly that he had a licence to be on the field, and expected but did not receive the protection of the law.

Su San Ling Doh’s petition to the governor was presented to the NSW Legislative Assembly by Henry Parkes on 14 March 1861.

His petition, and the petitions of others would result in the appointment in May 1861 of Boorowa magistrate, William Campbell, as special commissioner to consider the compensation claims.

Despite requests that the commission be conducted in Bathurst or Sydney, claimants had to return to Lambing Flat to submit their claims in person.

But before the claimants could meet with Campbell, the largest of the Lambing Flat riots took place on 30 June 1861.

The NSW Government would eventually agree in 1862 to allocate £4240 in compensation, but bureaucratic delays, translation issues and miscommunication meant that many claimants never received their payments.

Despite these injustices, according to Our Chinese Past, the names of those affected were not lost to history thanks to the Museums of History New South Wales — State Archive Collection which granted permission for the petitions to be reproduced on its website.

Our Chinese Past hopes, by sharing the documents online, it might assist not only researchers and historians reconnect with this difficult but important part of Australia’s story but also allow descendants to establish if their ancestors were at Lambing Flat.

“The petitions provide a direct link to the voices of those who suffered at Lambing Flat,” said a spokesperson. “By making these records accessible, we hope to assist descendants in uncovering lost family connections and ensure this history is not forgotten.”

The digitised petitions and further details can be accessed through the Our Chinese Past website or its Facebook page.