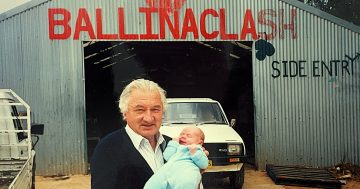

Father-of-three Dr Clive Cawthorne with two of his grandchildren. After extensive experience as a family GP he is now advocating for changes to get more doctors working at an earlier age. Photo: Cawthorne family.

Australia’s ongoing shortage of doctors persists despite twice the number of medical schools and more than three times the number of students learning medicine over the past 20 years.

A long-serving, widely experienced doctor from Crookwell believes he has some solutions.

After spending much of his medical career in country towns, Dr Clive Cawthorne has taken a closer look at why the country is not keeping up with the demand for GP services.

At age 81, he can reflect on a career which began in London’s prestigious Guys Hospital, and his open, inquiring mind that led him to Australia, Tasmania and outback to Bourke, where he discovered women had to travel four hours to Dubbo to have their babies delivered. The young mothers needed to spend two to three weeks there.

“Is this right especially for the mother who already has children at home?” he asked.

That experience in particular is driving his research and advocacy for more available doctors.

Now a farmer at Crookwell, having recently retired from being a GP after more than 50 years, Dr Cawthorne has sifted through Census data, medical statistics and training programs to understand the root causes of the shortage.

He has found Australia’s medical workforce has changed rapidly over the past 20 years.

From 1995 to 2022, when medical schools doubled from 10 to 23, the number of students starting medicine rose from about 1250 to 4192.

Over the same period Australia’s population grew from 18 million to 26 million, adding to the demand for more GPs.

But statistics show although the supply of GPs has increased there are not enough general practitioners working long enough in their careers.

More than two thirds of the students are over 30 by the time they become doctors. And a high proportion of them are females (57 per cent) who work fewer clinical hours than their male colleagues.

By the time they are 30, many of the new doctors have children, mortgages and other responsibilities.

“I believe that we need to train younger people so they are doctors in their early 20s who can go to hospital jobs where they can live in and get a wide range of medical skills and then they can provide a longer career in service whether GPs or specialists,” he said.

From Kent in England, Dr Cawthorne became a doctor at age 23.

A few years later he set off with a friend on a Honda CD175cc motorbike and made his way to Australia, arriving in 1971 after an epic travelling adventure.

He worked as a resident doctor in Perth hospitals for 15 months, then left Western Australia for Tasmania for 20 years, where he worked at hospitals in Launceston. Later he transferred to the small town of Scottsdale in northeast Tasmania where he worked as a GP and met his future wife Meredith, who was visiting from Bowral.

He has also practised in the Southern Highlands, where he built a surgery at Hill End, Gunning and Crookwell.

He said training more students via direct undergraduate entry would mean doctors qualified younger, around 23 rather than 30 years of age.

“Younger graduates are more flexible for hospital-based rotations, more likely to spend longer overall careers in medicine, and will normally incur only one cycle of higher education fees,” he said.

“This increases their lifetime workforce contribution, improves training availability for essential procedural skills, and supports building sustainable teams in regional and rural areas,” he said.

He believes governments need to work towards maximising doctors’ years of full-time service to the public.

Dr Cawthorne said advantages of younger qualified doctors significantly outweighed the disadvantages of a delayed postgraduate entry into medicine.

Entrants who qualified around age 30 reduced their potential working years and increased the need for replacement doctors. They had higher training costs, often two rounds of higher education fees.

And they weren’t as mobile as their younger colleagues because of family and mortgage commitments. They were either unable or unlikely to undertake extended or remote hospital training posts.

There was also the risk of gaps in their skills. “Mature-entry cohorts may have less opportunity or time to obtain high-volume hands-on experience in normal deliveries and other procedures as undergraduates historically did,” Dr Cawthorne said. (His initial training included delivering 20 babies.)

Having worked in rural communities, he believes it’s important to draw medical students from country towns, where they are more likely to stay and practise once they are qualified.