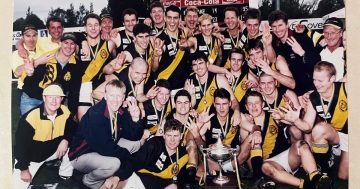

Whether it was a Test match in Sydney or a local derby at League Park in Goulburn, rugby league produced all the drama of a theatre production, according to Trevor Menzies, who had a starring role in the middle of the paddock. Photo: John Thistleton.

Northeast of Goulburn near Taralga, remote mountain ranges and the meandering Tarlo River are unlikely places for grazing livestock.

When pioneers from the 1920s, the Menzies family began running sheep on leases in this harsh country, heavy losses were constant.

Trevor Menzies, who grew up in this godforsaken countryside, likes to quote historian Lachlan Ross who once said, “Any man who runs sheep in the Cookbundoon must have a terrible set against himself.”

Yet generations of the Menzies grew to love the countryside. “We grew up with cats and dogs and pigs and pet lambs, milking cows and Mum (Jean) churning the milk to get the cream to make the butter,” he said.

“There is a spirituality about the bush, about the mountains; you feel it when you are there,” he said. “To see the fog come over the mountains of a morning, all you can see is a peak sticking out like an island, and star-lit nights they are something beholden to the soul.”

His forebears earned their pioneering reputation on horseback. Trevor earned his legendary status on rugby league fields.

After the 1974 Taralga Tigers beat Tarago to complete the second division season undefeated, having amassed 440 points while conceding only 64, a huge fight erupted in the beaten side’s hotel, The Loaded Dog.

As men with flailing fists tore into one another, someone found Trevor having a beer in another room with publican Ron Fielding. Once alerted to the fight, their desperate attempts to break it up were flattened too.

“Ron gave me a case of beer and said, ‘Get these bastards out of here because the cops are on their way,’” Trevor said.

Tarago’s former first graders from Goulburn had thought they could intimidate the Tigers, who were mostly shearers and farmhands with little playing experience.

But Trevor, the Tigers captain-coach who to this day jumps to his feet and talks passionately with his outstretched hands and blue eyes alight with excitement, had all the experience his side needed.

He had played for Oberon under captain-coach Tony Paskins, who created such a winning culture in the Group 10 club it won 10 grand finals out of 12 in the 1960s and 1970s and only lost the other two by a single point.

“He taught you what came before the game,” Trevor said. “His greatest thing was training and fitness.”

Leaving Oberon, Menzies took up as captain-coach of Merriwa, a wheat and sheep town on the edge of the Hunter district in Group 21.

“If you come and train with me – not play, train – I will pick you in my side and we will win,” he would say to his players, as Paskins had said to him. “But if you don’t come and train with me I won’t pick you in my side.”

Most players obliged. Some didn’t. “I got myself into trouble with certain blokes through the years,” he said, reflecting on his rigid rule. “You can’t do this Menzies”, they would say as they left in a huff.

A non-drinker in his early football days, he had followed Paskins’ advice when moulding his own teams as a coach, to have a drink and talk with his players after the games on Sundays.

“In that one night you will find out more about your players than you’ll find out through the week,” Paskins, who also coached Manly and Eastern Suburbs in Sydney, had told him.

As well as coaching the first grade Merriwa side, he kicked off a junior side, defying the club’s committee, who told him they did not have enough players. In one game Singleton beat them 64-nil. But Trevor persisted and gradually built up their numbers, skills and love of football.

He took the first graders from last to premiers for two seasons, represented Northern Division that beat France and was Group 21’s best-and-fairest player. He was at the club long enough to see some of the juniors join first grade.

A halfback who can still recall his coach from the Goulburn St Patrick’s Primary School’s 5-stone-7 side, Brother ‘Chippa’ Molloy, Trevor enjoyed the camaraderie of playing with and against tough men.

He coached Goulburn United in Group 8, ended his coaching career at Gunning in second division and today draws similarities between what the game taught him, and making the most of the rugged country around Tarlo River.

“It was like playing footy; it wasn’t about making money because there was no money to be made there,” he said.