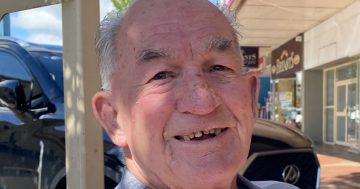

Boilermaker Brian Mills has worked with steel across Goulburn for more than 60 years. Photo: Supplied.

Brian Mills was born to bend steel. One of Australia’s oldest boilermakers still on the tools, Brian has bolted, belted, forged and welded steel across much of Goulburn’s industrial landscape for more than six decades.

The 82-year-old has seen manufacturing rise and fall, from the cotton spinning and weaving machines in the Pacific Chenille Craft factory, to processing plants at Goulburn Wool Scour, and heating, cooling and cooking at Kenmore Hospital.

All have closed. Brian endures.

From bakers to bootmakers, he has helped them all. He has seen Woodlawn mine near Tarago open, go underground, close and reopen again. When there was such a thing as the federal government’s Postmaster-General’s Department running communications, Brian repaired their big dozers as they cleared land for a coaxial cable.

He has learned several trades at Goulburn Engineering, where he began working in January, 1954. Rob Wallace, who founded the business about eight years earlier, called his mate, Ross Banwell – a woodwork teacher at Goulburn High School – for a recommendation for a new apprentice. Ross then consulted another mate, Charlie Everitt, a tradesman who taught metalwork at the school. They settled on a young Brian Mills.

Jobs were everywhere. Aged 16 at the time, Brian had two prospects for carpentry, one with plumber Sam McNaught, and one with the railway. He had also checked out the police force with a detective, Bruce Catts. However, a spark ignited within Brian in Rob’s flat-strap workshop.

“Anything in steel is my cup of tea,” he says.

Soon Brian was teamed up with Jeff Ison, who was the workshop’s first apprentice. They travelled together to farms where they built gates and stock crates. They welded and bolted and shaped conveyor belts, platforms, gantries, trolleys and cages all around town.

“He was older than me,” says Brian. “We sort of grew up together. We married the (Kinane) sisters – Jeff married Judy and I married Jan.”

Rob Wallace (left) and Brian Mills (right) have worked together since 1954. Photo: Supplied.

The council’s garbage trucks would be brought in for repairs, the floors having rotted out, patched and needing patching again. He uncovered rats and mice, long dead and smelling worse than old cabbage.

Customers grew to depend on him, coming in to the workshop with one question: “Where’s Brian?”

Keith “Trapper” Woodman of Trapper’s Bakery in south Goulburn calls him Uncle Brian.

“He gets out his piece of chalk and draws what I need on a board and rings me when it’s made,” says Trapper. “I have amazing toolboxes in all my farm vehicles that he has made. He has done a lot of behind-the-scenes work at the bakery.”

Brian was forging steel one day when a retired blacksmith, Bunny Lawson, came by. “He was a great old chap,” he says. “I was still a boy and he taught me how to repair plough shears and crowbar points. I still have my original anvil.”

Also handy are his original pipe wrenches, spanners, chisels and screwdrivers.

He has a sharp eye for a straight line, an asset where the slim margin for error is a millimetre or two. That precision also emerges on the weekend when he putts on the golf green or is at home in the garden clipping his privet hedge out the front in Audubon Crescent.

Neighbour Lindsay Cosgrove shouts: “I’ll be over to check that with the spirit level, mate.”

Brian has been off work during the COVID-19 lockdown. There’s purpose in his hour-long walks along the river. He is currently undergoing chemotherapy, having overcome a health setback a decade ago. Returning to the workshop and his workmates keeps him moving.

“I love what I do, and they’re a good bunch of fellows,” says Brian.

The Australian BHP steel he uses is a bit like him when under pressure. Unlike imported steel, it doesn’t buckle.

Original Article published by John Thistleton on The RiotACT.