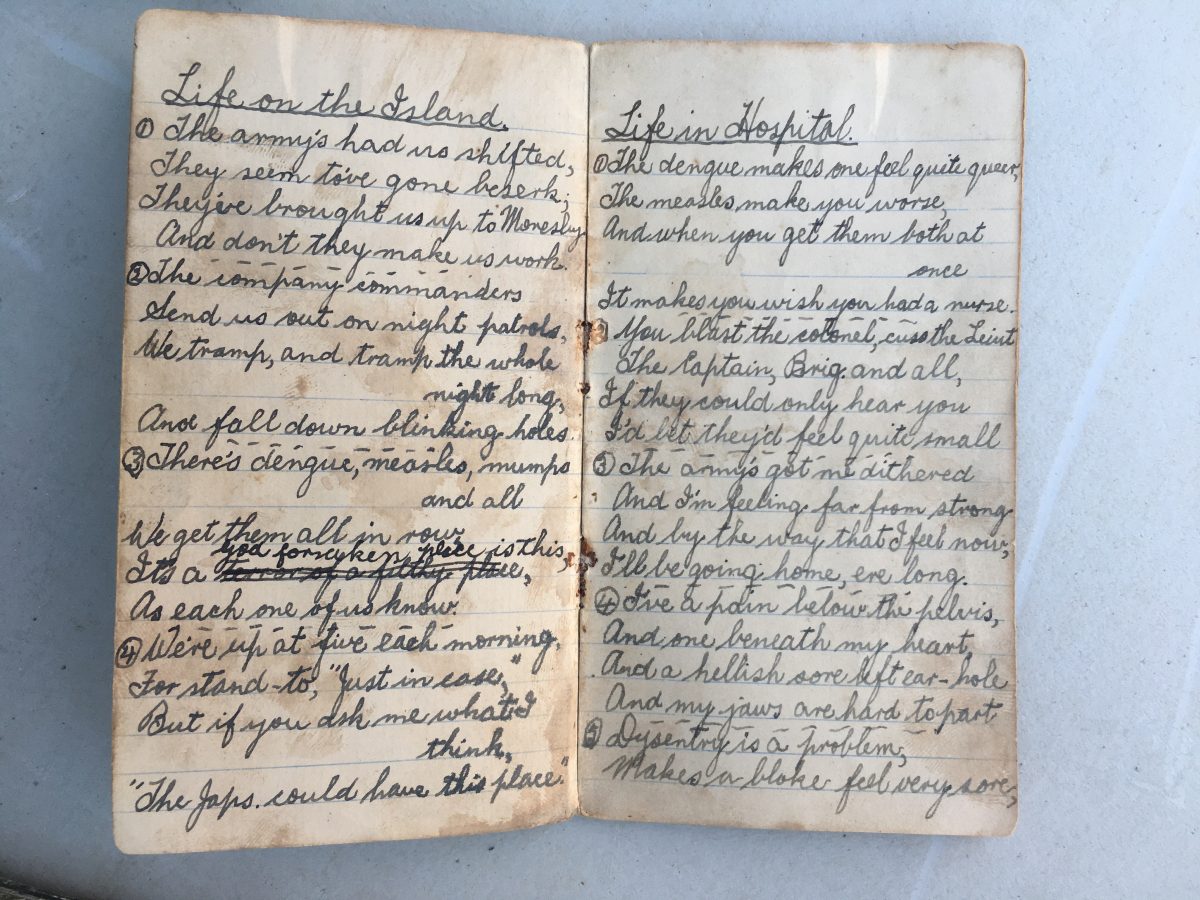

Two pages of poetry from Reg Hunt in his World War II little book of poems Reminiscences of Moresby, in which he promised the reader “20 minutes of good reading”. Photo: John Thistleton.

For the first six months after returning from fighting in the jungles of New Guinea, Reg Hunt could not bear to sleep inside. He slept under pine trees at the family’s farm, Glen View, at Parkesbourne, south of Goulburn.

Enlisting in the army in 1941 during World War II, Reg came under sniper fire and bombing, and suffered from dengue fever. Sustaining him through the ordeal, which included watching his best mate being shot dead, was the poetry he wrote in a tiny booklet.

“Once they thought they had us beaten, but the Aussies never run,” he wrote in an early poem.

“So we are going now to meet them, we intend to give them hell,

“For we are Aussie he-men and we’ll make those blighters yell.”

His poems tell the story of his grim war, and a lovesick soldier missing his girlfriend at home.

“I am writing you a letter to tell you of my love.

“And now I know you better, I just think that you’re a dove.

“Your eyes they shine like diamonds

“Your teeth they shine like pearls

“Your life is red as roses, you’re sure one of my girls.”

Reg’s booklet did not come to light until many years after the war when he revealed his poems to his daughter, Lorraine, one of six children. She does not know who the girlfriend was, other than she may have been named Lorna.

For years, Reg said little about the war, then told Lorraine, who worked alongside him in his nursery, that one of his mates down the road at Parkesbourne, Charlie Murphy, served with him and was suddenly shot dead next to him one early morning.

The Australians had been trekking up a ravine and had come to a point at night where they could go no further. As it happened, the Japanese were on a facing incline.

“They stayed the night and when they woke up, realised they were on a little ledge. Charlie got up, stretched his arms out and was gone,” Lorraine said, recounting her father’s story.

“Dad said if you were smoking, you could never light three cigarettes with the one match.”

Seeing the glow of the match, the enemy would ready their rifle on the first cigarette, take aim at the second cigarette and fire at the third.

Food was still scarce in Australia when Reg Hunt was discharged in 1944, aged 23. As a condition of his being allowed home, the army had asked his family to provide 1000 chooks for the war effort, according to his daughter Lorraine. Photo: Hunt family collection.

Reg was ill, lying on a stretcher outside a hospital, when air-raid sirens sounded. Two soldiers grabbed either end of the stretcher and rolled him into a crater to protect him from the shelling.

A close family acquaintance, Lillian Apps, pressed a sprig of wattle that she sent to him. He passed it down a line of soldiers, some so homesick they cried when they smelled and touched it.

Reg answered an enormous number of letters from his family, aunts, uncles and friends, who kept him updated on crops, the weather, livestock and the arrival of six puppies. On Christmas Day 1942, he wrote the troops were issued with hampers containing cake, pudding, chocolate, dried fruit, etc. For Christmas dinner, he ate turkey and seasoning, potatoes, carrots, and plum pudding and custard.

After the war, Reg kept his booklet, Reminiscences of Moresby, in a dressing table drawer until his death in 1989.

“Of course, when I got the phone call from Mum to say he had died, I got in the car and went out there, straight for that book,” Lorraine said. “Nobody knew about it.”

The booklet is well worn, but the heartfelt sentiments on its few pages remain timeless.