Goulburn Court House was built to display the power and might of the British Empire, law and order and stability for commerce, and commerce for investment and immigration, says sketch artist Steve Ayling. Photo: David Carmichael, (DTC Photography).

Buildings as beautiful as Goulburn Court House keep Steve Ayling sketching and studying them and urging all around him to understand architectural language so they too can comprehend their timeless appeal.

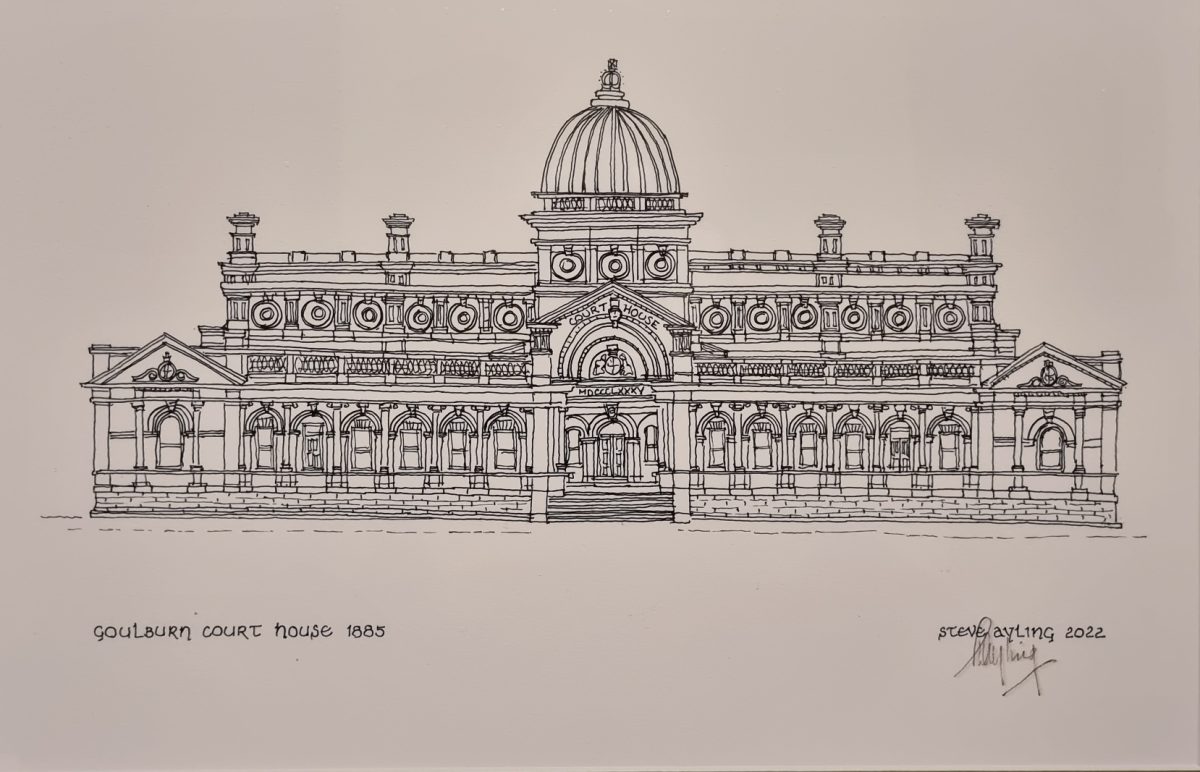

Numerous people have told the gifted sketch artist the same urban myth about Goulburn Court House. It was built in Goulburn by mistake, they say, as he sells his sketches at the Rotary Markets in front of the magnificent 1885 building. It was meant for Bombay or somewhere in India, they claim.

Steve has found no evidence to support this. He has studied the court house in detail for an assignment while completing an online Oxford University course, ‘Learning to Look at Western architecture‘. He notes prolific colonial architect James Barnet who designed more than 300 buildings in NSW deployed all the tools in his architect’s toolbox to create this impressive building specifically for Goulburn.

Steve traces the origins of those tools right back to Roman times when Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, who served in the Roman army, later became an architect who studied proportions. (Vitruvius’ description of the proportions of a well shaped man centuries later inspired Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.)

“Vitruvius said the principles of design of any building are firstly strength, that it’s solid and going to last; functional use, that is it’s designed for a purpose and should be efficient in what it delivers; and the third one, which is the most important one, beauty,” Steve said. “Formal buildings should be pleasing to the eye because of their proportions.”

Vitruvius’ 10 chapters on Roman architecture were lost for many dark centuries, then rediscovered and translated, helping to inform the Renaissance.

“In the Renaissance, Michelangelo and all the leading artists started to wonder why the Romans did such beautiful work; they started to puzzle on to the intellectual approach of it, fuelled by Vitruvius,” Steve said.

“In the Renaissance the term ‘neo classical’ came about, that is they didn’t replicate exactly what the Romans did, but took the bits and pieces the Romans used and shuffled the pack,” Steve said.

Steve Ayling encourages people to think about the architecture of significant buildings like the Goulburn Court House and understand the architectural language that the architect, the builders and owners wanted to convey.

Their work caught the eye of the British upper class while on their grand tours of Italy. It became fashionable to understand the Roman architecture and replicate it elsewhere throughout the empire.

“At the height of the British Empire, they understood the need for grand buildings, to impress upon ordinary people the power of the Crown, the wealth and the might and they started turning them out,” Steve said.

So today, the Neo-Classical design of the court house also cleverly incorporates a wealth of earlier designs.

“In this beautiful building is the hand of the ancient Greeks, the hand of the ancient Romans, and the hand of the Renaissance as characterised by the octagon drum on which the dome sits,” he said. “They had worked out the engineering for it.”

Explaining the proliferation of round arches in the court house, Steve said they were first invented by the Romans, not on a whim but for superior weight distribution as they made taller and taller buildings.

At the court house gates, the ancient Greek influence is evident in the triglyphs – three vertical carved bands signifying the old wooden beams supporting the roof of temples. Triglyphs are everywhere on the court house’s exterior. Photo: John Thistleton.

“All of their long aqueducts have round arches; all of their tall buildings have round arches,” he said.

The Romans made triumphant arches as a visible display of their power and raised their buildings on a base to give it presence. This explains why the court house stands at an imposing level.

While the British borrowed extensively from the Romans and Renaissance architects, they put their own touches on the court house, including the keystones on the top of each of the arches.

“In their English country estate, it became fashionable to have balustrades,” Steve said. “The Romans didn’t put balustrades on things. The balustrade was one of the English things because in the English stately homes, one would have tea on one’s balcony with an ornamental balustrade around it.”

One of the many sketches Steve Ayling has done of Goulburn Court House. Photo: Steve Ayling.

Steve said the British couldn’t help themselves but adorn the entrance with Queen Victoria looking out on a keystone at the top of an arch, the British Lion below on another arch and with great magnificence the coat of arms, with unicorn and lion within beautiful casting work.

So pleasing to the eye today, the origins of the court house’s beauty are no accident and for that we can thank the earliest artists and architects who discovered and rediscovered there is harmony in proportions.