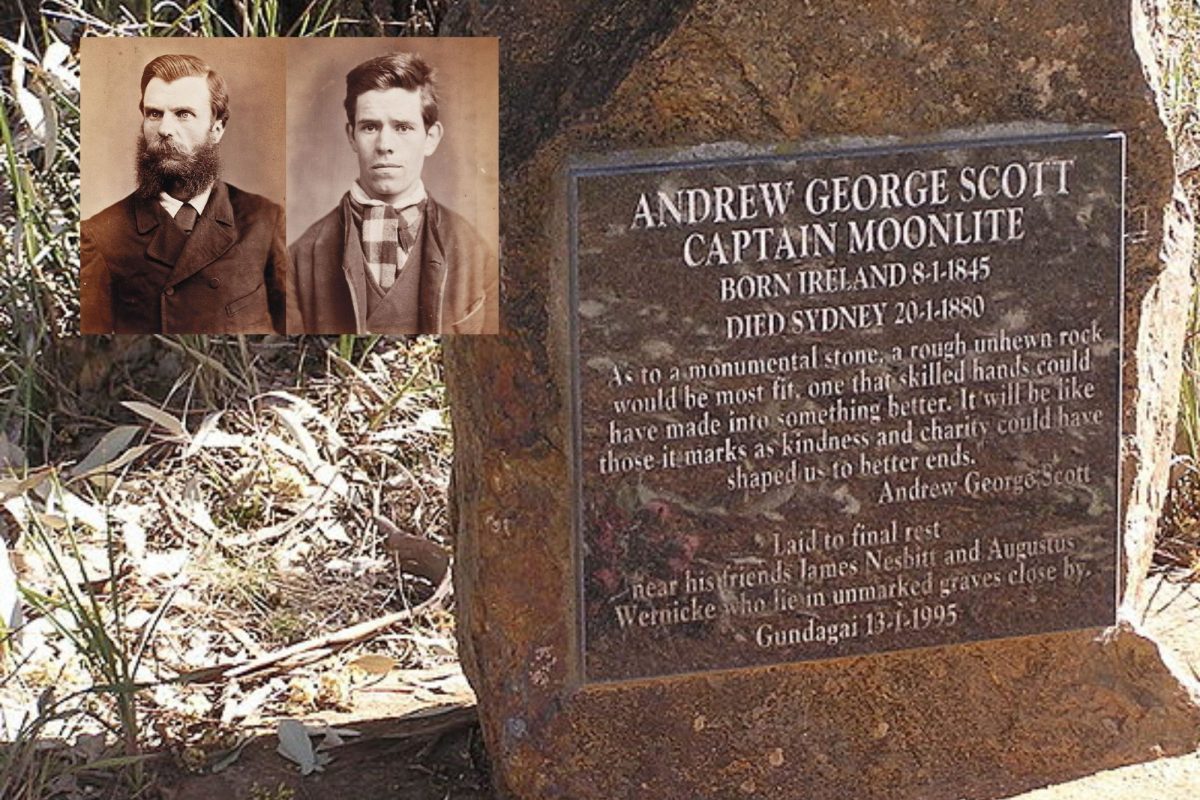

The final resting place of Captain Moonlite (inset left) and his companion James Nesbitt (inset right) at North Gundagai Cemetery has now been recognised as a site of historical significance. Image sources: Wikimedia.

For more than a century, the graves of bushranger Captain Moonlite and his devoted companion James Nesbitt lay in separate cemeteries, divided by history and the rigid moral codes of their time.

Now, their final resting place at Gundagai has been recognised as a site of historical significance, offering a rare and poignant insight into same-sex relationships in 19th-century Australia.

The graves, located in the historic North Gundagai Cemetery, were recently listed on the NSW State Heritage Register, testament to shifting perspectives on Australia’s past.

Far from the typical image of rough-and-tumble colonial criminals, the story of Captain Moonlite — born Andrew George Scott — and James Nesbitt challenges long-held narratives, casting their relationship in a new light.

Born in Ireland in 1845, Scott was an educated man who initially seemed destined for a conventional life.

