National library curator Guy Hansen with David Pope’s muscular cartooning kangaroo at the entry to Inked. Photo: Supplied.

One of the great media pleasures has to be a perfectly drawn cartoon, waspishly targeting the pomposity or ridiculousness of the day and plunging a hatpin through the political bubble of self-importance.

And as it turns out, there’s nothing new in any of this: the National Library has just opened Inked, an exhibition that traces more than two centuries of Australian cartooning, “since the First Fleet bumbled its way into an unsuitable harbour”.

Indeed, one of the first things you’ll see in the show is a wicked caricature of King George IV, perched on a wine barrel as he’s shipped off to Botany Bay as a punishment for dissolute behaviour. Governor Bligh is being hauled from under his bed by the NSW Corps nearby, while from the next room, animated Leunigs and the unmistakable 3D figure of Sir John Kerr beckons in his top hat.

Curator Guy Hansen says the Libray holds no less than 14,000 cartoons, some of them a complete mystery to the casual viewer as the context has been lost. But the 135 cartoons selected for this show are as sharp, brilliant and pointed as anything you’ll find today, telling stories about the country, the events and the people.

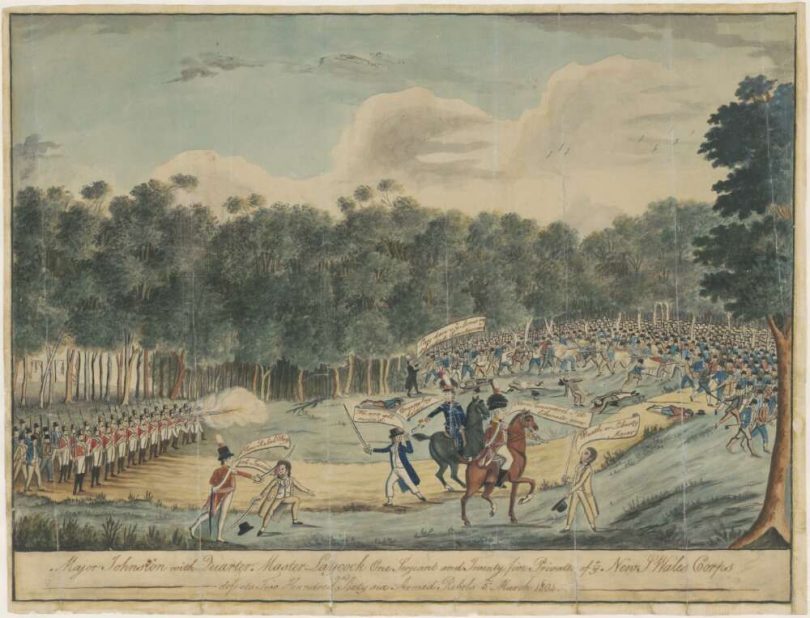

The earliest cartoon completed in Australia shows the 1804 Castle Hill convict rebellion.

If there’s a theme, it’s that Australian cartoonists have always had what Hansen calls “a disrespectful approach to politicians”, although the artist’s role has evolved from that of illustrator and gag artists to social commentators.

“They evolved and became social commentators in their own right,” Hansen says. “By the time you get to Les Tanner and Bruce Petty you’ve got fully fledged social commentators putting forward their own political ideas, independent of the newspaper they’re working for – Bruce Petty worked for Murdoch and carved out an independent voice.

“Today’s editorial cartoonists assume they have that voice, but earlier on in our history, they did what the editor told them to do.”

There’s a great photo at the front of the exhibition that shows the Black and White Artists’ Society in full swing sometime mid-century, replete with luxuriant facial hair and the distinct air of having indulged in some cleansing ales. “Yes, it was a boys’ club for a long time,” Hansen says ruefully. “That was Australian society. You can’t shy away from blokes with moustaches who all look like they’ve had a few beers.”

An artists’ smock presented to the great Stan Cross hangs nearby, and anyone who read a comic in mid-century Australia will recognise many of the drawing styles. There’s Jim Russell, for example, who drew the Potts comics for 62 years. Cross’s own legendary cartoon showing two blokes dangling from a girder and the caption “For Gorsakes Stop Laughing: This Is Serious!” hangs, in the original, nearby.

Hansen says that back then, there were thousands of black and white artists working on newspapers. Paid very well by the standards of the day, they were larger-than-life personalities. These days the role is more modest as the consolidation of media and the rise of the digital age means that cartoons must be produced more and more quickly as the appetite for immediate content grows inexorably.

Hansen himself is a “huge fan” of Bruce Petty and his wildly evocative, fantastic vision of the world, calling him “a giant among cartoonists”, but also enjoys Ron Tandberg’s starkly simple work and that of Judy Horacek and Cathy Wilcox.

“Petty tries to explain the complexity of the world with magical images, while Tandberg is like an Exocet missile who will knock you flat with his observations,” he says.

Canberra’s own cartoonists are well represented, from Pryor to Pope, whose illustration of a heavily tattooed kangaroo flexing its muscles fronts the show.

“My favourite metaphor is that the cartoons are like fossils in a cliff face. You can excavate and find some reminders of the past,” Hansen says. “They’re evidence of the past visual culture, they remind you of what happened and they can all tell you some stories and spark memories.”

Original Article published by Genevieve Jacobs on The RiotACT.