Elizabeth Walton of Mystery Bay, last week during a break in fire activity. Photo: Supplied.

Mystery Bay is a small beachside community surrounded on three sides by bush, lush with mature spotted gums, with one small access road.

Last week the community was threatened by the Badja Forest Fire and, after evacuating at short notice, resident Elizabeth Walton spent the week in the Narooma evacuation centre, along with 4,000 others, as ash rained down and night and day became indistinguishable.

“The power was out at the evacuation centre. The people in charge received updates on the emergency by queuing up to use a payphone. For days on end, we didn’t know what had burned or if our homes were safe,” Elizabeth says.

With weather predictions for high fire danger today, after a few days at home, she will head back to the evacuation centre.

“Those of us from Tilba and Mystery Bay were told our homes would not be there when we got back. Something inside me broke hearing that but miraculously, the fire didn’t reach us.”

Despite being terrified, sharing three toilets with 2,000 women for a week and being exposed to ash and debris which exacerbated her asthma, Elizabeth feels that the evacuation centre is the safest place today.

“We don’t want to wake up at 4:00 am in a panic and have to evacuate,” she says. “Those fires are still there. Bega Valley Council recommended that anyone living within two blocks of the bush should move to a safer area and I think that’s wise.”

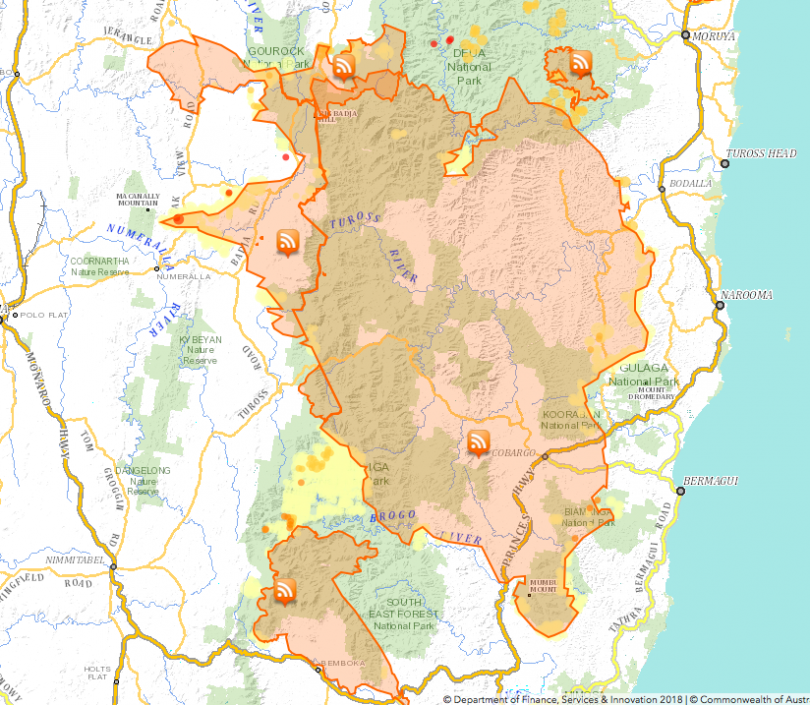

Looking at a map of where the fires travelled made Elizabeth aware of “how easterlies work”.

“The fire traces the coastline, you can see that if the wind swings around – off we go.”

A map of where the Bajer Forest spread last week. Photo: Supplied.

Reflecting on her week as an evacuee, Elizabeth recalls the one vet being constantly busy sedating cats, the local chemist working by candlelight to administer urgent medications, the Narooma golf club feeding the entire crowd one night on two-minute noodles and a lady who asked where the vegan queue was.

“The centre had a couple of Rotary and Lion’s vans cooking and distributing food and the lady in the van said ‘this is an emergency, there is no vegan option’. It is good that we are all going through this so we can understand what refugees are living through for years on end.”

She remembers members of the NSW Police arriving to help on day five and “I wanted to hug them to say thanks but felt fearful of engulfing them with a sea of swallowed emotion”.

Ahead of last Saturday’s predictions, evacuees were told to be prepared to jump into the ocean.

“We found a boogie-board abandoned by the garbage bins by a tourist and went down to the beach the day before to teach our dog to swim. The sea was full of floating gas tanks in case they exploded,” Elizabeth says.

Mystery Bay locals brought tractors to the beach to dig trenches to hide in on New Year’s Eve. Photo: Supplied.

Elizabeth considers herself lucky and says that spending a week sleeping in the car and not showering wasn’t the worst thing – what she’s really afraid about is the future.

“My partner and I have always advocated living simply. We have a food forest on our property and we are music teachers, we really want to boil life down to growing and eating food and connecting through music,” she explains.

The expectation to be able to live a certain lifestyle, earning money and consuming indefinitely, is part of the reason so many evacuees suddenly had their lifestyle temporarily stripped from them last week, Elizabeth believes.

Climate change and an outdated logging industry are also factors, she says.

“It’s past time to transition to a different industry than timber – our region was back burned in autumn. In reality, it’s mostly industrial clean up after state forest logging operations. Most of the trees are taken to the Eden chip mill to export overseas and now the mill has mountains of wood chips on fire.”

If clearing post-logging debris and back burning worked, Elizbeth believes, the town of Mogo wouldn’t have been affected by the fire.

Elizabeth’s life, along with thousands of others, is changed for the foreseeable future.

“My partner and I are musicians but for now, there are no more gigs. We prefer it that way – we have no voices left to sing, there is little left to give.”