But by 1869, he had turned to crime, robbing a bank in Victoria under the flimsy disguise of a mask and cloak before heading north over the border to NSW, where his fraudulent efforts earned him two concurrent prison sentences, totaling 30 months, of which he served just 15.

His Victorian robbery would eventually catch up with him, and as he served out a 10-year sentence in Pentridge Prison, he would cross paths with petty criminal Nesbitt, a meeting that would define the rest of his life.

Following their release, Scott and Nesbitt, along with a small band of followers, attempted to carve out a life in NSW.

But in 1879, an ill-fated siege at Wantabadgery Station near Gundagai led to a violent shootout.

Nesbitt was killed in the exchange, leaving Scott — cradling his dying companion — reportedly inconsolable.

Soon after, Scott was captured and sentenced to death.

Awaiting execution in Sydney’s Darlinghurst Gaol, he would pen more than 60 letters, many addressed to authorities and the press, attempting to explain his actions.

But his most heartfelt words were reserved for Nesbitt’s mother.

In one letter, he wrote:

“… his hopes were my hopes, his grave will be my resting place, and I trust I may be worthy to be with him where we shall all meet to part no more …”

Scott’s final wish — to be buried alongside Nesbitt — was denied when in January 1880, he was hanged and buried in Sydney’s Rookwood Cemetery, 300 kilometres from the man he had so deeply loved.

For over a century, their separation endured until the early 1990s, when Christine Ferguson and Sam Asimus from Gundagai, moved by Scott’s letters, launched a campaign to reunite the two men.

In January 1995, after 115 years apart, Scott’s remains were exhumed from Rookwood and reinterred near Nesbitt’s grave, beneath a eucalyptus tree in North Gundagai Cemetery.

Their story, once buried alongside them, has gradually emerged into public consciousness offering a rare window into same-sex relationships in an era when homosexuality was harshly suppressed by the state, challenging typical stereotypes of Australian bushrangers and providing one of the few publicly acknowledged same-sex relationships of the 19th century.

Walkley Award-winning writer Garry Linnell, author of Moonlite, underscored the cultural significance of this recognition.

“Colonial Australia was so starved of legendary figures that it seized on bushrangers as its first folk heroes — men who, despite their frequent boorishness and cruelty, defied authority and lived beyond society’s strict rules,” he said.

“Everyone thinks of Ned Kelly, but there’s no greater example of 19th-century outsiders than Captain Moonlite and his companion, James Nesbitt. Not only were they accidental bushrangers forced into crime by poverty and victimisation, their tale is also one of the greatest and most complex love stories in Australian history.

“They were not hardened criminals by choice but men pushed into crime by poverty and circumstance. At its heart, their story is one of the most profound and complex love stories in Australian history.”

Mr Linnell emphasised that the listing of their graves is more than a historical footnote.

“Adding Moonlite’s grave in Gundagai to the NSW State Heritage Register doesn’t just recognise the role he and Nesbitt played in shaping a young nation. It formally acknowledges a relationship that, for more than a century, was buried beneath speculation and silence.”

Cootamundra-Gundagai Regional Council Mayor Abb McAlister is delighted at the news.

“This is a town deeply steeped in history and folklore,” he said, “and Captain Moonlite’s name has rung through these hills since 1879.

“And how ironic is it that the community he and his gang terrorised all those years ago would be the very community who would fight to see his final wishes honoured all the while revealing a deeper, more touching story, that earns him a measure of admiration.”

NSW Heritage Minister Penny Sharpe echoed this sentiment: “Captain Moonlite and James Nesbitt were outcasts even among outcasts, who might have lived very different lives in more contemporary times.”

For Stephen Lawrence, Duty MLC for Cootamundra, the decision ensures their legacy will not be forgotten.

“The protections afforded to the gravesites in North Gundagai Cemetery ensure that this rare, one-of-a-kind site, and the life story it represents, are preserved,” he said.

What does it mean to be listed on the NSW State Heritage Register?

- It means the item is officially recognised as having high heritage significance

- It means the item is eligible for heritage conservation grants

- It means the item cannot be damaged, destroyed, altered, or moved without approval from the NSW Heritage Minister

- It means local councils must consider the effects of any proposed development in the area.